Bruce Mau Is Designing Away Our Worries

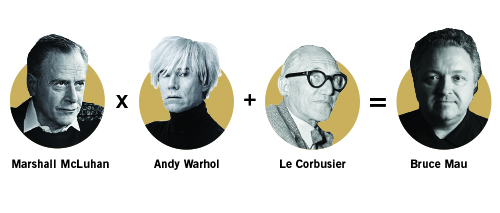

Though “creative” can be an obtuse job title, in Bruce Mau’s case it’s the only word that really does his full spectrum of work justice. After starting his career in Toronto as a graphic designer, he’s gone on to serve as a magazine editor, an architecture professor, an artist, and a curator.

Now based in Chicago, Mau spends his days as co-director of the Massive Change Network, a consulting agency that counts Coca-Cola as a client. With a side gig as chief design officer of trade show management firm Freeman, he’s no stranger to planning splashy events, either. So when the team behind Toronto’s Design Exchange museum set out to launch a 10-day design biennale this fall, they knew who to turn to for vision. Taking place from September 28 to October 8 in the city’s former Unilever soap factory, the resulting festival — dubbed the Expo for Design Innovation and Technology, or EDIT — showcases recent innovations in housing, health care, education, and food. Mau’s contribution is a feature exhibition that juxtaposes photojournalist Paolo Pellegrin’s snaps of global conflicts with more upbeat evidence of our recent successes as a society. If that sounds optimistic, well, meet Bruce Mau.

I’m reaching you in L.A. When was the last time you considered design today?

The shower in my hotel this morning was too small. I spend a lot of time in hotels, where your experience is largely a reflection of the quality of the design. And the shower, for some reason, is consistently bad. In too many of them, the curtain touches you while you’re showering. The Westin introduced a curved shower rod, which solves the problem by drawing the curtain farther away. But there are still millions of hotel rooms that haven’t implemented it.

I prefer a glassed-in shower myself, but those can be cramped too. To shift to the positive, then, what’s a recent design that has you particularly excited?

The best example is the Tesla. It just offers a profoundly different experience than other cars. Shortly after we bought ours a few years ago, we received a notification asking us to plug it in that evening for an update. Another Tesla had hit some debris that damaged the car’s battery and started a fire. It was only one of 200,000-odd car fires that year, but Tesla identified a way to prevent it from happening again. They raised the suspension to create more ground clearance — all through an update in the middle of the night, with no mechanics involved.

What’s your take-away as a designer from the vision you see at Tesla?

They have a design thinking process that’s about questioning everything. The old style of thinking was devising discrete solutions to discrete problems. That meant never thinking about climate change while designing a car. But just aiming to create a more beautiful, more advanced object will never solve larger ecological issues.

Contrast that with what Elon Musk is doing. At EDIT, we’ll be displaying his new solar roofing product. Keep in mind that when Tesla first acquired solar panel installer SolarCity, their stock price went down. Investors wondered, “Why is my car company up on my roof?” But Tesla is not a car company. They’re envisioning a future where one day the energy you capture in your home can be used to power your car. It’s a full energy-movement ecosystem.

With EDIT, you push back against a narrative of doom and gloom by celebrating success stories. How do you feel about the news you read each day?

We’re practically not getting any good news. When people read the paper today, they’re afraid. The New York Times scares the living daylights out of you, which is a shame, because a reader’s natural response in that circumstance is to protect themselves. They become defensive. They close the borders and lock the door.

But when people see that others are engaged and investing in the future, they want to be involved. When people launch a campaign to build a new museum, it’s exciting and there’s a sense that there’s a community someone could be a part of.

“Let’s design society so that even more people can participate, because that’s how we’re going to solve the next round of problems.”

Is there a risk to presenting such a sunny outlook?

Well, it’s analytical. I’m a designer, so I start with analysis. It’s fact-based optimism. The truth is that we are facing “success” problems. Our problems today are because we succeeded in fighting back hunger and disease. Right now, the Institute of Food Technologists think tank is trying to figure out how to feed 10 billion people. But if we’d failed more, we’d only be a billion people, which shows what we’re capable of.

It’s the best time in human history to be alive and working, by a radical long shot. In Roman times, we were killing kids for entertainment. At different times in history, women were property and vast numbers of people were slaves. For most, the life expectancy was 30 years. So for the vast majority, the past was much worse than today, even with today’s disparity. It’s still not evenly distributed, but there are legions of people working on distributing it better. So let’s design society so that even more people can participate, because that’s how we’re going to solve the next round of problems.

When people hear “design,” they tend to think of graphic designers or architects, but you’re using the word as a very broad term. And EDIT looks at innovations made by doctors and chefs. Why extend the focus of the show beyond just the usual suspects?

We use the word “design” colloquially more intelligently than we do profes- sionally. There are lots of places that the word “design” now belongs where it still isn’t being said. In business schools, for instance. We don’t need MBAs anymore. We need MBDs. Administration was the challenge when a company was just making one thing and had to scale it. Now, businesses should be embracing design thinking and constantly reconsidering their product.

EDIT is taking place in a gritty former soap factory. Designers have a reputation for liking things very clean — spare, sophisticated, and simple. What’s the benefit here of embracing some mess?

Personally, I’ve never strived for a clean notion of design. I don’t think of design as pristine, fancy things. I know that a lot of people do, but my design is taking on the toughest challenges that we face.

In line with that, this location demonstrates the power of transformation. The shift from an industrial past to an information-focused future — which is what’s driving this whole new culture of design — is profound. We have millions of industrial buildings all over America and the world that we’re going to need to repurpose soon. An old soap factory is a great place to have a conversation about that.

One of your many jobs now is working for Freeman, which plans events. What’s changed about how you reach people at an expo or a trade show, in a digital age?

The industry event once had a lock on the dissemination of up-to-date information. It was enough to just bring in a table, set a new object on it, and run a demonstration. But that’s no longer the case. Almost everything at an event is now available online.

Now, events must offer inspiration, possibility, and the chance to connect with like-minded people. We’re using data to understand what your goals are and to help you reach your goals. We also customize a show in real time. That might mean moving someone from a meeting room to a mainstage based on the attention they’re getting online. That sort of flexibility is important.

At the announcement event for EDIT, you compared it to Canada’s Expo 67 centennial fair in Montreal. How did that event influence your career?

It blew my mind. At the time, I was eight. I was living in Northern Ontario outside of a mining town, and I had never been to a city, but I saw footage on TV filmed from a helicopter that was flying around the grounds.

The concept of design just wasn’t part of my life on the farm before that, but it became what I wanted to do. I’ve been collecting books and brochures from ’67 ever since. And even though EDIT is a small percentage of what that was, our primary responsibility is still to inspire. That’s the real test of our work. To inspire people, you have to be brave enough to show them what’s possible.