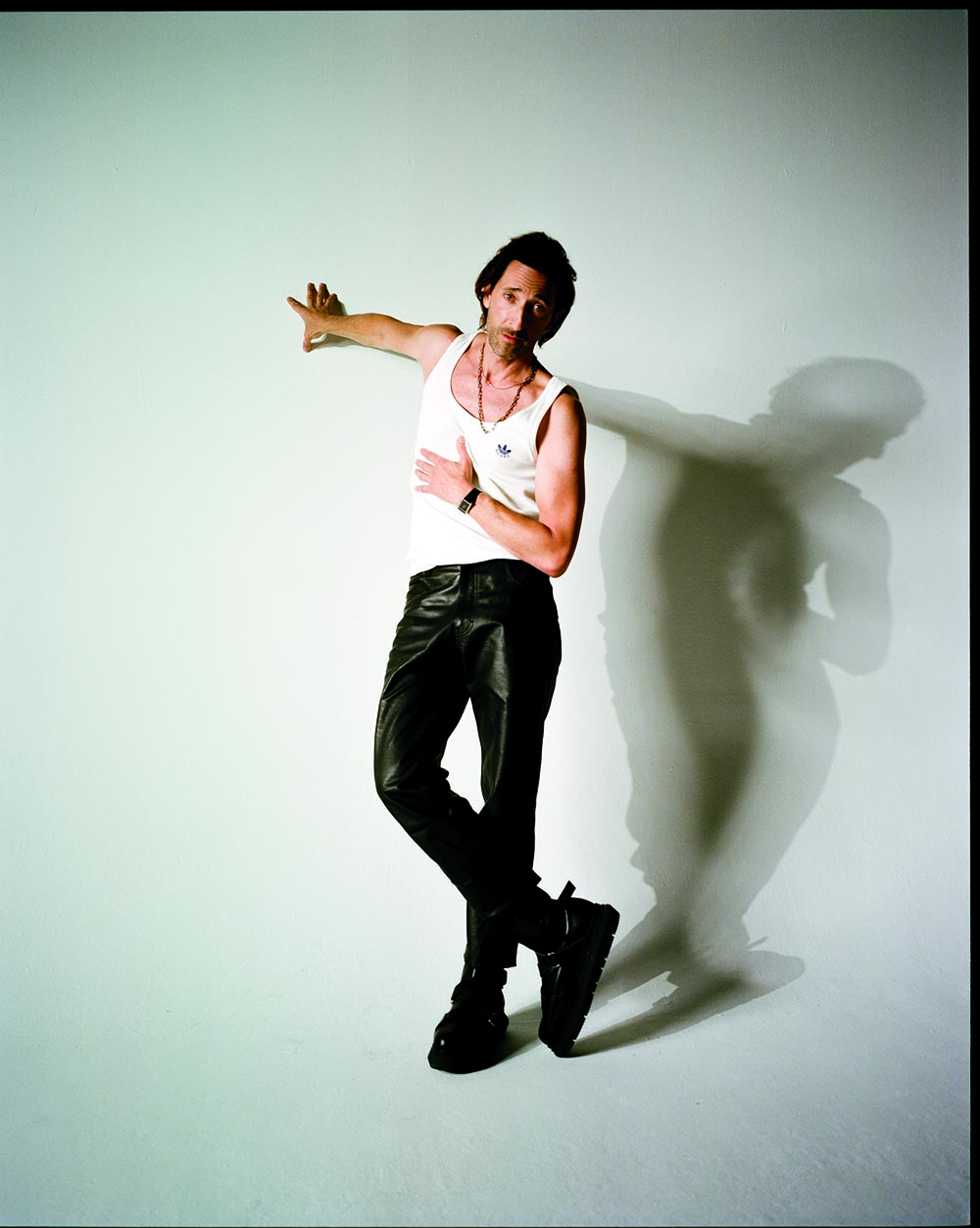

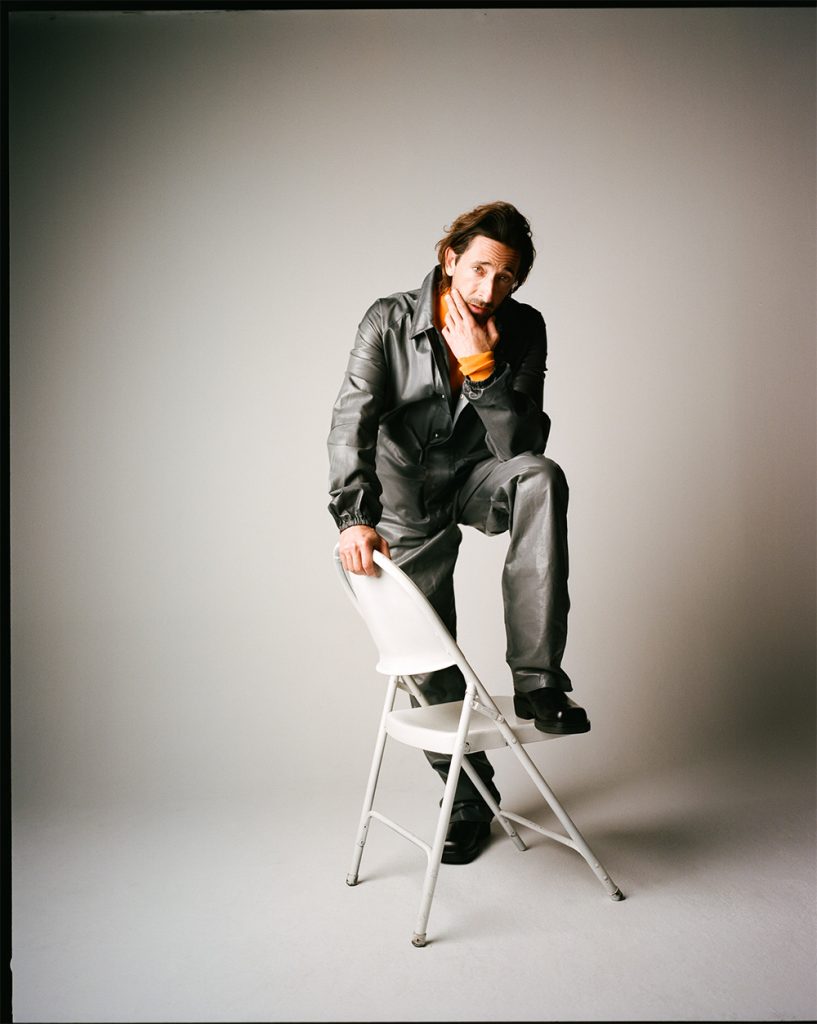

Adrien Brody Keeps Dreaming

Everyone wanted to touch the Oscar.

It was late Sunday evening after the Governors Ball, the glamorous, starstudded gala dinner held every year following the Academy Awards ceremony, and Adrien Brody had to hold on tight to the trophy he’d just won for Best Actor. Everyone was clamouring for it, hovering around as if to absorb some of its glory through osmosis. And the thing was, Brody understood why they were treating it with such spooky reverence. That little gold man seemed like more than just a statue. It seemed like a person.

Brody came home that night with his mother and father to the tiny L.A. guest house he was renting, clutching the Oscar in his hands. “There were three of us in this room,” his mom said, gazing at the statue admiringly. “Now there are four.”

From the present vantage, Brody’s best actor win has a certain feeling of historical inevitability. His performance as Wladyslaw Szpilman, in Roman Polanski’s Holocaust drama The Pianist, was the kind of totalizing star turn whose praise feels almost preordained: he was working under a renowned filmmaker, tackling important subject matter, cloaked in an aura of sober prestige. But it bears emphasizing just how young Brody was at the time of this achievement. 29 years old: not even in his thirties, still the youngest man to ever win that honour.

“It’s funny. Looking back, I really was so young. But I didn’t feel young,” Brody says, talking to me on a recent afternoon from his home in Manhattan. “I had been acting for 17 years already. But for many people, that was their discovery of me as an actor. You know how they say it takes 15 years to become an overnight success? Mine took two years longer.” Winning the Oscar, he explains, was “an overnight shift, frightening and spectacular at the same time.” All the more so because, in career terms, he was still starting out. “You see wonderful actors who have worked for a lifetime and not quite landed that level of recognition,” he says. “The whirlwind of being acknowledged and respected by your peers and the people you grew up admiring is really so moving. For that alone, I am forever grateful.”

Reaching that pinnacle so young might have relieved some pressure. But Brody isn’t one to rest on his laurels. “It doesn’t take away your yearnings to do great work,” he insists. That yearning continues to fuel his creative drive, propelling him through a spate of recent work that is among the finest of his career. He’s been lighting up the small screen with meaty TV parts, like his recent Emmy-nominated turn on Succession and scene-stealing performance as legendary Lakers coach Pat Riley on HBO’s Winning Time. He shepherded a long-time passion project, the dramatic thriller Clean, from conception to release, serving as co-writer, producer, star, and even composer. And he stars as Arthur Miller in one of the toasts of the festival season, Andrew Dominik’s Marilyn Monroe biopic Blonde. Two decades after seizing Oscar glory, he’s still pursuing work that inspires him to be his best.

Brody’s luminous career began auspiciously. In New York City in the mid- 1980s, his father drove him to an open call for child actors at an abandoned factory in a rough part of town, waiting in the car around the corner while the 13-year-old Brody made a go of it inside. The audition – he didn’t even have an agent yet – resulted in a bit part in New York Stories, a three-part anthology drama co-directed by Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese, and Francis Ford Coppola. Brody appeared in the Coppola section, which, as screen debuts go, is a rather high bar. “Well, a high bar as a day player, yes,” he laughs. “But to even work with him for a day was incredible, let alone when I was just starting out.”

The life of an actor is inherently precarious, and for Brody, no early success felt like a guarantee that this career would be sustainable forever. “It wasn’t until The Pianist that I felt like, oh, okay, I might be able to get a job. And even after that I didn’t work for an entire year,” he laughs. Still, his early twenties brought a degree of fortune and stability that any working actor would envy.

He starred in films by Spike Lee (Summer of Sam), Barry Levinson (Liberty Heights), Ken Loach (Bread and Roses), Steven Soderbergh (King of the Hill). “It was such an amazing moment in time, and not something I took for granted,” he says. “During that run I was travelling the world, working with wonderful actors, working with so many diverse directors with such diverse styles of directing. It doesn’t make you assume you’ll get more work, but it sure is encouraging when these people you have tremendous respect for are looking to have you in their project.”

If you find a meaningful role, there should be an enormous

amount of work that goes into it. It should be hell.

Brody’s auteur dalliances of the era culminated in one ultimate art-house opus: The Thin Red Line, from the brilliant, enigmatic director Terrence Malick. Ostensibly a big-budget war epic based on the beloved novel by James Jones, The Thin Red Line marked Malick’s long-awaited return to filmmaking after a more than 20-year absence, during which time his films Badlands and Days of Heaven had become firmly entrenched in the modern American canon. Brody, then still relatively unknown, was cast as Corporal Fife, the novel’s hero, whose story is derived from the author’s wartime experiences; arriving the same year as Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, it was widely expected that the film would be a wrenching, sensational smash.

Whatever audiences expected, The Thin Red Line wasn’t that. Elliptical, sophisticated, almost delicate in its treatment of the horrors of war, the movie is nothing short of a masterpiece, one of the greatest masterpieces of American cinema of the 1990s. The only thing is, Adrien Brody is barely in it.

When Brody showed up with his family to what he was told would be a private screening of the finished film one night in 1998 — it turned out to be a press screening packed with reporters and critics — he was fully expecting to see himself onscreen as the movie’s courageous leading man. He had spent the last 22 months living in the jungle, waking up at four in the morning, enduring brutal humidity and gruelling conditions in a bid for authenticity, but dammit, it would be worth it for the result. But as the movie rolled on, it began to dawn on him what Malick had actually been making. It was an expressionistic snapshot of war. Malick cut to sunlight filtering through trees and insects floating by so often that one critic joked the butterflies had more screentime than Brody.

He didn’t take it in such good humour, at least not initially. “I was there seeing the film for the first time, with no indication that my role had been kind of… well, eviscerated,” Brody laughs, shrugging off what was obviously a painful experience. “We all went downstairs after the screening, and we were just kind of dumbstruck. I had basically been cut out of the movie.” He still winces a bit to think of it. But after a moment, he chuckles again, as if to say, What can you do? “Well. Those things teach you a lot,” he jokes.

You get the sense, talking to Brody about that disappointment, that the wasted effort stings because of how deeply he commits himself to his craft. This is the guy who, in preparing for the role of a ventriloquist in 2002’s Dummy, went out of his way to learn to throw his voice. Taking the job seriously, throwing himself into the mind of a character, is for Brody part and parcel of the work of being a legitimate actor: whatever the part, whatever the movie, the actor has to find a way in, and get in deep. “If you find a meaningful role,” he explains, “there should be an enormous amount of work that goes into it. It should be hell. That’s the pleasure in it.” For this dogged, painstaking approach, Brody credits his parents. “My mother has an incredible work ethic,” he says. “She’s the hardest-working person I know. Her and my father — they instilled that in me from the start.”

Part of the beauty of this work is the opportunity to live all these different lives and go beyond who you are and what you are and how people perceive you.

You can see the results of this industriousness in how substantially Brody inhabits the people he plays on screen. As Pat Riley, on Winning Time, he carries the rock-depth despair of a man beaten and nearly broken by experience; watching him, you can feel the pain vibrating around his body like an aura. (Brody never met Riley in real life, but says he carries his book The Winner Within around with him like a Bible.) Even on Succession — in only two episodes and one really significant scene, among a stacked cast of fan-favourite actors — he manages to stand out with easy gusto, stepping into that world as if he’d always belonged to it.

Brody takes his work so seriously that nothing he’s done should be regarded as somehow beneath consideration. When he starred in Nimrod Antal’s science-fiction action blockbuster Predators, some critics felt he was slumming it. “I did an interview where the journalist was so surprised I had taken that role, and looked upon it like, ‘Why would you do that?’ He had a real preconceived idea of why I must have had to do it. That was totally incorrect.” What people like that don’t understand, Brody says, “is that part of the beauty of this work is the opportunity to live all these different lives and go beyond who you are and what you are and how people perceive you,” whether that’s as a piano player during the Holocaust or a soldier fighting aliens in outer space. Besides which, landing Predators was no small feat in the first place. “That role wasn’t presented to me. It was a challenge to get,” he laughs.

The shoot-em-up action of Predators was followed by a string of critically acclaimed indie hits that found Brody working once again with vaunted auteurs. These included Detachment, a raw classroom drama about a substitute teacher at a troubled inner-city school, from famously volatile American History X director Tony Kaye; Midnight in Paris, Woody Allen’s charming tale of golden-age nostalgia, in which Brody appears in a single scene as Salvador Dali and roundly steals the entire show; and The Grand Budapest Hotel, the Stefan Zweig-inspired comic epic that reunited Brody with the great Wes Anderson, with whom he made 2007’s picaresque The Darjeeling Limited. (In Brody, you feel, Anderson found an irresistible muse: they continued their creative collaboration last year with The French Dispatch.)

His recent work has found him pushing further and further, exploring the outer limits of what he’s capable of doing. In taking the reins on Clean, he was trying things he’d never thought to attempt before, controlling a production from the top down with the devotion of someone who desperately wants the project to see the light of day. “More than anything I’ve ever worked on, that was a passion project,” he says. “We made that movie from scratch. It was built from the ground up, and held up through tremendously difficult times, and managed to find an audience. I’m relieved and grateful for that. It was another level of creative exploration that I had been longing to do, yearning to do.”

For Brody, few qualities are more important to his life and to his work than being receptive — receptive to what life presents you, what opportunities arise and what paths are there for you to follow. “I feel like there are these opportunities that can come once in a lifetime, and you have to be ready for those opportunities and prepared to do the work that they require,” he reflects. Whether it’s being offered a role in a difficult-sounding Roman Polanski film or taking on writing and producing duties on a thriller, or simply finding another remarkable role, Brody will always remain ready and willing.

“You have to be open. It’s a very rare thing — you can’t take it for granted, any aspect of it,” he says. “That’s something that I, long story short, am very attuned to, both in life and in the work that is so much a part of my life.”

Photography: Akram Shah

Styling: Anna Su (Art Department)

Grooming: Jessica Ortiz using BOY DE CHANEL (Kalpana NYC)

Photo Assistant: Muhanad Alothman

Stylist Assistant: Anna Reece

Producer: Haley Bolen (Hyperion.LA)