Guy Pearce on Playing Infamous KGB Mole Kim Philby in ‘A Spy Among Friends’

What drives a person to betray their country and closest compatriots? That’s the question at the heart of A Spy Among Friends, the latest from Homeland writer/producer Alexander Cary.

Based on Ben Macintyre’s bestseller, the mini-series attempts to answer that via a forensic analysis of the friendship between two men: MI6 agent Nicholas Elliott (Damian Lewis) and Kim Philby (Guy Pearce), who famously infiltrated the highest levels of British intelligence while working for the KGB as part of the so-called “Cambridge Five” spy ring.

Much has been written about Philby since he defected to Moscow in 1963, giving Elliott the slip following four days of cat-and-mouse in a Beirut safe house. Whether you already know the story or not, the rakish, high-society double agent helped inspire much of modern spy fiction as we know it. John le Carré famously used Philby as the basis for his “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” traitor. (Then-MI5 agent Ian Fleming even makes a brief appearance in the show’s Episode Two.)

Yet here we are some 60 years later, and Philby’s motivations remain shrouded in mystery. It’s not a question Pearce expected to definitively solve in the six-hour mini-series. “There have been scholars who haven’t managed to articulate and understand,” he laughs. “Let alone an actor from Geelong.” Still, Pearce enjoyed getting to play a character who was perpetually playing a part, even around his closest friends.

With A Spy Among Friends now streaming on Prime Video, we spoke to Pearce about what he thinks drove Philby, why we’re so enduringly fascinated by spy stories, and what double agents and thespians have in common.

How much did you know about Kim Philby and the Cambridge Five going into this?

I knew a little bit. I didn’t really know anything about the relationship between [Philby and Elliott]. In fact, I didn’t know anything about Nicholas Elliott before, but I was aware of the Cambridge Five. I’d seen a couple of films and maybe a doco or two spread over the years. I was born just outside of Cambridge, so I suppose on some little level I went, “Oh, fascinating.” But I didn’t really know a great deal other than the fact that there were these five English spies who were double agents.

Once I signed on to this, I delved into and discovered a lot more, and understood a lot more about Philby particularly and what went on. And it only became more and more fascinating to me, just to the point where almost every day I was saying to myself, I cannot believe he did this. I just cannot believe that he did this, and he got away with it. It’s just incredible.

Are you a big researcher when you’re prepping for a part like this?

I delve into everything I can find, but there sort of comes a point where I go, “Oh, enough, enough, enough.” I’m forgetting what it is I’m doing, and I’m just indulging because it’s fascinating. You’ve got to be careful.

But usually what I do is wade my way through everything I can find. Documentaries and books and audio recordings and interviews, and there’ll be some little clincher or two that helps me understand the person I’m playing. But particularly with a character like this who’s quite mysterious, the whole point is that he’s two-faced, so you don’t quite know who you’re getting at any one time. We want the private moments, and we want the moments where he’s playing somebody else in front of other people.

If you’ve got somebody who is able to thread both — and he was very charming and was quite the cad — you can’t help but be intoxicated by people like that.

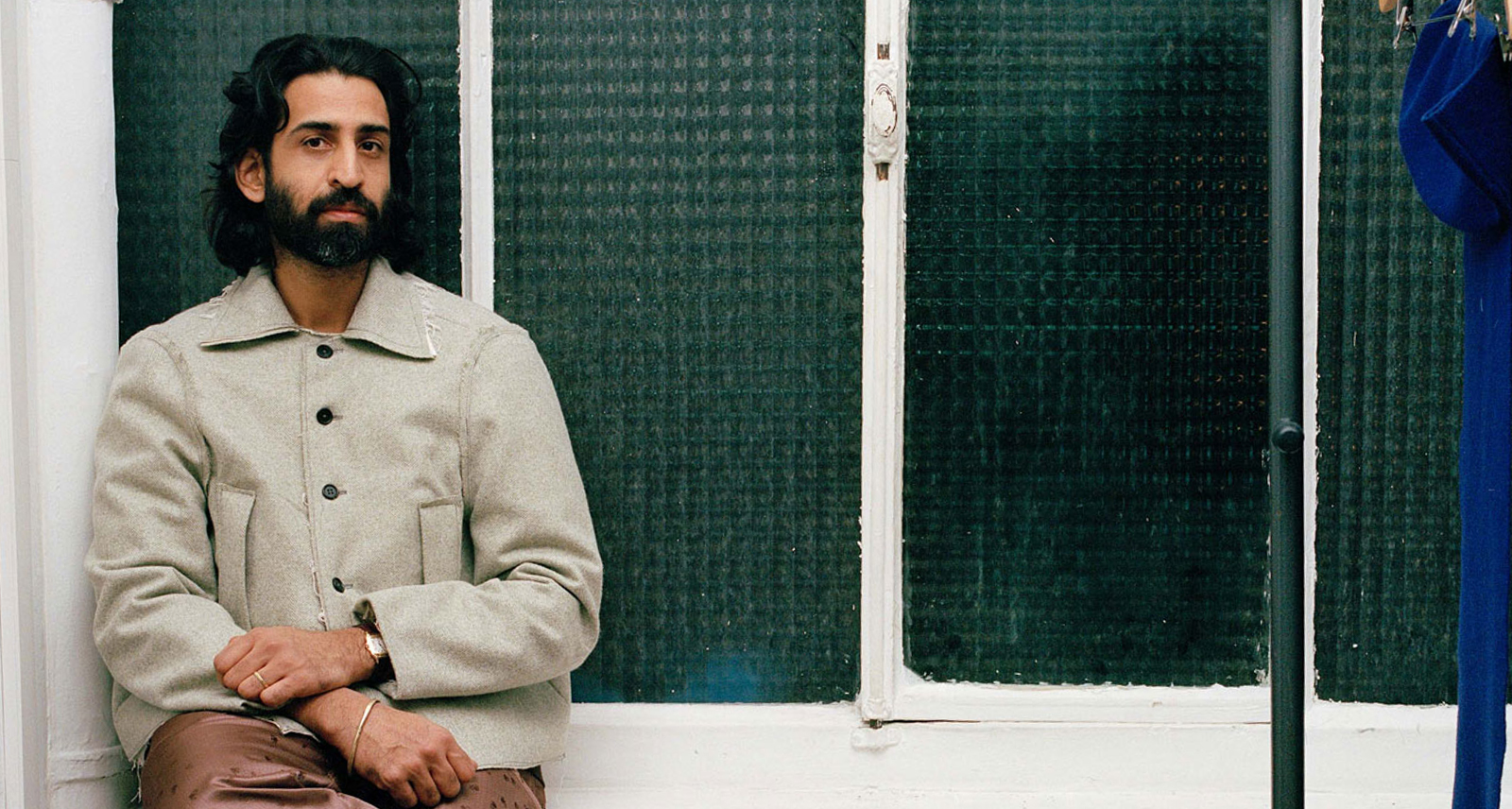

Guy Pearce

But yeah, there was a lot to wade through. I found the book that his American wife, Eleanor, wrote. She was the one he was with when he left Beirut. Their time together — from him leaving, to her then joining him, and her year or year and a half in Moscow before they split — that period, she wrote a book about, and [included] letters back and forth between them. That was the thing that I felt gave me the truest sense of who he was.

It makes sense, because I know Philby wrote a memoir, but he’s not exactly the most reliable narrator.

That’s right. In her book, there are letters from him to her. Now, his letters may also be dubious, but I feel like they’re probably less dubious than a book he’s going to write.

Were you able to pull anything from those for your performance?

Just the vulnerability. The fact that inside this man who was playing everyone was a genuine, vulnerable human being. I had to make sense somehow of his continual claim that he believed in communist ideals, had believed in communism and had done so since he was 20. This idealistic view that he had at the time, why he maintained — or claimed that he maintained — that belief throughout his life.

I think it was partly that [which drove Philby], but I think it was also partly that he had a disdain for the British ruling class that he was brought up in. I do think there was a part of him that was going “Fuck you” to that, and using the beliefs in communism to justify it. But he was having his cake and eating it too. So everything’s kind of questionable, I reckon.

I have to assume also that the intoxication of getting away with something early on, and then more, and then more, and then more… It’s far more exciting to be a double agent than to just be a spy for one country, right? So, I imagine there’s a lot of ego going on in there. And he did it for 30 odd years.

This show does leave that question fairly open-ended: how much Philby was driven by ideology versus ego. It sounds like it wasn’t super important for you to have a firm, definite answer to that in your head?

I think he’s got feet in both camps. I don’t think the show sets out to go, “Aha, this is the final say on who Philby really was.” Because the reality is, no one’s ever going to be able to really say that anyway.

It speaks to, I suppose, our ability to be manipulative, to be powerful, to lose power, to be vulnerable. Just to be a multitude of psychological aspects. And this man was able to just dish them out at will, it seemed like.

The “gentleman spy” has very much become its own specific archetype, partly thanks to real-life stories like Philby and the Cambridge Five. Why do you think we’re so enduringly fascinated by characters like this, even six decades later?

I think that we’re interested in crime. We’re interested in characters who break the law, and why they do it. And we’re also interested in characters who break the law that we still feel something for, even once they’ve done that. How they can manage to still be appealing, or we can have sympathy for them, even if they’ve done horrible things.

Because we do want to always pigeonhole people and go, “Is he a bad guy, or a good guy?” If you’ve got somebody who is able to thread both — and he was very charming and was quite the cad — you can’t help but be intoxicated by people like that. There’s just something… I suppose we want to be like that, in a way.

Watching this, I was struck by the similarities between what it takes to be a successful spy and what it takes to be a successful actor. It does feel like there’s overlap.

Well, there’s certainly acting involved in their job. I mean, there’s acting involved in everybody’s jobs in a way. But there’s definitely life-and-death acting involved in that of a spy, and that of an undercover cop. It brings you to the question of why we are able to act, why we have this ability to say one thing and mean something else.

… the thing about playing drunk is that drunks are trying to act sober.

Guy Pearce

Some people would say, well, it’s just lying. That’s all there is to it. And the Dalai Lama would say, you’ve got to fake it until you make it. If you want to be a good person in life, you’ve got to start acting like a good person, and then you will develop into that person. So is that lying, or is that being malleable and shaping yourself to being who you want to be? That skill or that ability, and that desire and that drive, I think is in everybody.

The funny thing is, I think, for Philby, who really did have disdain for the British ruling class, and disdain for the fact that just because you went to Eton or Oxford or Cambridge, that MI6 was going to say, “You’re our people, come on in.” They don’t really do their homework, and Philby’s going, “You’re fucking idiots for not doing your homework.” I mean, he’d married a communist years beforehand. And that didn’t ring any alarm bells for those at MI6. [Laughs.] So he was like, well, if you’re going to be that blind, then it’s your own silly fault for letting me get through the system.

Funnily enough, I remember somebody saying to me years ago, the thing about playing drunk is that drunks are trying to act sober. We think we’ve got to play someone drunk like [slurring] and then you start to wobble. But most drunks are going, [sits up straight] “No, no. I’m sober.” So just that in itself is a good 101 lesson in playing drunk.

That wasn’t your background growing up though, right? I know Damian Lewis and Alex Cary both went to British private schools.

I went to a private school in Australia that was modeled very much [after that].

Oh, really?

I mean, it was Australian, so it was a bit more loose… But we were trussed up with ties and all that stuff, and I hated it. The thing is, I really get it in a way, because there I was at this private school where we were meant to be considered fortunate, because we were having the best education. And yet I hated a lot about it.

And I was being creative and making music and making art and doing all that, and everyone else was rowing and wanting to be doctors and lawyers, and I was going, I don’t fit into this at all. So, in a way, I immediately understood Philby, to a degree. I understood that aspect of Philby. Much more extreme, obviously, in Philby’s case. But I got a taste of it, so I kind of got it.

The series touches on Kim’s alcoholism and heavy drinking, which seems so antithetical to being a successful spy. I will say you do a very good drunk here, which I’ve always been impressed by, when someone can make that feel authentic. Are there any keys to giving a credible drunk performance in your mind?

The thing about Philby was, and I think people in those days — you look at a show like Mad Men where 11 in the morning, they’re all having a little scotch, and just having a couple of scotches throughout the day — they just function on this low-grade drunk. They’re not that drunk, but Philby clearly could put them away. And I think his comeuppance or punishment in the end was that he did drink himself to death. His internal demons in regard to what he’d done got to him. And I think the only way for him to deal with that was just to keep on drinking.

He ended up in Moscow, and he didn’t really want to be there, and I think was disillusioned by the world there. So to watch this man who had been the life of the party, had been very charming, had been very dapper, become this broken, decrepit, slightly maudlin character was great to play. Just to watch that slow sliding down the hill through the mud until he’s at the bottom going, “No, no, I am still who I am!”

But he never accidently blew his cover, which is impressive.

That’s a skill in itself. Making sure that all the other people that he’s talking to are just as drunk as he is. [Laughs.] “You’re just as drunk as me! So I can actually say that I’m spying for the Russians, and you’re never going to believe it. Ha ha, it’s a wonderful joke, you know.”

‘A Spy Among Friends’ is now streaming on Prime Video.