Laid Bare: The Enduring Legacy of Helmut Newton’s ‘Sumo’

If the notional weight of a soul is 21 grams, as a physician once attempted to quantify, the soul of Helmut Newton, the German-born photographer who rose to fame and notoriety in the 1970s, weighs in at a hefty 30 kilos.

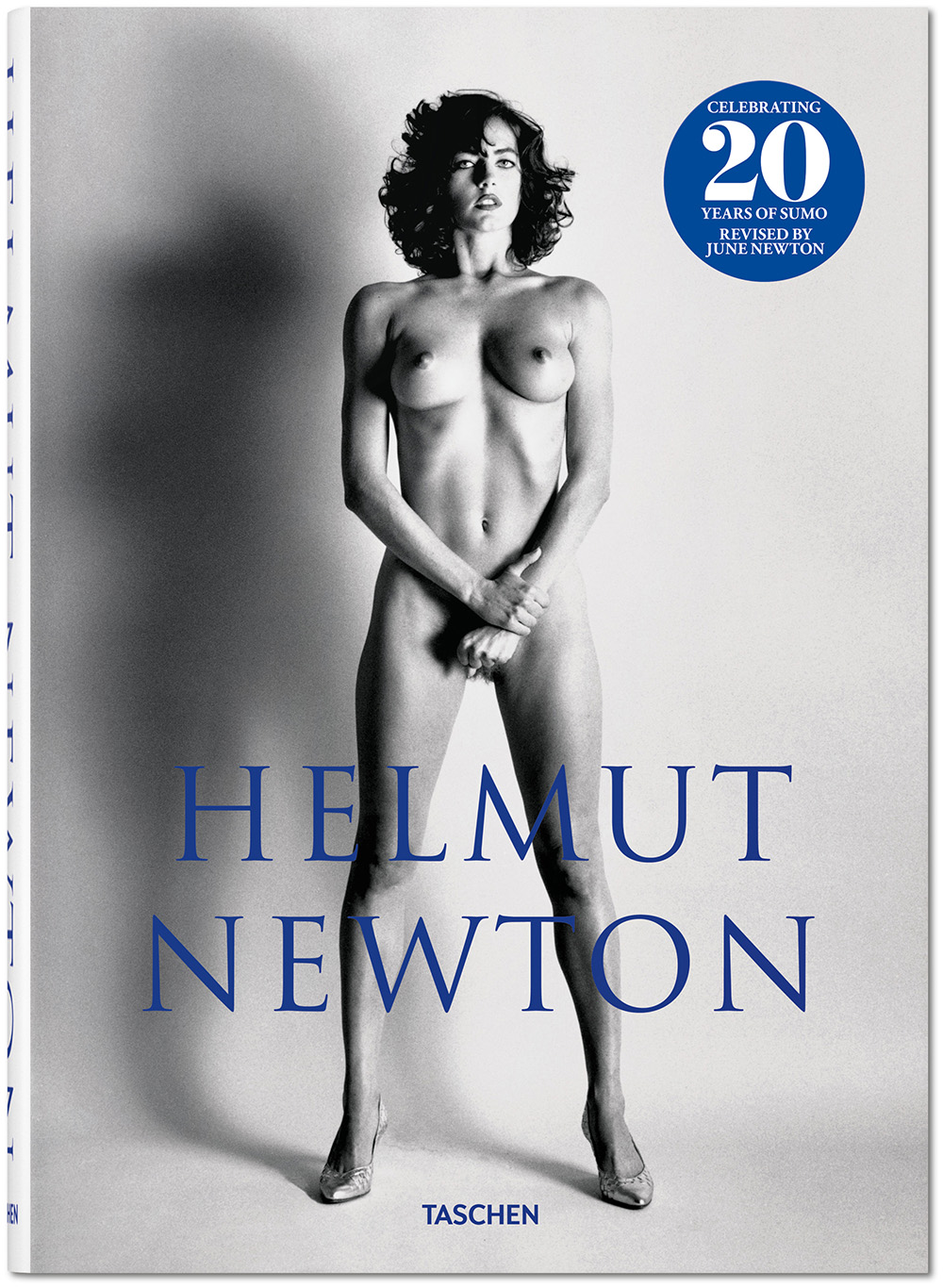

That’s the weight of art publisher Taschen’s monumental Helmut Newton: Sumo. The colossal 1999 monograph of the groundbreaking portrait and fashion photographer (1920-2004) was an extraordinarily ambitious publishing venture, and remains in several ways a cultural landmark.

Bound by the Vatican’s own bible binder, Helmut Newton: Sumo broke the record as the biggest and most expensive book production of the 20th century and it altered the landscape of the bookshelf. (Except that it didn’t fit on any bookshelf, with the possible exception of a Brobdingnagian library.) The book’s heft and dimensions (50cm x 70cm) make it so unwieldy it comes with its own steel stand designed by Philippe Starck.

“Not a coffee-table book, but a book with a coffee table,” is how Benedikt Taschen described his project in a Vanity Fair interview at the time: 480 pages and weighing 66lbs (the weight of an average ten-year-old), and limited to 10,000 signed and numbered copies.

This defining moment in art publishing has a before, and an after. In hindsight Sumo offered a renewed appreciation for print that gave the book object status: You not only can’t download it, you can barely even carry it. It re-asserted print culture, for one thing, because its publication coincided with the release of the first handheld ebook readers. A new millennium loomed and with it, angst about technology and Y2K even as the dot-com bubble fortunes continued to swell. For another, it created a marketplace where a book isn’t only an investment, it’s as much a stand-alone design statement as a prized original Eames chair; the Museum of Modern Art even counts Sumo among the design artefacts in its permanent collection.

“Newton famously remarked, ‘If a photographer says he is not a voyeur, he is an idiot.’ ”

The success also emboldened other art publishers like Abrams, TeNeues, Phaidon, Rizzoli, Aperture and Assouline to up their game with more deluxe titles. In more recent years some imitators have attempted to follow suit, at times with decidedly more preposterous results — Kraken Opus, for example, mixed Indian cricket star Sachin Tendulkar’s blood in with paper pulp to create the frontispiece page of their monograph.

Taschen was initially founded in the early 1980s as a comic book shop in founder Benedikt Taschen’s hometown of Cologne, a publishing company built on anti-art-snobbery principles and a strategy of making margins on volume with large print runs of well-designed art books and low cover prices. Matisse, Modernist architecture, pin-ups — until Sumo, the company was best known for its affordable Basic Art series of art history paperbacks.

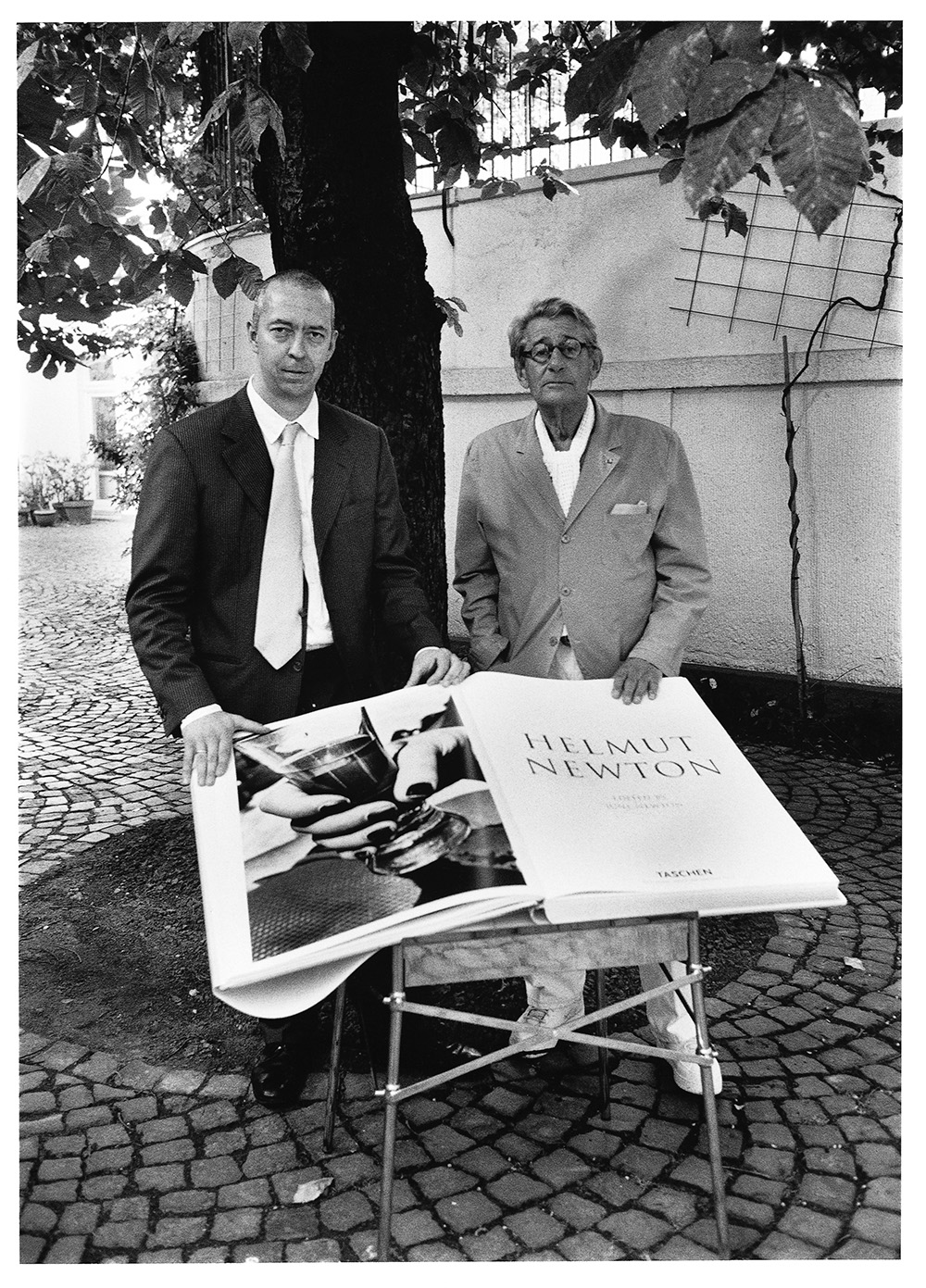

For Sumo, Taschen took the opposite approach. The original Sumo’s 464 images were chosen in a project conceived by Helmut Newton and revised and edited by his wife and frequent collaborator June. Encompassing all the genres, moods, and facets of his work, it’s a lifetime between the covers. As the story goes, Benedikt Taschen courted the photographer for over a decade, and they worked in Los Angeles with a team of fifty editors, photographers, writers, art directors, designers and bookbinders to create it.

If the definition of luxury is quality plus time, then Taschen was canny in highlighting the energy and resources involved in the gigantic book’s complex production process: the rounds of selection and proofing, culminating in Newton signing each and every one in blue crayon. Taschen not only had the sense they were doing something historic at the time — they helped to ensure its place in history by mythologizing the book through marketing and publicity that chronicled every step of the way.

“Working with Helmut is such an emotion, it’s not just standing there and being pretty,” Brigitte Nielsen explains in filmmaker Julian Benedikt’s documentary about the making of the book. “It’s about creating a special world.” As they sign their folios, a number of Newton’s boldface subjects are interviewed: “It’s very far out but it’s always got a beauty and an elegance to it, and a sense of style that you just don’t see,” subject David Lynch says of his fixations, while Sigourney Weaver thinks, “it’s all about his sense of humour…it’s very mischievous and he enjoys shocking people.” Vanessa del Rio is more succinct: “It’s just like masturbating your mind. That’s what I like,” she says.

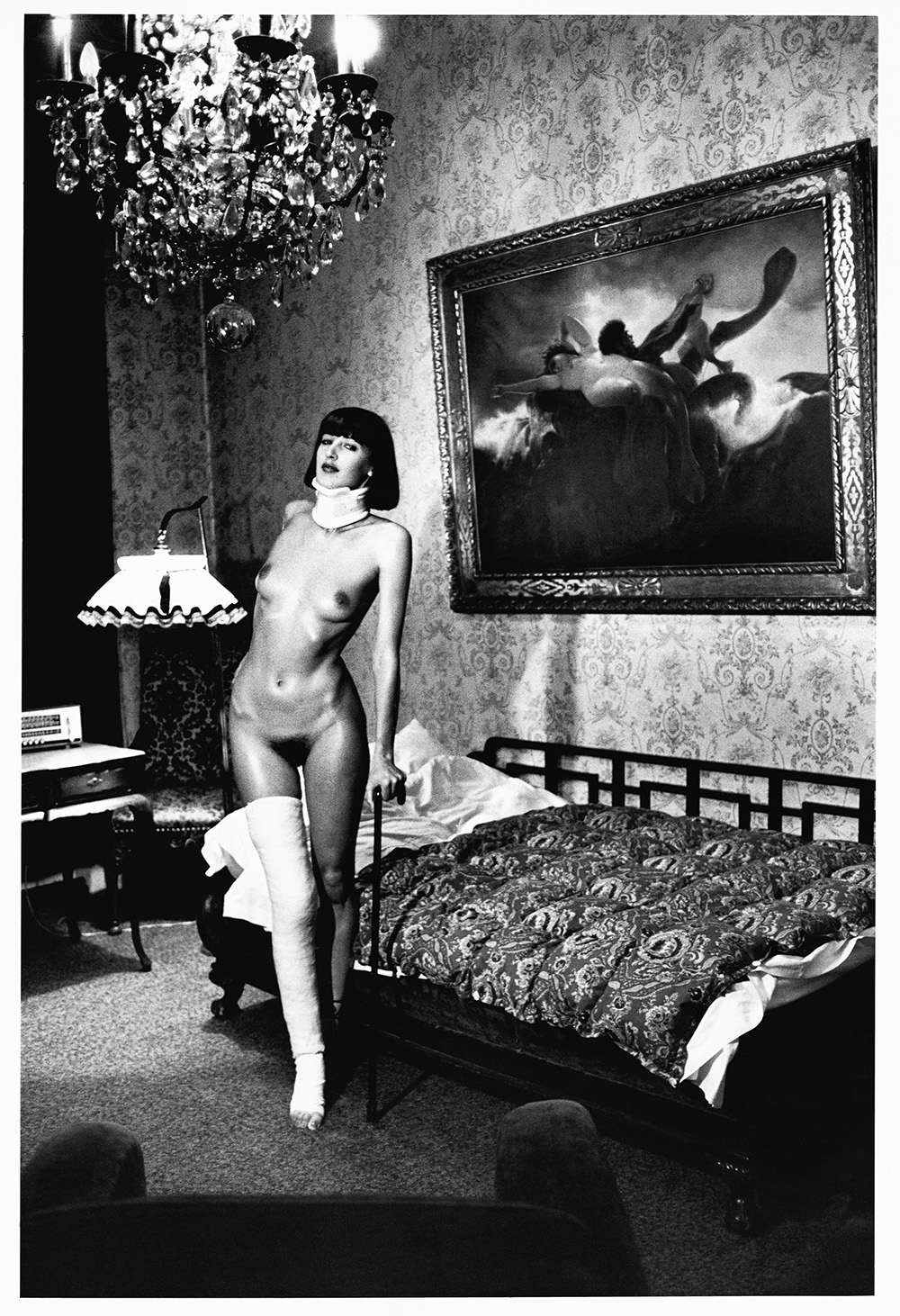

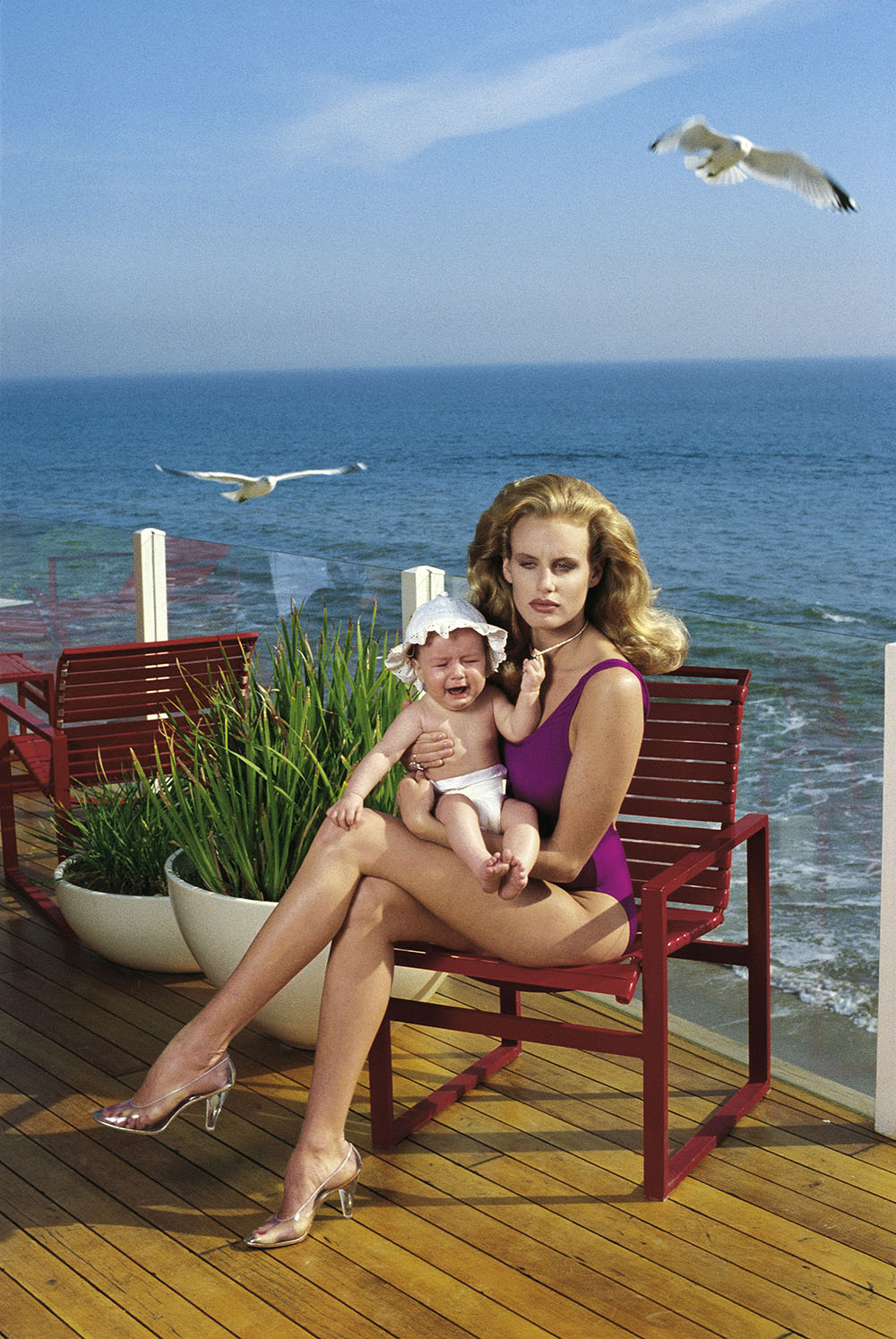

“If a photographer says he is not a voyeur, he is an idiot,” Newton famously said. And one of his legacies is the commingling of couture with explicit eroticism in magazines like French Vogue, Elle and Stern, and bringing stylish soft-core pictorials to the pages of Playboy. Anna Wintour describes his work for her magazine as “synonymous with Vogue at its most glamorous and mythic.” In both fashion photography and his nudes (and they’re often interchangeable), Newton mines memories and projects fantasies of Berlin. Newton’s 1979 shoot in Berlin for the German edition of Vogue was an era-defining sequence, for example.

A peek through the keyhole before the everyday voyeurism of Instagram culture, naked or clothed, Newton’s poised and sensuous glamazons brought his particular uninhibited fetishism, voyeurism and distinctive erotic taste into the mainstream. Hugh Hefner said that Newton, “used his fashion photographer’s eye to make the erotic almost surrealistic.” He was as influential as he was controversial, according to fashion historian Valerie Steele. “Although sex is an abiding theme in fashion photography, certain types of sartorial eroticism arouse more controversy than others,” the director of the Museum at FIT wrote for Aperture, in an essay about how voyeurism and exhibitionism are intrinsic to fashion photography, specifically citing the more sexually explicit 1970s work of Newton and his contemporary Guy Bourdin. The assertive female stance and the way Newton’s lurid compositions express, “a very European sense of sex with love (or regret),” Steele points out.

The Seventies were a time of radical social upheaval and France — then still the undisputed capital of high fashion — was ripe for aesthetic change in the wake of the May 1968 student protests. Contemporary photographers like Newton fed on that energy. His models break with tradition by coolly meeting and challenging the camera’s gaze, like a hauty haute bourgeoise. (Or as Jodie Foster opined, Newton brought to the female nude a new language of strength, instead of being passive it’s very active.)

In 1975, when the New York Times chief art critic Hilton Kramer argued that contemporary fashion photography was becoming a sub-division of pornographic culture (“chilling in their taste for perversity and violence”), he singled out Newton’s boundary-pushing pictures as “so clamorous and unsavory that the pictures insist on being judged by the standards of another genre.”

Sumo is the scope of Newton’s work, from pop culture fashion homages to North by Northwest to stylized and staged stark scenes reminiscent of Weegee, the crime photographer he once aspired to be. Stockings and garters and tan lines and harnesses and heels — just as often naked, and styled with Newton’s arsenal of regular props (“the chains come in really handy sometimes,” June explained of how Newton usually carried props like chains and a pair of false nipples in his photography kit). He was a gleeful provocateur: In 2003 after Vogue ran his “Knee High” photograph of a woman in a lingerie cleaning blood spatter from the taped outline of a body on the tile floor, executive editor Phyllis Posnick recalled in an interview the fax he sent. “Dearest Phyllis, I’d love you to fax me the anti-Newton letters for my archives! Thanks a million. Love as ever, Helmut.”

There’s something of that unsettling, shocking elegance in Newton’s celebrity portraits, many are definitive of their famous subjects, from Luciano Pavarotti in his dressing room, INXS frontman Michael Hutchens in chains, and fellow German iconoclast Karl Lagerfeld dandified and squinting into a glass lens like a monocle to Catherine Deneuve in a slip with a cigarette between her teeth (for Esquire, 1976) and late-period Elizabeth Taylor submerged in a pool. Entire series are revered, like the one with frequent muse Charlotte Rampling that culminates in her posed naked on table, legs akimbo, in an ornate hotel suite. Others are infamous, like a portrait for the New Yorker in 1997 of Jean-Marie Le Pen with his Dobermans that instantly (and supposedly unintentionally) invoked the series of Adolf Hitler with his German Shepherds.

Even on the resale market Helmut Newton’s Sumo raised the bar — and the prices. In the secondary book market it’s not uncommon for art editions to double or triple in value, but with Sumo, they go up tenfold. With record-breaking art auction prices, it was a book that made headlines. No. 1, also signed by dozens of the photo subjects it featured, sold the following year at Berlin auction for US$430,000. A decade later, Taschen released a more modest (but still lavish) version reproducing (it weighed only 15lbs), still recession-proof with its own Lucite display stand (re-release) that also goes for elevated prices. The new 20th anniversary edition is a slipcased hardcover and comes with a making-of booklet.

It arrives to a very different world. Published into a post-supermodel, post-ironic culture, the new edition will find a new generation of readers, who may well be inured to Newton’s original provocation. But in a regressive political climate challenging women’s rights on all fronts, they may also discover a new appreciation for his nudes, their insolence and agency, and find resonance in their assertive, unflinching poses.

Taschen went one better in 2003 with an immodestly titled follow-up — the Mohammed Ali tribute book GOAT (Greatest of All Time). The Champ’s Edition is signed by the icon, its 800-page tome presented in a silk-covered box with limited-edition Jeff Koons art piece. Other artists whose work has subsequently received the lavish Sumo treatment have included David Hockney, Sebastiao Salgado, The Rolling Stones, a collectors edition of Christo and Jeanne-Claude that came with an original sketch, and Annie Leibovitz (with four cover images to choose from, and a tripod bookstand by Marc Newson).

The fetish in the book transferred to the book itself and elevated an art book to status symbol, ostentatious and even vulgar. Whatever you call it, Sumo pioneered luxe lit as big business.