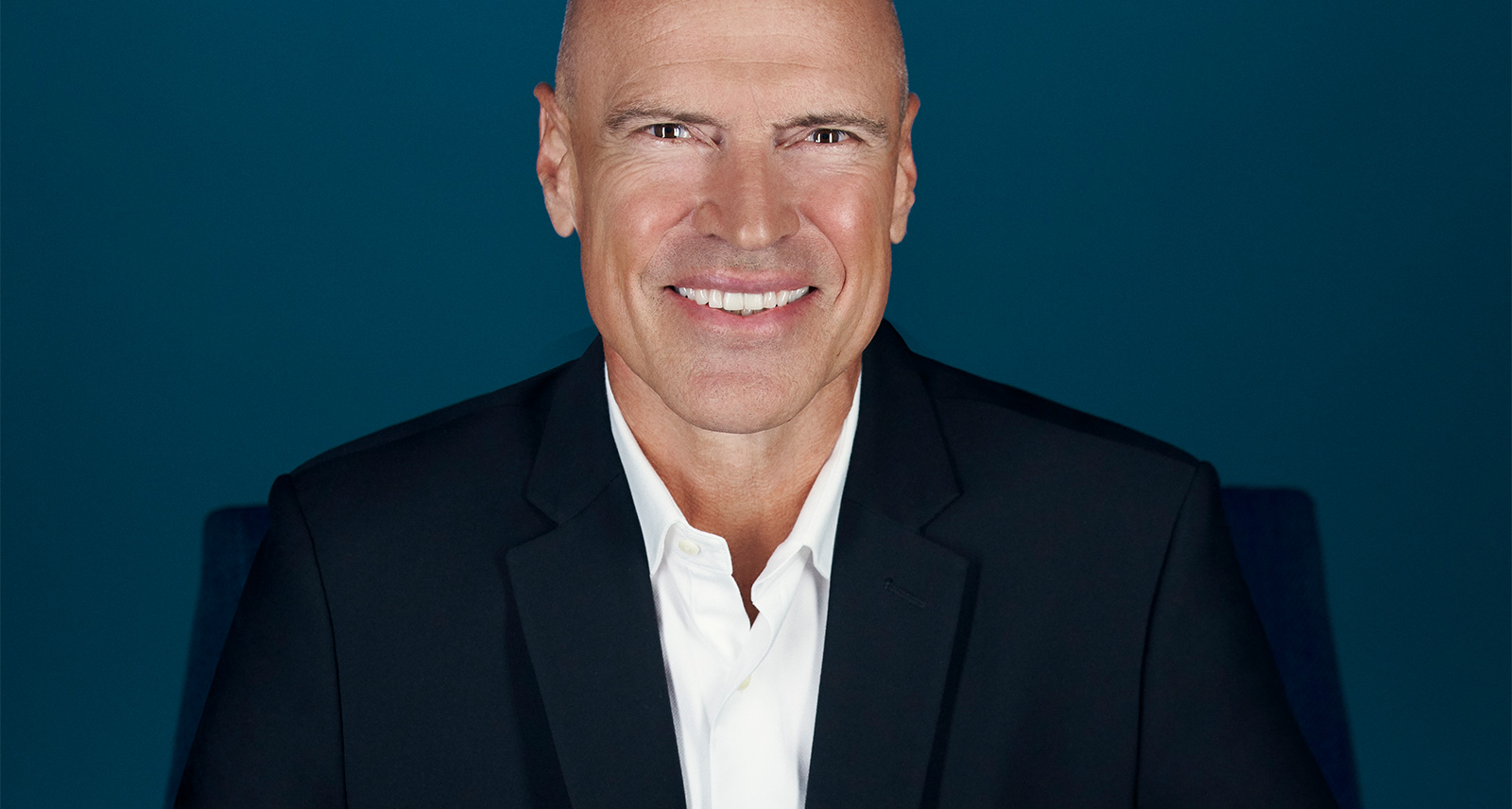

Mark Messier on What Makes a Good Leader and His New Memoir ‘No One Wins Alone’

If you’re reading SHARP, there’s a good chance that you’re Canadian. And if you’re Canadian (and even if you’re not), you likely know Mark Messier. And for good reason: he is one of the greatest hockey players of all time. That’s indisputable. With a pro hockey career lasting 26 seasons, Messier sits near the top of the ledger in most of the NHL record books. He has, for example, played the third-most regular-season NHL games of any player in history (add in the playoffs and no one has ever played more). He sits third in assists. And, similarly, he sits third in total points, behind only Wayne Gretzky and Jaromír Jágr. Beyond stats and individual accolades, Messier was also a legendary leader and captain, having worn the “C” for the Edmonton Oilers, New York Rangers, and Vancouver Canucks. In fact, he’s the only player to have ever captained two different teams to Stanley Cups, winning five with his hometown Oilers and one with the Rangers. (The latter, in 1994, was the Rangers’ first Cup win since 1940 and led to Messier being branded “The Messiah” in New York.)

Now, more than 15 years after retiring from pro hockey, Messier has penned a memoir, No One Wins Alone, which is less autobiography and more rumination on what he learned both as a member and leader of some of hockey’s greatest teams. Here, he discusses memoirs, magic mushrooms, and what makes for a good leader.

You officially retired in 2005. Why write a memoir now? What was your motivation?

It’s a great question. As a player, I was always struck reading Sacred Hoops by Phil Jackson and The Winner Within by Pat Riley. Those are two books that I really enjoyed because they delved into the team aspect of [sport]: the spirituality around a team, the galvanizing of a team, and creating a safe place for players. So I didn’t want to write something just about myself, but instead I wanted to write a book about the experiences that I had, about how beautiful the game — and team sports — can be when you play in a culture that’s conducive to inclusiveness, camaraderie, and winning. And I was lucky enough to have that throughout my [professional hockey career]. Hockey, when you boil it down, is about people; it’s about galvanizing people and maximizing their potential, of course, all through the game of hockey. But in the end, it’s about people. And I think everyone can learn [something] from those lessons.

While hockey was obviously a huge part of your life from an early age, with your dad having a career himself, it never seemed like the game was forced upon you. Is that accurate?

I loved the game because my dad played — and he introduced me to it — but then I fell in love with the game itself. I think, as a parent, it’s always important to understand your child, and my dad had a unique ability to understand when I was being lazy or when I just didn’t want to really go play. There’s a big difference. At times, I was just overwhelmed, and I didn’t really want to go play. And I was never forced to. I mean, that didn’t happen very often, but there were times.

That reminds me of me and my dad. As a little kid, sometimes I’d insist that I wasn’t going to the rink on a Saturday morning for whatever reason. And we’d get into these battles where he didn’t totally understand why I didn’t want to go — I usually had fun — and he’d tell me it was important to follow through on your commitment to a team, which was hard for me to understand at a young age.

Sport can be a great teacher, if you let it. Playing on a team is challenging for a pro, let alone an eight-year-old, because there is accountability. Once you sign up at the start of the year to play on that team, there’s a big responsibility. And if you can force yourself to be accountable, that, to me, is [one of] the most important things we can really do to help our kids through challenging years. And those are the life lessons that stay with kids for the rest of their lives.

“There are so many great young athletes who have never been given the opportunity to play any kind of ice sport. So we’ve got to do more to create access and opportunity, and to diversify the game. We can do better.”

Before the Oilers finally broke through with a Stanley Cup win in 1984, you came up short in the playoffs a handful of times. What did you learn about responding to failure during your career?

If you just look at my own career, having been a part of six Stanley Cup teams, [that means] there are 20 years that I lost. [But] I don’t consider those lost seasons. I consider them steps in the growth of any one player or organization, as long as you’re learning from them and you’re asking yourself questions about, “What did we do right? What did we do wrong? What can we do to be better? How can we evolve as a team? How can we evolve as players, and as people?” Those are the important lessons when things don’t go right.

Is self-reflection an overlooked aspect of being a pro athlete?

Well, I think you have to be interested in growing and becoming a better player, obviously, and you have to be interested in becoming a better teammate and a better, more evolved person. All of these things are important for a championship team because, in the end, you have to surrender yourself for the benefit of the team. And it’s not easy. Most of the time when you get 20 or 22 players on a team, they’re all at different stages of their careers. Some have signed long-term contracts. Others are working towards a contract and might not be happy with the position that they’re in because they’re not going to get the production to get the bigger contract. So working through all of these challenges is part of the process.

In the book, you recount missing a team flight as a young player, which ultimately led to a stint in the minors. You also mention that you liked to enjoy yourself away from the rink and sometimes you took flack for it from the media. One of the challenging things about being a pro athlete, especially a young one, is that there’s an industry built around evaluating you very publicly, and that often goes beyond your on-ice performance to assessing your character. How did you deal with that?

The fact is that, when you become a professional athlete on a professional stage, you do open yourself up to being analyzed, for better or for worse. That’s just part of the game. Of course, there is a certain amount of experience that’s [required] to not get bogged down by what’s being said, negatively or positively, because both can affect you in the wrong way. For me, there were trying times learning the responsibilities of being a pro and understanding that livelihoods were at stake. It’s different being an 18-year-old kid making some money, but families have moved homes and to new cities and new schools. There’s a lot at stake when you play on a professional team, and the decisions that you make directly impact [others]. When you’re hit between the eyes with a sledgehammer that your decisions impact a lot of people, that’s a real “aha moment” for most athletes. And it was for me. It forces you to square up and be accountable and be a good teammate.

You’re a pretty legendary leader, having captained the Oilers and Rangers to Stanley Cups. What are the keys to being a good on-ice leader?

I think, first of all, you have to establish relationships with everybody — interpersonal relationships that go far beyond the game itself. That’s harder and harder now with the amount of [personnel] changes on each team, but it’s critical. You have to establish yourself as someone that’s trustworthy. You have to be consistent in your approach to the game, on and off the ice. You have to be honest; you have to be willing to be honest. You have to be able to give constructive criticism without resentment. And then, of course, you’ve got to lead by example. There’s just so much to that question; it’s so rich with content, becoming and evolving as a leader.

From your vantage point, are those leadership traits as applicable off the ice as they are on?

If you’re dealing with people, it’s all the same. There’s no difference. How do you inspire people? And how do you inspire people to motivate themselves? A leader should never hold themselves responsible for motivating people. That’s a short shelf-life for any leader. A leader’s greatest responsibility is to inspire people. And when you inspire people and you create an amazing workplace and a vision that people believe in, they’ll motivate themselves. And that has longevity. That has legs. That’s how people can coach and mentor and lead people year after year after year. It doesn’t matter if you’re a schoolteacher or a Fortune 500 CEO or factory manager, when you’re dealing with people, the same principles apply.

In the early ’80s, during one off-season, you took a trip to Barbados, where you ended up taking psilocybin, a.k.a. magic mushrooms. And despite thinking that the lizards in your hotel room were dragons, it was a positive experience for you. How so?

I was amazed that something like that could alter and have that big of an effect on my mind. At that point, I was becoming a pro and I was a decent player. I was training and working on my body, and I realized that if the mind is that powerful, how could I train it to do special things at special times under pressure? How can I train my mind as hard as I train my body to be a professional player? And that was an awakening for me. We’d done some power of positive thinking seminars early on, about good self-talk and how important that was, but that particular moment became much more for me than that. It made me more curious about how I could, through the practice of meditation and awareness, become a better player.

Hockey is a difficult sport to access. Equipment is expensive. So is ice time. And that’s true in Canada, let alone a place like Manhattan, where rinks are few and far between. Tell me about your efforts to improve accessibility to the game, as I know that’s something that’s important to you.

We had a feasibility study done not along ago, and to stay up with the national average, we’d have to build 350 rinks in and around the New York Metropolitan Area, and [then we’d] still just be around the national average in terms of access. There are so many great young athletes who have never been given the opportunity to play any kind of ice sport. So we’ve got to do more to create access and opportunity, and to diversify the game. We can do better. And a good start is the Kingsbridge National Ice Center, which we’re trying to create. [It’s] nine sheets of ice, which will have a massive impact on the economy in the area for job creation and for access and opportunity for kids that live in the metropolitan area, especially in the Bronx. It’s been a struggle for all the obvious reasons, but it’s too great a project to give up on.

In retracing your career for this book, is there a singular moment or achievement that stood above the rest?

There are so many great moments — in victory and in loss. So many great moments from a people perspective. So many stories that didn’t make it into the book that were instrumental in my development and evolution as a person and a player. I just look at it as one great big source of gratitude, to be honest with you. And wow, how lucky I have been.