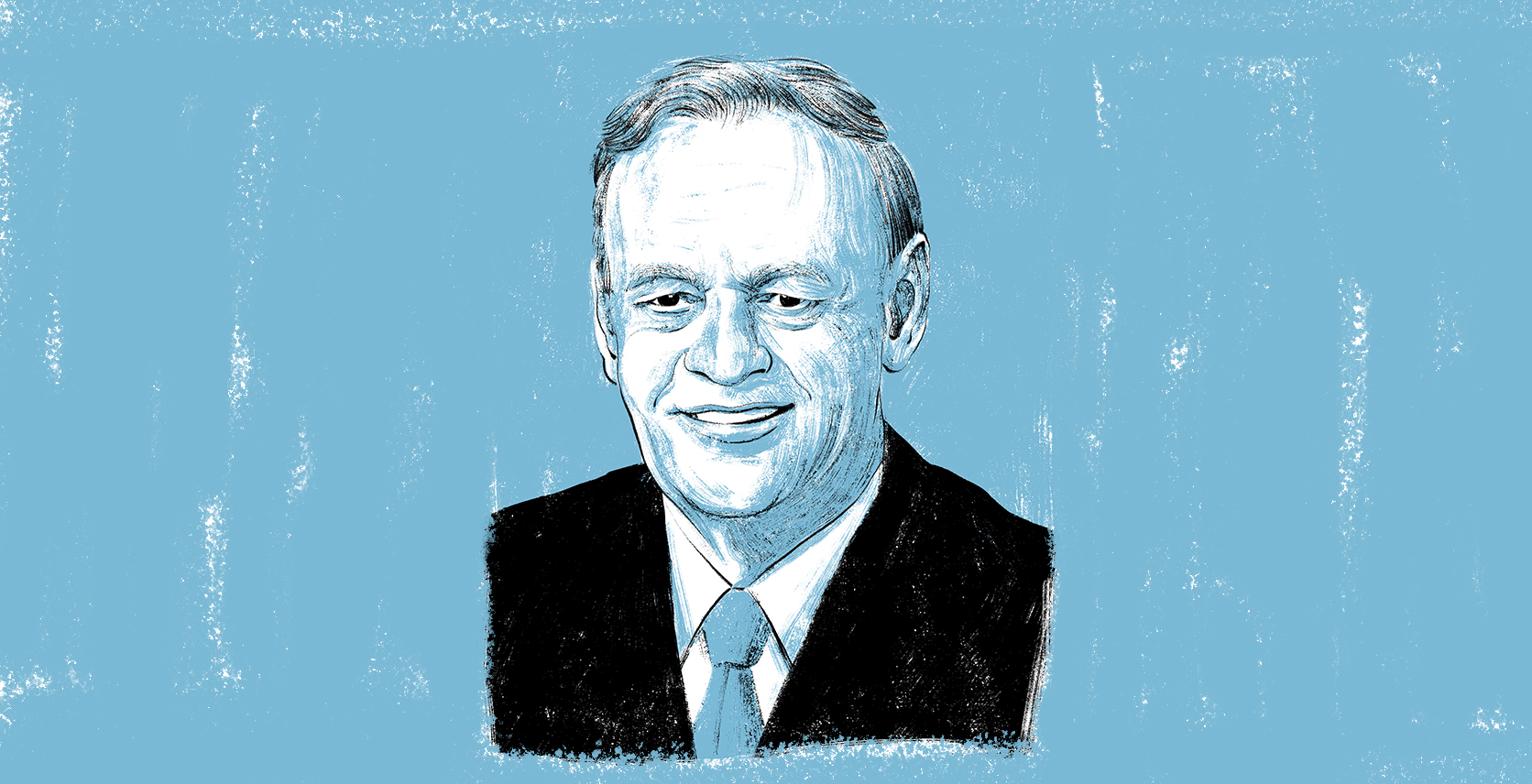

Jean Chrétien on the State of Canada, Russian Relations, and Staying Friends with George Bush

Throughout a country’s history, there are forks in the road. Take enough of them, and the nation might be unrecognizable a generation later. It’s rare for anyone to have stood at as many forks as Jean Chrétien has. During his decade as prime minister, Chrétien made international headlines when he declined to join the American invasion of Iraq; as justice minister, he fought against Quebec’s separation from Canada and helped to establish a new constitution for the country. Now, at 84, he reflects on more than 50 years in the public service — during which time he has competed in a vodka-fuelled swim race in Siberia, endured international uproar over continental shelves, and executed a daring hostage rescue. In his new book My Stories, My Time, Chrétien chronicles the joys and frustrations of the public service, what keeps him going, and why — after all these years — he’s still a happy man.

I’m struck by two observations in your book: that periods of quiet reflection and humour seem to be disappearing from politics. What do we lose?

You need time to reflect, because you cannot go go go. Sometimes, you need to put things into perspective. To be quiet — at the lake, walking in the bush — allows you to do that. If you’re always in meetings and briefings, meeting the press and talking and so on, it’s good. But for me, it was important I find some time to reflect. And I did. I like to say, “Truth cold is difficult to swallow. Wrapped in humour, it’s easier to swallow.”

Did you find it helped to defuse tense situations?

It helped me a lot. You can defuse crises when things get tense. A little bit of humour creates a better atmosphere.

There’s a loneliness associated with being the head of government. Did you often feel that weight?

My wife is close to me and I have kids, so I never felt that I was lonely. You don’t have the time to, for example, have two or three friends over for a dinner. There’s no time at all to play cards. The schedule is too demanding. Personal friendships don’t expand. People that you’re with most of the time…You have a relationship between boss and employees. That’s not the same type of friendship you have with a buddy playing cards every weekend.

Is it hard to strike up friendships after you leave office?

I’m used to that type of life. At my age, many of my former friends from college, they’re gone now. They’re going one by one. I’m lucky. I’m in good shape and I’m still working. I believe working is helping, because my father used to say, “Move or rust.” I believe if the brain is working, the body follows.

You reserve your highest praise for your wife of more than 60 years, Aline, calling her your Rock of Gibraltar. What’s your secret?

I used to say, jokingly, “You have to make water into wine, and if it’s not working, you give her the glass of wine and you drink the glass of water.” She was 16 when I met her and I was 18, so we know each other very well and we never had a problem in our marriage. We faced, like any family, difficult times. But we help each other and we’ve been happy and are still happy to be together.

You spend time in your book sketching out a vision of Canada as an idea — not just a geographic location — and the values that define it. Are there values we’re still failing to fully realize as a country?

It is a never-ending journey to build a country. Values develop over time and societies change. If you’re open-minded and tolerant, and if you’re generous and willing to share, these are values that are always good, even with change. They are basic to have a proper life.

“We’re a prosperous country. On a daily basis, always, we feel like it’s the end of the world. But when you put everything into perspective, we’ve made progress.”

You outline many of the challenges that Canada is facing. But the book still feels quite hopeful. What gives you hope?

Because I’m an optimistic person, I believe that humanity has made a lot of progress over the last 50 years. I don’t know why we will not keep progressing. Of course, there will be problems — there will always be problems. But when I look at where we were in 1963, when I got elected, and where we are today, we’re not the same country anymore. We have double our population, at least; we’re a prosperous country; we have all of the freedom we hope for. That’s why I’m hopeful. On a daily basis, always, we feel like it’s the end of the world. But when you put everything into perspective, we’ve made progress and I hope we keep making progress.

Have you always felt the centre — politically — was the best place to be?

Canada is the best centre in the world. When I was in politics, they’d ask me, “You’re a Liberal, Chretien?” But a liberal in the United States is a left-winger. In Europe, they’re a right-winger. They say, “What is Canada?” If the people of the left say you’re a right-winger and the people on the right say you’re a left-winger, you’re a good Canadian Liberal. When both complain, it’s because you’re right about it.

You’re very well-known in Canadian public life as being someone who was involved in the patriation of the constitution, the Clarity Act, and the Iraq War, but I was really surprised to see you talk about your time doubling the number of national parks in Canada.

I enjoyed doing it. And nobody knows this. But it was very exciting to do that. To be a minister of justice in front of a committee, for hours and hours replying to questions from members of parliament and senators, I’m telling you, it’s no fun. But a park is very concrete: like the one I made for my wife in the north [Auyuittuq National Park]. I consulted the minister of Indian affairs, who was Jean Chrétien. The minister of parks was Jean Chrétien. The minister of the North was Jean Chrétien. The three agreed!

You seem sure of Russian interference in the American elections — but at the same time, caution against an increasingly combative relationship with Russia as a solution. What is the best path forward for all countries?

If the Russians need money, they turn to Beijing. I’m sure the Russians and Chinese are very close now. That’s why I describe the discussion we have had about making Russia part of Europe. It would have been a very good move. But after I left and the other player left, nobody talked about it anymore. It would have made Europe much stronger, having all the resources of Russia, part of the common market. That would have been pretty powerful stuff. And they would have been obliged, as I wrote, to play by the book. I’m of the view that if Russia had been part of Europe, it would have been a much better situation today.

Is it too late?

It’s never too late to do the right thing. But the Americans love to see the Russians as an enemy.

You’ve remained friends with those who you publicly sparred with, including Jacques Chirac and George Bush. What’s the importance of personal friendships in diplomacy?

We’re all politicians after all. We have to be elected. And we know the tough life of being a politician, so we develop a necessary sympathy for the profession. This establishes links between politicians, even when they disagree sometimes on approaches. It isn’t easy to become prime minister or president of a country — you have to work hard. There are very few guys who can rise to the top.

You’re now a great-grandfather. What’s the personal legacy that you’d like to leave behind?

You have to work in life. I did work — a helluva lot. Serving is very satisfying. And I’ve been serving a helluva lot, too. I’m a happy man.