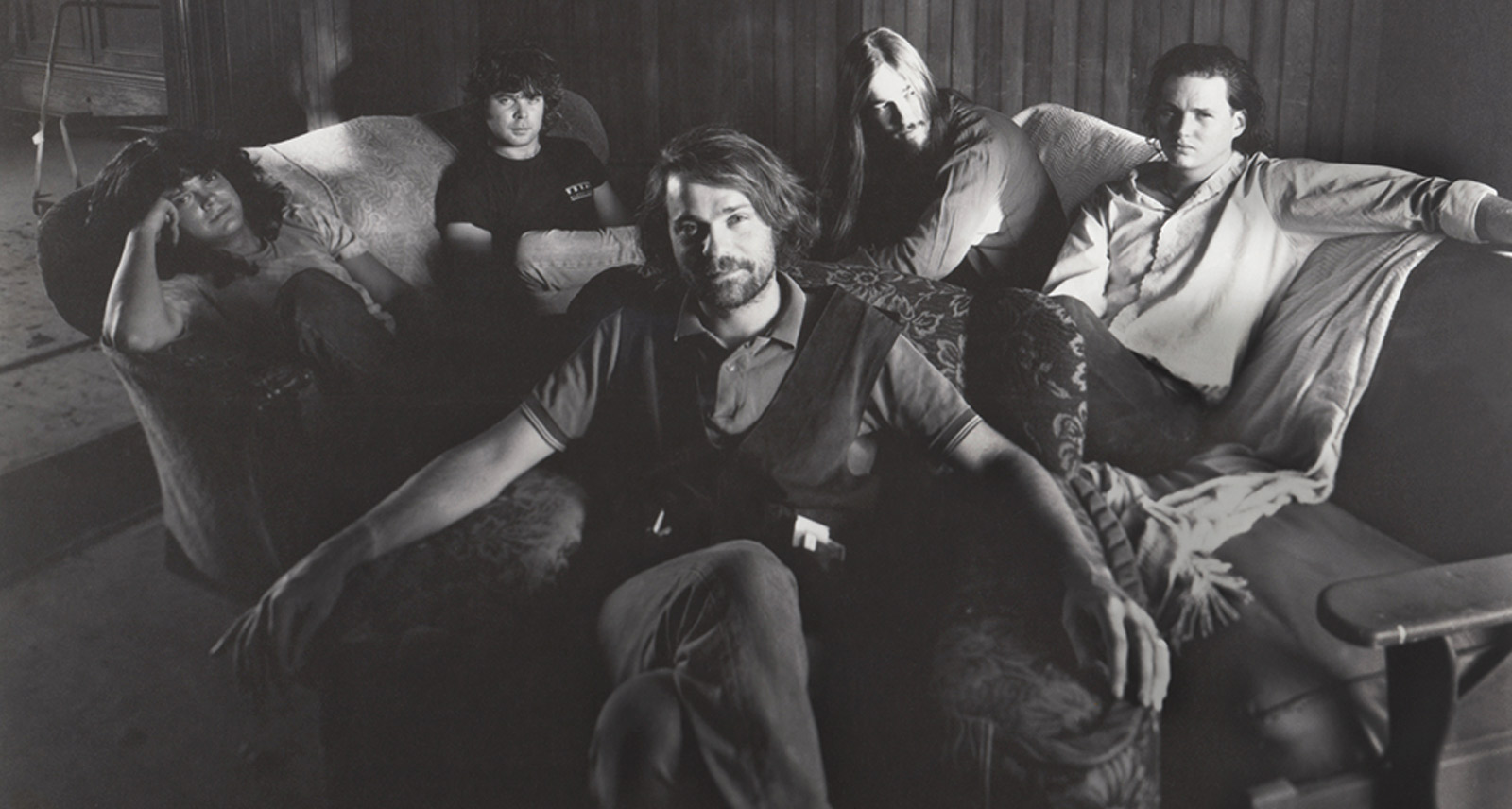

The Tragically Hip on the Making of Surprise New Album ‘Saskadelphia’

In 1990, The Tragically Hip found themselves in New Orleans to work on the follow-up to their platinum-selling debut album Up To Here. After heavily touring Canada and the U.S., the Kingston, Ontario, rock band — singer Gord Downie, guitarists Rob Baker and Paul Langlois, bassist Gord Sinclair, and drummer Johnny Fay — were a well-oiled machine, and had a wealth of material to choose from. Working with producer Don Smith and engineer Bruce Barris, the band recorded 1991’s Road Apples, which cemented the Hip’s reputation as a group to be reckoned with.

Now, two decades after those recording sessions — and four years since Downie passed away in 2017 from brain cancer — the band has released Saskadelphia, a collection of six tracks that were left off Road Apples. “I was very hesitant to push play,” Langlois tells Sharp. “I thought, ‘Well, they didn’t make the record, they’re not going to be that good,’ and it was quite the opposite.” Before all the accolades, awards (17 Juno Awards, the Order of Canada), and arena shows (including their final 2016 concert, which was broadcast and livestreamed on CBC, and reached 11.7 million people), rollicking songs like “Crack My Spine Like a Whip” and “Reformed Baptist Blues” showcased a quintet eager to prove themselves and deeply committed to their craft.

From their respective homes in Kingston and Toronto, Langlois and Fay discuss the making of Saskadelphia, the Hip’s enduring reputation as “Canada’s band,” and Downie’s legacy.

Tell me about the process of finding these songs — because I understand you weren’t sure if some of them even existed anymore.

JOHNNY FAY: I think all of us had talked over the years of unearthing some of these songs. For Road Apples especially, we went in super prepared. When you make a record, you never know if you’re going to make a second record, and our manager Jake Gold said, “When you’re on the road, you’re going to be preparing for your next records.” We always knew that these songs existed, although we might not have necessarily known the titles. We heard about the [2008] fire at Universal Studios and what was really alarming to us, Robby pointed it out, was that we were mentioned in a New York Times article. So we were sitting there wondering if we had songs in this fire, and what had happened was the majority of stuff had been transferred up after [1992 album] Fully Completely. So in an iron mountain somewhere in Toronto were tapes. The process involved going up there and looking at boxes with no writing on the back, just writing on the spine, but it had been changed so many times that we could see our engineer’s writing, we could see our assistant who was with us, Mark Vreeken, we could see his writing on it, and then all these other numbers. We really didn’t know until we took the tapes, baked them, and then listened to them. That process took about two years.

Obviously, New Orleans has a long, rich musical history. Was the band aware of that and did it influence the music you were making in any way?

Paul Langlois: I think we noticed; we were totally excited. We had done our first record in Memphis, which was cool, but it wasn’t like the full-on Memphis experience. Don Smith, who produced Up To Here, was going to produce Road Apples, so we were very excited to work with him again. He instilled a lot of confidence in us; he didn’t try to change us. He just wanted us to get the takes right and be ourselves. We were going to [producer Daniel] Lanois’ place — and it’san old mansion, the vibe was great, the people who worked there were great. We didn’t stay there that time, we were like a block away in the French Quarter. We soaked it all in and we were excited. New Orleans played a big part in itbecause we felt like “Man this is it, we’ve arrived, we’re in New Orleans,” We went out and there’s music everywhere. In hindsight, it was probably our best recording experience, we kept trying to recreate that and trying to recreate that in our studio [The Bathouse].

Where did the title Saskadelphia come from?

JF: We used to do this thing where we would sit in front of a chalkboard and throw titles out. I remember driving and, I think it was near Kingston, there was this church called the Church of the Christadelphians, and I was like, “You can graft one word onto another, ‘delphia,’ what does that mean?”At the time, we were playing similar clubs in the United States and Canada, and you wondered where you were half the time because the clubs kind of looked the same. Our record company didn’t like the name because they were U.S. and they thought Saskadelphia was too Canadian, so we gave them Road Apples, which was the most Canadian thing, which is what Canadian kids play hockey with out in the prairies.

Was “too Canadian” a criticism that you received a lot in those early days before you had a few records under your belts?

PL: My personal opinion is we sort of got pigeonholed a bit later in our career for being “Canada’s band.” Hey, we all love Canada, we’ve all chosen to stay here, we’re all proud to be from here. Our crowd in Detroit versus our crowd in Austin versus our crowd in Amsterdam or Copenhagen, we treated it all the same. It’s something we didn’t really like and we resisted, but only to a certain extent, because you can’t control this stuff. But we were as proud of our history in Boston as we are proud of our history in Toronto. We worked our way up in all these places, and it really depended on the city. In Europe, especially in Holland, but in other countries too, they came out to see us because we had come over from Canada. We appreciated that we started with full rooms there. If we could start with a full room, well, we could keep that room full. It’s when you start with the empty room, and that’s what the case was in Canada and the United States, empty rooms, so we just had to build it up. We treated the two countries the same.

When this album was recorded, you guys were in your late twenties. If you could go back in time and give that Hip any advice about navigating the industry and the success that followed, what would you say?

JF: Don’t change a thing. Because we had this most incredible band called Rush — they’ve influenced Metallica, Pearl Jam, countless other bands. They did everything on their own terms. When people told them “This record’s not going to be accessible,” [1975’s] Caress of Steel, they were like,“No, this is our record.” If you can do your music on your own terms like that, you don’t change a thing. Gord Downie always said, “We’re a slow-moving freight train; we’re going to do it on our own terms, just don’t get in our way because we’ll drive over you.” We could’ve taken shortcuts, and then we all talked about it, we were great communicators about these kind of things. I believe we really lived in a golden era of Canadian music, we were very lucky. Lucky to find like-minded people that were going to commit to each other, we believed in each other, and we knew that we could do it on our own terms.

PL: I totally agree with everything Johnny said. We felt lucky back then. I felt really lucky because I joined the band last, and I think I was still the new guy on our last show. We were having fun, but we were all showing up on time, we all knew the songs, we all knew what was happening two months down the road, we would show up for tour. We didn’t have any personal problems — a stroke of luck; people can’t control that, you can try. We were always kind to each other. So I don’t look back at any of it with any regret whatsoever. I would credit Gord Downie; he couldn’t let anything lie, so if there was some type of issue Gord wanted to talk about it. We all sort of became that way, so we weren’t walking around with a bunch of issues, we took it seriously. There’s a lot of complications in a band. Our biggest achievement is that we’re all still friends. It’s tragic that Gord’s gone, but at the same time, he believed in us, and we believed in him and each other.

This October will mark four years since we lost Gord. What’s one lesson he taught you that you frequently find yourselves returning to?

JF: I was talking to a friend the other day and saying there were two voices that would’ve been really incredible to have had around during this pandemic: Gord Downie and [Rush drummer] Neil Peart would’ve looked at it from a crazy angle. Those two writers are gone now. For me, and I’m hearing it on Saskadelphia, Gord was a guy who had to believe it, he was very real and he was in the moment. If you were in the room with him and he was talking to you, he had his eyes locked on you and he was there with you, he wouldn’t look over shoulders. He sang about these things that he had to observe, he had to experience, and then they were in his imagination. He could weave stories together with a kernel of reality and then his imagination.

PL: It’s funny, because I think he would’ve looked at me like his advice-giver, like as kids before the band and everything, and that’s not really the case. He was such an example of putting the work in — it wasn’t an accident, he was reading like crazy, he was interested in everything. “Born in the Water” on Road Apples, who came up with that? Maybe the subject came up once in the van. He just tackled the subjects; it was really quite the example of doing the work and he always did the work. I remember asking him because I was going to do this solo gig or whatever. It wasn’t really that normal for us to have this type of conversation, but I was like “What is it that you do on stage, what’s your thought process like?” and he’s like, “I just crack the whip man.” It reminded me of “Crack My Spine Like A Whip.” I was like, “Okay, I’m trying to understand it, “You just gotta look at the crowd and crack the whip.” It’s always stuck with me, I don’t exactly know what he meant.

You’re both fathers. What’s your kids’ relationship with the Hip’s music like? Do they ever turn you on to new music?

PL: My girls are 25 and 21, and Johnny’s boys are seven now. My girls don’t bring it up — they wouldn’t bring it up with friends, like, “Hey, my dad’s in the Hip.” It’s a subject to be avoided all the way through high school, university, but people find out. They like it. Better that than — I could insert the name of many bands. At least it’s not embarrassing to them. They both play guitar, but probably despite my efforts to get them to play. When I finally left them alone, they both learned how to play, so they have that kind of friend for life. They’ve turned me on to some music, but you get to be a little older, I’m not really searching for new music. If I hear something that they’re playing — they don’t live here anymore, but when they were — the odd time I’d be like, “Oh, this is cool.” Most of the time, it’s not really my thing, but they’re happy about it and there’s a whole bunch of band kids, they’ve always been great. It’s neat that Johnny’s got newer children, really looking forward to getting to know them. They’re going to have a bunch of cousins who will be able to tell them about all the great times they had in and around our shows.

JF: My kids are not familiar with the Hip at all. They know that I’m a drummer, they were two years old when we played our last gig, they remember coming to sound checks and things like that. They know that the singer passed away, our friend is gone. Sometimes a song will come on the radio and I’ll say “Guess who’s playing the drums!” and my son will say “Stewart Copeland?” because I would always say he’s the greatest drummer on earth. It’s not a shame, it’s just part of life. I didn’t have kids during these periods of making records and going on the road, and how difficult it must have been, because I don’t think I could leave. These guys were on the road for a lot of important things; you’re in a band, you miss anniversaries, birthdays, funerals, weddings — you miss it all. You put yourself out on a rock. Talk about isolation — I could see the things that were happening in their lives, first footsteps, first words. We used to have to pull over to the side of the road on a Sunday — there might be two phone booths in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania, and we’d make the bus driver pull over and we’d all make phone calls to girlfriends and wives. I think Paul had a pager at one point, but that was our way of communicating. We are one big happy family, and when their kids came to gigs, it was always that extra-special day. If it was a summer day and we were playing a gig and the families were all there, the people that work with us would make it like an event for them, and that just made us an even bigger, better family.

Lead Image: Jim Herrington