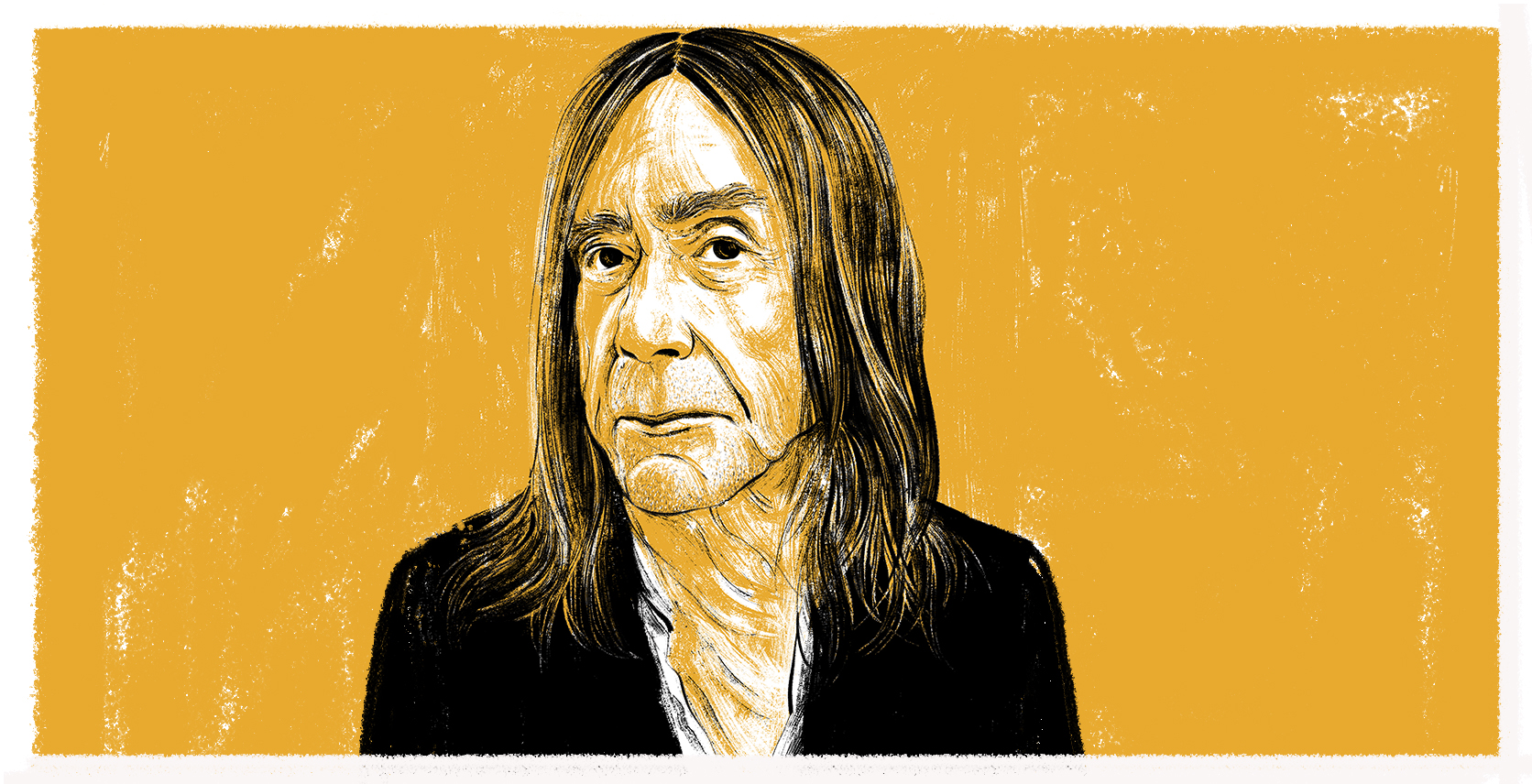

Iggy Pop Lusts For Life

Iggy Pop doesn’t play punk — he is punk. Every lyric howled by the 72-year-old blazes right through five decades of cliché, a fireball of authenticity from an era when everything seemed original. As the Stooges’ feral frontman in the late ’60s, he set the template for punk rock well before the Sex Pistols discovered hair gel. So punk was Pop that he’d spend most of his career playing music people didn’t get, struggling commercially and failing to crack the mainstream even after recording two ahead-of-their-time albums, The Idiot and Lust For Life, with David Bowie.

Which is why Iggy Pop is so thrown by this late-career high he’s having. Look at him now, mugging for Gucci’s Cruise 2020 campaign, starring in Jim Jarmusch films (The Dead Don’t Die), and boasting number-one albums (his 2016 effort, Post Pop Depression, was his first ever). He’s survived long enough to get his due from the culture while remaining idiosyncratic enough to stand defiantly outside of it. Case in point: his new LP Free, which features avant-jazz meanderings, zero hooks, and his naked body, standing in an ocean, on the cover. What’s more punk than that?

You’re quoted as saying that after your last album cycle, you felt you’d finally rid yourself of your “chronic insecurity.” You? Insecure? Since when!

I’ve always had a lot of confidence in what I was doing, but my numbers were always very small, especially starting out. Also, my style was really outrageous to the industry, so I had

a lot of problems getting backing, getting finance. I never had any security that I would make the next record, and I had lots of trouble maintaining my integrity because they’re always trying to water you down. But then the century changed and, little by little, my numbers just kept getting better — all through the Stooges’ reunion, people started putting out Greatest Hits albums and using my songs in films. Then finally, with the past five years, the whole thing took a big step forward. All of a sudden, I could finance my own records easily. I didn’t have to worry about record company support, or a lot of things. I’m a very good size at the moment, which is nice after all that time.

At what age would you say you felt like you’d finally made it?

Well, I don’t know. I feel like I’ve fulfilled whatever talent and skills I have to a proper level. So, I feel okay about that. Life is uncertain and nobody has it made in the shade as long as they’re breathing on the planet, but I just feel like things are about right now. I did the job and I’m in the book.

The new record is called Free. What are you referring to? Artistic freedom?

Just a lot of things. I just wanted to loosen up — loosen up the strings of my puppet control. [Laughs.] I wanted to loosen up the strings of life and be a little freer on all the different levels. You usually have to demand that sort of thing, and one way is putting out something like this. I mean, this is not the album where you would sit down with the currently hot producer and the guy from the record company and say, “Okay, here’s our strategy to sell a lot.”

“MTV videos were stupid. Now there are eight million people on YouTube to see me sing ‘The Passenger’ live and whacked out of my mind. This century’s been great.”

But your strategy’s never really been to “sell a lot,” right? When the Stooges first came out, neither critics nor audiences liked you very much.

No, they fucking hated it. Yeah. [Laughs.] And the label became a problem. I was pretty ferocious at that time, saying, “Just leave me alone, don’t give me any shit.” And they’d put up with that for a couple records and then drop me. So, I’d have to go hustle somebody else. I managed to put out about seven really good records through sheer…just balls, to tell you the truth. Just balls. And then for about 20 years after that, it was a constant fight to try compromising with the record companies. I’m a pretty weird bird, so any little thing is a compromise for me. Like, I didn’t want to make MTV videos; I thought they were stupid. But I got talked into that. When I look on YouTube now there’s eight million people who want to see me sing “The Passenger,” whacked out of my mind within an old horse tail, live at Manchester, filmed with a Super 8 — and only a few hundred thousand want to see me sing something directed by the video guy of the moment in 1987. But this century’s been great. It’s weird: I’m getting all the work and offers that I wished I’d had when I was 23, but instead I’m almost 73. [Laughs.] Pretty funny but I’ll take it. I’m ready!

What’s funny is many millennials today can probably relate to young Iggy — being in your twenties and broke but having a dream. What’s your advice to all them struggling millennials out there?

Well, I would say to keep the dream. And to try to preserve the dream in a nice, pure state but then also develop a nasty little crooked side. [Laughs.] Get in there and do some dirty work to get your shit across but try to balance the two, and when you have to give in a little, know when that is. Just listen to the little angel inside but also listen to the little rat inside.

On one track on Free, you narrate the Dylan Thomas poem “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Do those words resonate with you especially now, in your seventies?

Well yeah, not so much. It’s funny. I originally did that poem for an ad agency commercial. What I like about it is within the poem, each sort of individual that he writes about — the wise men, the good men, the wild men, the grave men — has a little surprise near the end where they think, Oh shit! That’s where I fucked up. That’s why I decided to re-record it. And I realized that people think about that now when they think about me, so I might as well deal with it.

But you’re taking the poem’s advice, no? Don’t you still feel a desire to keep raging?

You know, I don’t feel like King Kong these days. Put it that way. [Laughs.] It would be great if I could be Julio Iglesias but I’m not quite there. So, I’m somewhere in the middle, between Kong and Iglesias. I’m smoothing out, definitely. You do get a little softer, but I do have a powerful rock band. We do a very good performance for anyone — millennial or younger — who wants to see what it was like when there were still people like me, because there’s really nobody who performs in that style anymore. In many parts of the world I get a lot of screamers in the front row, because they’ve seen video of kids screaming in the ’60s and ’70s and they want to do that. [Laughs.] They’re like, “Yeah, we’ve got this guy leftover from the ’70s. We could go out tonight and scream!”

How do you feel about being designated “the Godfather of Punk”?

It started out sort of like “Iggy” — it was a thing people used to say. My rhythm section in the band for The Idiot used to call me “Godfather” just to embarrass me. They were professional musicians who’d never dealt with punks and all the people coming to my show were punks. So, they would say, “You’re the godfather of these people!” But somehow it stuck around. There was stuff in my work that provided basic templates for some of the punk that followed, so that’s a good position to be in: being of use to what came next. Especially because the only legitimate rock there is today is punk. I mean, all the legitimate bands — Fucked Up, Death Grips, Sleaford Mods, Idles, Viagra Boys, Raketkanon — they’re all pretty fucking punky. I don’t really go for the Led Zeppelin redux crap. So, I feel like, you know, I’ve made a contribution.

You’re credited with inventing the stage dive. When you first leapt into a crowd, what were you trying to accomplish?

It was 1968. We were opening for the Mothers of Invention at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit. I was trying to make sure everyone would remember me and my band because we were just the opening act, dude! [Laughs.] People were just sitting there in the dark, staring at us thinking, What the fuck is this? So I was trying to connect with the audience. I was upping the ante on Solomon Burke and the great R & B singers of the time — at a certain point in their show, they would step off the proscenium, walk through the crowd, and work the house. I just thought, well, instead of that — you know, this is a new, more hyper world where everything is sped up. It was the age of the hot rod and the muscle car. So, I’ll dive on them!