Just before 1 P.M on a recent summer afternoon, Gísli Matt is in the kitchen butchering cod wings. It’s slimy, gritty work, and even when the fish are fresh — recently procured from the harbour just steps away — it’s less than glamorous. But somebody has to do it.

Cod — which float off the shores of Iceland as freely and plentifully as deer roam the Scottish highlands or sheep the fields of New Zealand — don’t really have wings. They do, however, have a kind of stiff collarbone that holds the rest of their thin skeleton together. Most people — even the world’s most accomplished chefs — rarely bother to use this part of the fish. Gísli Matt does. He’ll serve them deep fried, almost like chicken wings, topped with a bright orange hot sauce and local herbs. They’re a signature appetizer at his restaurant, Slippurinn. And, in some ways, they’re the key to his whole culinary ethos — the reason he’s become, at just 32, one of Iceland’s most important chefs.

When Matt opened Slippurinn a decade ago, it seemed crazy on just about every level. For one, he was young and fairly inexperienced. He’d trained in Reykjavik and staged at a few restaurants and banquet halls, but he’d never run a kitchen — let alone a whole business. Also, it wasn’t exactly easy to get to. Located on the archipelago of Vestmannaeyjar, a 40-minute ferry ride (in good weather) from the mainland and about a three-hour journey from Reykjavik, it’s one of the more remote fine-dining restaurants on the planet. It’s also big, housed in a former machine workshop in the island’s shipyard. And then there was his insistence on using almost exclusively local products harvested from a rough, windswept landscape that isn’t exactly hospitable to produce.

“We didn’t know what we were doing, basically,” says Matt. “But we knew what we wanted to create. We wanted to build a restaurant that we would be proud of, and hopefully the community would be as well.”

The community rallied around the restaurant almost immediately, partly because Matt insisted on using anything he could find from the area, including fish sourced directly from local fishermen — one of whom happens to be his own father. He also believed from the outset that while tourism would of course play a large role in the business, the food had to cater to local palates, interests, and wallets first and foremost. Today, he estimates that 70 per cent of his clientele is Icelandic. For many diners, his restaurant offers an opportunity to rediscover the tastes of their childhoods, or ingredients few other chefs would have the temerity to use. “Over the last 50 years, people have been forgetting what Icelandic food was like,” he says. “We really want to hold strongly to a lot of older recipes. Rather than forgetting them, to put our own spin on them, to elevate them a bit.”

These include a recipe for halibut soup derived from one his grandmother used to make — just not for him. Matt read about a similar soup in an old newspaper and asked his grandmother if she might have a similar recipe. He took it, tweaked it for the modern palate, and, in the process, he found his culinary footing — and the reason for Slippurinn’s success.

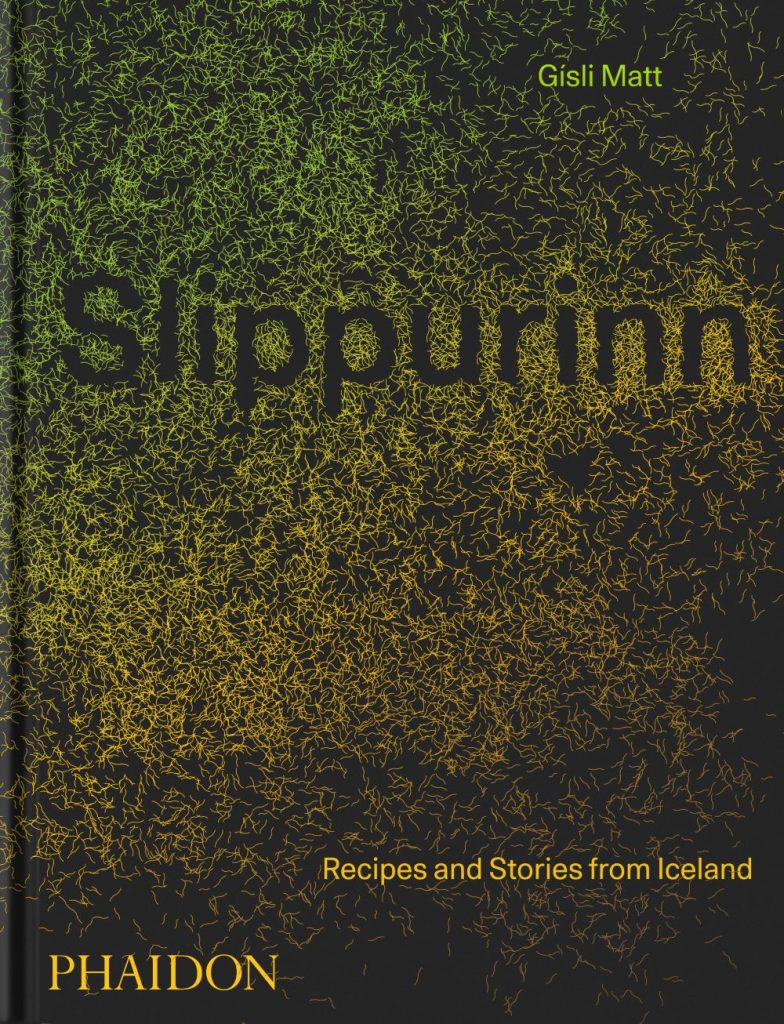

The halibut soup appears, among other favourites, in a beautiful new cookbook released by Phaidon this fall. The book is a chance for Matt to tell his story, and the story of the unique landscape that has inspired him. Slippurinn: Recipes and Stories from Iceland is equal parts travel guide, foraging manual, and manifesto on what it means to cook locally, live simply, and eat well. Readers will come away with an almost encyclopedic knowledge of the island’s bounty, from the herbs defiantly growing underfoot to the fish swimming just offshore.

The book’s foreword is written by Carlo Petrini, founder of Italy’s famed Slow Food movement and perhaps the world’s most notable advocate for eating locally, seasonally, and conscientiously. Petrini’s stamp of approval is a big one. The work Matt is doing at Slippurinn may be rooted in his local geography, but it’s much larger than Iceland’s borders. The choices Matt has made have not always been easy ones — but they have always been determined, and rooted firmly in his philosophy, in his own sense of self.

“Hopefully, this book will inspire some young people to not only open their own restaurant, but to maybe create something they want to create,” he says. “We wanted to build a restaurant in our small community we were born in, and hopefully people seek some things from our story to do what they want to do, not only follow others.”

That ethos has served Matt well — and not just in business. He deliberately opens Slippurinn only seasonally, in summer, so that he can spend the rest of the year working on new projects and learning as much as he can. He’s involved in two other restaurants in Reykjavik, both very different and more casual than his flagship on the islands but no less grounded in Icelandic cuisine. He also takes the time to travel the world, staging at Michelin-starred restaurants in New York, Paris, and Copenhagen.

Mostly, though, he spends what little free time he has with his wife and four young children. “I really want to be a good father,” he says. “So there are things you need to sacrifice, like maybe my social life is not the best. But I’m not complaining. We live a really good life here.” And if you’re lucky enough to travel again soon, all the way to the island of Vestmannaeyjar off the southern coast of Iceland, he’d like to share that good life with you, one lovingly butchered cod wing at a time.

All images courtesy of Phaidon.