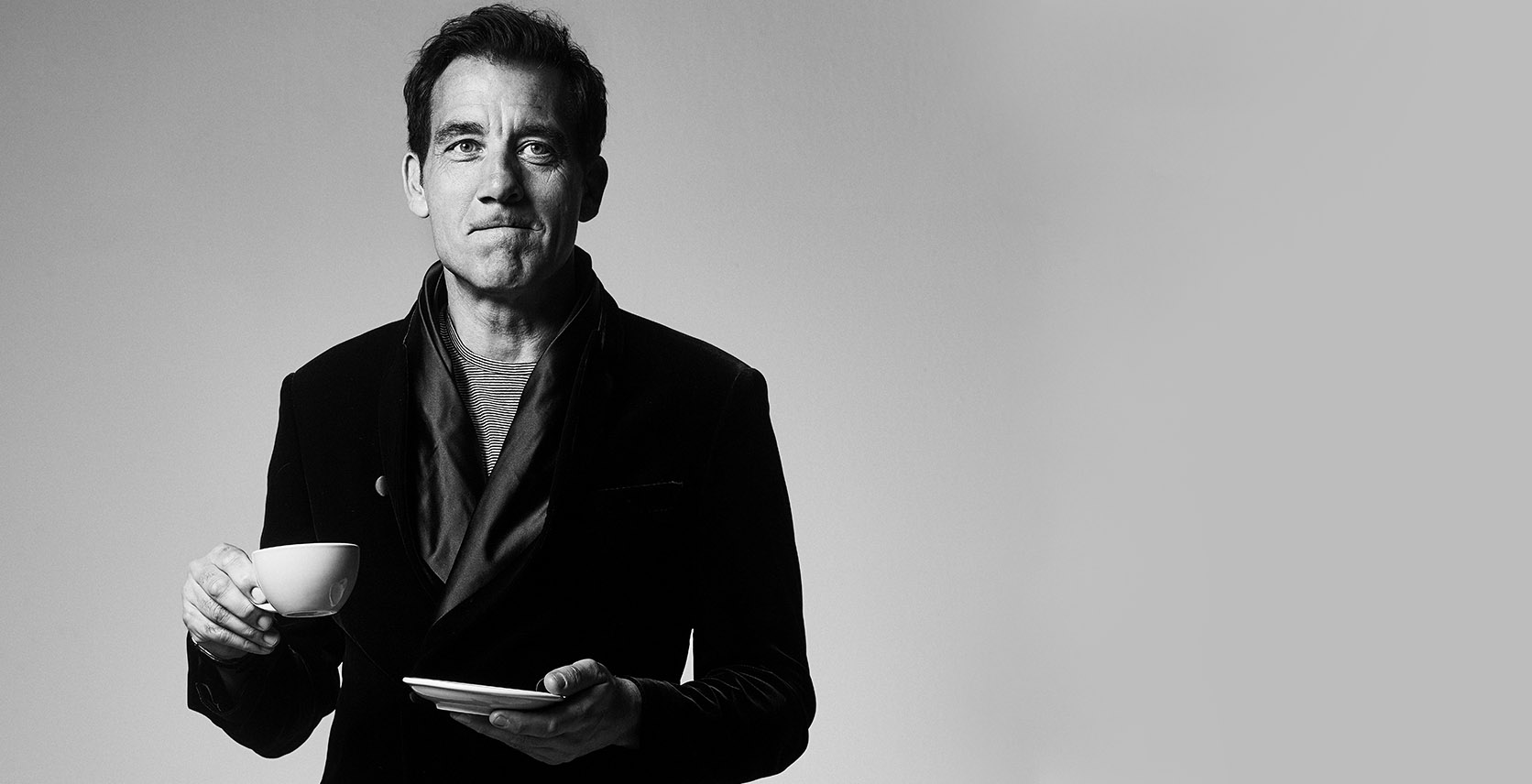

Clive Owen Doesn’t Need to Be Liked — Which Is What Makes Him So Likeable

A VERSION OF THIS STORY APPEARS IN SHARP: THE BOOK FOR MEN FALL/WINTER 2019, ON NEWSSTANDS NOW.

The best quote I’ve read about Clive Owen is from the British playwright Patrick Marber, who wrote Closer, the West End smash that eventually became the 2004 movie for which Owen was nominated for an Oscar. “Most of us go into showbiz in order to be admired and affirmed by complete strangers,” Marber said. “Clive doesn’t seem to have this terrible flaw. He has no sentimental need to be liked by the audience.”

Owen, who tends to speak low and slow, with a thoughtful intensity, lets out a long, low chuckle, like top-shelf-scotch sliding into a glass. “That’s definitely true,” he says to me on the phone from London, letting himself enjoy the laugh before snapping back to his usual cool composure. “I’ve always approached characters as, you know, I’m not there to charm you, but just have a look and see why that person functions like that. It’s not going to be easy, because good, complicated characters aren’t easy, but try to understand them.”

JACKET ($5,050) AND SHIRT ($840) BY LOUIS VUITTON; WATCH (CLIVE’S OWN) BY Jaeger Lecoultre.

Though Owen exudes enough personal charm to have famously been within a cufflink’s-width of being James Bond, his best roles tend to be the sort that, if not actively working against his charm, make the audience think twice about falling for it.

In Closer, for instance, he plays a doctor who rolls between charming the pants off Julia Roberts and emotionally abusing Natalie Portman, with both a perverted sexual energy and a heartbreaking romanticism roiling underneath. Theo, his sad-sack bureaucrat in the dystopian Children of Men, mopes onto the screen barely interested in continuing to live, all of humanity’s depression embodied in his tired eyes. Meanwhile John Thackery, his brilliant surgeon in turn-of-the-century medical drama The Knick, is as addicted to groundbreaking medical procedures as he is to both heroin and cocaine, and treats almost everyone around him like sacks of meat.

If none of these characters are people you’d like to have a beer with, though, they’re also hard to stop watching — and it’s that spark, Owen admits, that tends to attract him to roles, wherever they end up.

“They’re like tightrope walks,” he says. “You’re dealing in areas that are really difficult to keep people onside with. I want to try to take you on this very difficult journey, it’ll be a bumpy ride — but I find that exciting.”

That search for tightropes has most recently lead him back to London’s West End, where he’s currently starring in the Tennessee Williams play Night of the Iguana. It’s an under-appreciated work by the master, but the central role fits Owen’s MO perfectly: he plays a disgraced priest who has turned his exile for chasing underage parishioners into a drunken debauch across Mexico — until he’s stopped in his tracks by an encounter with a poet that threatens to reawaken his spiritual side.

SWEATER ($775) BY BOSS; PANTS ($855) BY BILLIONAIRE.

Though he’s only recently returned to the stage, Owen admits he enjoys the power that theatre grants to an actor, which is a serious switch from the precision and rigour filming demands. He confesses he feels that he was away from the stage for too long, and the return has given him a chance to explore different sides of acting as a craft.

“A play like Night of the Iguana is serious gym for an actor — the next film I’ll do, I guarantee I’m going to feel very powerful,” he says. “At the same time, with film, there is something great about putting everything, every ounce of what you’ve got into that specific thing — and then that’s it.”

“In character, I’m not there to charm you, but just to have a look at why a person functions like that.”

In some ways, Owen does seem ideally suited for film. He’s an artist of the eyes. There are his, made for close-ups, which can alternately burn with an intensity that lights up the screen or seduce someone in with that charm he’s always carefully controlling. More importantly, though, there are your eyes: Owen is someone who knows exactly how you are looking at him, knows not just what he looks like — which doesn’t hurt when you look like him — but also what each twitch and squint and stand and verbal explosion is going to say about him.

He’ll be showing off this talent in two films this fall. First, he plays a grown-up violin prodigy at the centre of a mystery in The Song of Names, debuting at the Toronto International Film Festival. And then he takes on the hefty action of Gemini Man, in which he plays a shady operative who has trained a cloned assassin to go kill his original.

SUIT ($1,515) AND SHIRT ($635) BY RICHARD JAMES.

As twisty as the plot gets, Gemini Man’s journey to the screen might be trickier still. It’s a script that has been floating around Hollywood since the ‘90s, and has been deemed by more than one director and studio head to be impossible to pull off. The dual clone parts require an actor — in this case Will Smith — to play two versions of himself about 30 years apart, simultaneously. It’s the sort of technical challenge that can make actors nervous: after all, there’s no level of performance that is going to rescue a CGI acting partner from the uncanny valley. Owen, for his part, is eager to take the risk.

“Talking about this film, my mind jumps to doing Sin City,” Owen explains. “That movie was totally green screen. It was like acting in space: there weren’t any props, there wasn’t even a car, just a stool to sit on. And it looked amazing in the end, it so effusively recreated the graphic novel — but, you know, I have no control over any of that. It’s the same here. I control what I can, and you have to trust the rest.”

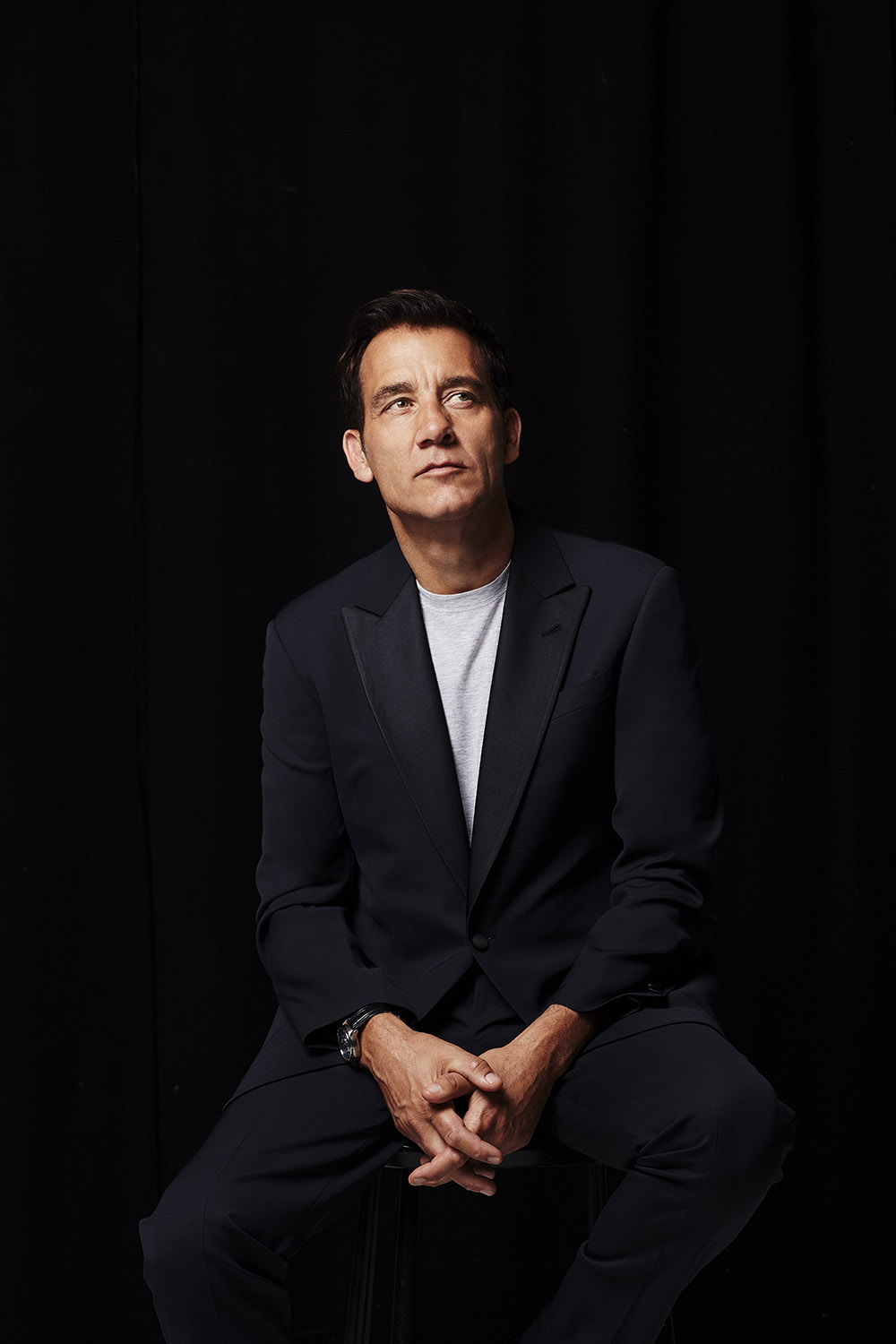

Coat ($1295) and v-neck sweater ($398) by BOSS; yarn-dyed cotton crepe crewneck sweatshirt ($370) by ZANONE.

He does at least freely admit that the presence of visionary director Ang Lee gave him the confidence to jump into the role — “If you can’t trust Ang Lee, who can you trust?” he says with another low chuckle — but if you drill down into it, you’ll get the distinct sense that it’s ultimately the challenge that Owen craves. If a slight prickliness unites some of his performances, the overarching shape of his career until now is that he almost never does the same thing twice.

As Gemini Man suggests, he has a certain taste for violence — that’s where you find conflicts and extremes — but even within his repeated shoot-em-ups, you run the gamut from blankly obsessed killers (The Bourne Identity) to conflicted crusaders (The International) to essentially, cartoon characters (the absurdly fun and literal-minded Shoot ‘Em Up). And all of those are liberally interspersed with turns as skeezy failed writers (Croupier), charm-oozing bank robbers (Inside Man), rom-com English teachers (Words and Music) and literary titans (Hemingway & Gellhorn).

Yarn-dyed cotton crepe crewneck sweatshirt ($370) by ZANONE; watch (Clives’ own) by Jaeger Lecoultre.

Owen, in short, is always looking to try something he’s never done before, which makes for an interesting actor, if not necessarily one that Hollywood always knows what to do with. There is a story about Owen in his first big Hollywood film, Robert Altman’s star-studded murder mystery Gosford Park, that seems indicative. During one scene, his valet is supposed to interrupt a conversation, but Owen felt it didn’t quite fit; he asked if he could instead just be seen listening in the background. “You’re in a cast like this,” Altman said to him, “with all these people, all fighting for space, and you want to cut your lines? Are you mad?”

“I still don’t know what kind of actor I am,” Owen explains. “For me it’s just about wanting to get interested in things and exploring them. I don’t really think I could be an actor unless I was prepared to step out and risk it and reach for it.”