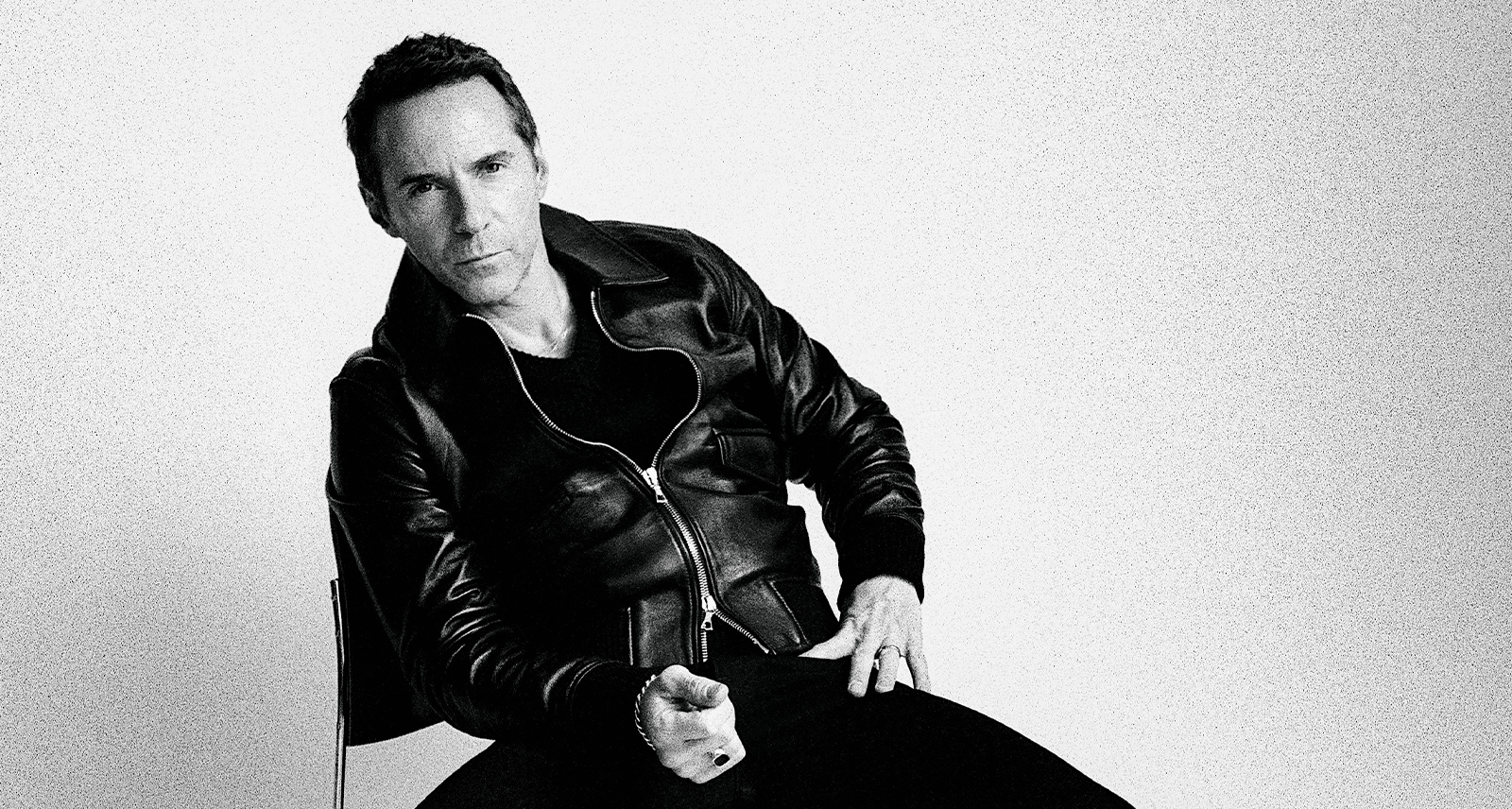

How Joe Beef Chef David McMillan Conquered Canada’s Food Scene — and His Own Demons

“Here, try this,” says David McMillan as he hands over a drink. The chef and co-founder of Montreal’s Joe Beef is standing in the kitchen of the cozy pied-àterre apartment he occupies the several days a week he’s not out in the country, fishing at his cottage. It’s located upstairs from the eponymous founding establishment in the Joe Beef empire, which has grown into a tight collection of four restaurants mostly located in Montreal’s Little Burgundy neighbourhood.

McMillan was once famous for his devotion to Burgundy vino (“I love red Burgundy so much I want to pour it into my eyes,” he proclaimed in his first cookbook), and his restaurants are now lauded for their adventurous selection of natural wines. So it’s a little surprising to see him presenting not a glass of something orange and unfiltered, but a tall boy of Carlsberg 0.0%.

Did David McMillan just offer me a near beer?

“They’re fucking delicious,” he says. It’s been a weird year for the Joe Beef family. With an acclaimed new restaurant, Mon Lapin, reviewed glowingly in the New York Times soon after it opened, a growing and unchallenged natural wine program, a thick new cookbook on the way, and a #3 spot on Canada’s 100 Best Restaurants 2018 list, the team is undeniably at the top of its game. But it’s been a challenging year — perhaps their most challenging since they opened on an almost-forgotten strip of dusty antique furniture stores in Montreal’s south-west in 2005.

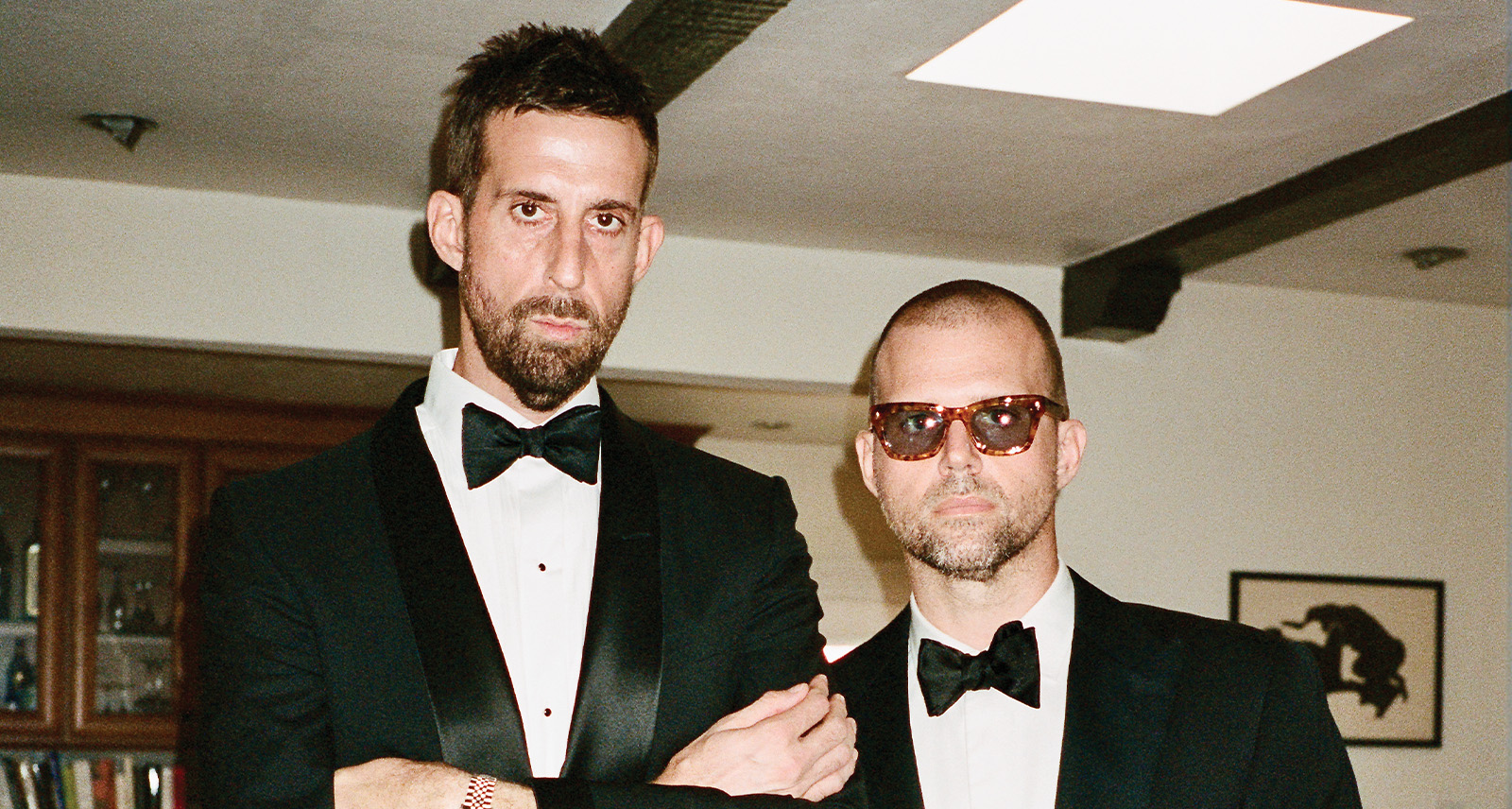

Back then, Joe Beef felt like an affront to the trendy Montreal supper-club culture, the lower Saint-Laurent fine dining spots where McMillan and his partner in crime, chef Frédéric Morin, toiled in the ’90s and early ’00s. Named after a legendary 19th-century Montreal tavern owner known for keeping live bears on the premises, the restaurant dispensed with all the finicky white-tablecloth frippery of the high-end eating experience. (“People walk through that door expecting Eleven Madison Park and they’re in a woodshed,” says Meredith Erickson, co-author of their books and one of the restaurant’s very first servers.) Menus and wine lists written on chalkboards. Decadent food with its roots in French market cuisine and French techniques, but stripped of pretense, with a sense of humour and adventure. Eel nuggets. Foie gras sandwiches — with the foie as the bread. All executed with absolute precision and panache.

Restaurant-goers take some of these things for granted today, but at the time, Joe Beef was a revelation. David Chang famously ate at the bar every night for a solid week when he took a vacation in town during the first few years of Momofuku Noodle Bar, and still calls it his favourite restaurant (he’s written the foreword to both of their books). When Anthony Bourdain befriended the two chefs (an easygoing friendship of late-night texts and cigarettes by the pool), and featured them on multiple episodes of his various shows, it felt like an anointment. Bourdain’s co-sign told the world what Montrealers already knew about Morin and McMillan: that they were the real deal — authentic and passionate chefs in a world of game-show food celebrities.

What Chang and Bourdain observed was that there was something special about the oxygen in the local atmosphere that kept Joe Beef going. “Montreal clientele is incredibly sophisticated,” McMillan says. “Our dining public is everything — that’s our advantage over New York City, over Chicago. We can do the food that we do because our dining public is super-receptive, adventurous, hyper-intelligent. It permits us to practise the art of cooking in a way that you can’t really do in Ontario or the rest of North America. What I mean by that is, I sell a lot of rabbit. I sell liver. Kidney. Ears. Tails. Other restaurants, tails and tripe and kidneys are on the menu to impress other visiting cooks. But my dining public eats it. I have 19-year-old girls who eat kidneys medium-rare. That’s not happening in Manhattan.”

That said, McMillan ruffled feathers a few years back when he proclaimed Toronto, a.k.a. the enemy down the 401, as Canada’s best food city. These days, he walks that back a bit: “I say a lot of things and a lot of nonsense. I spent a lot of time in Toronto over the last couple of years and I liked it. Toronto is a more cosmopolitan city than Montreal — it’s an American city for all practical purposes. There are a lot of offerings and a lot of very, very good restaurants — to say otherwise would be ignorant. But do they have the craft of cooking that we do? No. Is it difficult to drink natural wine in Toronto? Yes.”

Then again, as that Carlsberg 0.0% on the table attests, lately wine — natural or otherwise — hasn’t exactly been McMillan’s drink of choice.

•••

They could have gone big. Could have opened a Joe Beef Las Vegas, a Joe Beef Macau. You could have eaten a diminished version of their famous lobster spaghetti in airport departure lounges around the world. And the casinos and hotels did come calling. But instead, they played it close to the vest. They expanded, but didn’t leave their block, opening Liverpool House next door (Barack Obama and Justin Trudeau dined there together in 2017) and, more recently, Le Vin Papillon, an exquisite wine bar where the food is notably more vegetable-forward than at Joe Beef — which, despite its name, isn’t a steakhouse. They published The Art of Living According to Joe Beef, a combination cookbook and bon vivant bible that introduced the world to their unique sensibility.

“I’ve drank every day of my whole fucking career, and I’ve done drugs every second day. It’s been a fucking dark blotch. I remember very little of my career, and what I do remember is that I’ve been unhappy.”

Things, at least on the surface, seemed to be going swimmingly. But 2018 hit, and it hit hard. There were some victories: finishing a new book; opening that new restaurant. But on the heavier side of the ledger: the death of John Bil, an oysterman and close friend who helped the team open its very first restaurant — and who would later go on to open fish counter Honest Weight in Toronto — after a long fight with cancer; the shocking suicide of their good friend Anthony Bourdain, not long after the three had made a trip to Newfoundland together to film an episode of Parts Unknown.

And finally, a struggle with the addictions that defined both chefs’ professional lives. “Fred and I have had an appetite for destruction for a long time,” McMillan tells me. “I’ve been an addict. I’ve drank every day of my whole fucking career, and I’ve done drugs every second day. It’s been a fucking dark blotch. I remember very little of my career, and what I do remember is that I’ve been unhappy.”

Early in the year, McMillan’s staff organized an intervention for him. “They were watching me kill myself inside my restaurant,” he says. They persuaded him to go to rehab (“I got the extra treatment — the restaurant package”). And although recovery is always a work in progress, it seems to have unlocked something in McMillan, and he genuinely seems healthy, trim, and happy. “I thought I drank because I hated my life, hated the restaurant business. The fact is that I love the restaurant business. I love these companies, the people who work in them. I love natural wine. I love farming. I just got away from it because I indulged in drugs and alcohol and I was always depressed.”

•••

It’s impossible not to think of their friend Anthony Bourdain, a man who dealt with no small share of his own demons, drugs, and alcohol, when McMillan talks about his own recovery. Whether it was featuring the chefs on his shows, organizing dinners with them in Miami with Éric Ripert and Daniel Boulud, or just texting in the wee hours, their friendship seemed to be genuine, free of food- and show-business glad-handing and bullshit. “He was a very, very, very, very faithful and loyal guy,” Morin says. “When he passed away, I realized that year after year, we always spent a bunch of quality time with him, and our back and forth was always so exceptionally pleasant.”

But behind the scenes of the recent Newfoundland episode of Parts Unknown, where McMillan and Morin acted as sort-of tour guides for Bourdain, a black mood simmered. “I noticed a change in Newfoundland,” McMillan says. “It was a bit weird — it was different.” A few months later, they would get the call that their friend and champion had ended his life.

It’s no surprise that in the midst of all this darkness, both personal and global, they should put out a new book entitled Joe Beef: Surviving the Apocalypse. “I think that it’s amazing that we were able to write this book while this was all happening,” co-author Erickson tells me. “There were times while I was working on the book and David was in rehab that he’d use his 15 minutes to call me and talk about it. And we had some intense conversations.”

When they originally pitched it to their publishers, the apocalypse idea was a bit of a lark. The book shows you how to ride out the end of the world in style in your perfectly Joe Beef-ed cabin in the woods, feasting on crispy frog legs (“The main indication of the End Times is when it starts to rain frogs”), soothing sore throats with spruce cough drops, washing with their (beef-based) homemade soap. “It’s a shelter-from-the-storm kind of metaphor,” Morin says. “You’re in this cozy Hudson’s Bay blanket eating cabbage pie or whatever while the storm outside rages.” But the joke started to feel extremely real once they were mid-manuscript and 2016 rolled around. “We said, that’ll be funny, and then suddenly, Donald Trump gets elected.”

•••

In the end, the apocalypse metaphor is just one strand of a book that, like the first, intermingles food, culture, and life. There are ridiculously difficult recipes like Kidneys à la Monique, which requires the reader to sculpt a calf out of rock salt and stuff it with veal kidneys. But there’s also a recipe for all-dressed chips-flavoured butter. There are homemade bouillon cubes that you shape with a hash (the smokable kind) press. And interspersed with the recipes, chapters on the chefs’ obsessions: PBS programming, a regional potato chip-themed road trip, the Quebecois campground tradition of “Christmas in July.” Like everything they do, the book feels like something that nobody else could have produced.

But amid all of the soul-searching and the apocalyptic imaginings and the very real loss, there’s a sense of renewal at the Joe Beef empire. And that seems incarnated in Mon Lapin, the newcomer, helmed by chef Marc-Olivier Frappier and sommelier Vanya Filipovic. For one, it’s across town in Little Italy, their very first restaurant not situated in that same block where they originally took root. As at Le Vin Papillon, vegetables are front and centre (a recent menu featured a schnitzel made with squash in place of veal), but you can still order an exquisite skewer of lamb sweetbreads, while drinking natural wines from vineyards like Quebec’s Pinard et Filles, which produces a truly out-of-this-world orange. While still being part of the family, it feels like Morin and McMillan’s protégés have finally moved out of the house and across town into their first real apartment.

In a turbulent year, the establishment feels like a reaffirmation of the Joe Beef family’s importance not only to Canada’s food scene, but to the world. At once serious and playful, adventurous and rooted in tradition, decadent and thoughtful, Mon Lapin represents everything that Joe Beef’s admirers, famous or not, love about it.

Above all, it’s a reminder of just how grounded these master chefs seem, despite all their acclaim. “I know very successful chefs from the Food Network, from New York City, from Los Angeles. I don’t feel that they’re successful in a way, you know, because I swim in a lake four days out of seven,” McMillan says. “I don’t go fishing once a year; I go fishing fucking 65 times a year. I don’t pretend to go mushroom picking on Instagram; I go mushroom picking for real. I don’t pretend to grow vegetables; I grow a lot of vegetables.

“My success is to be here. My success is to go up north with my children. My success is to eat at my friends’ restaurants.” In other words, not just surviving, but thriving.