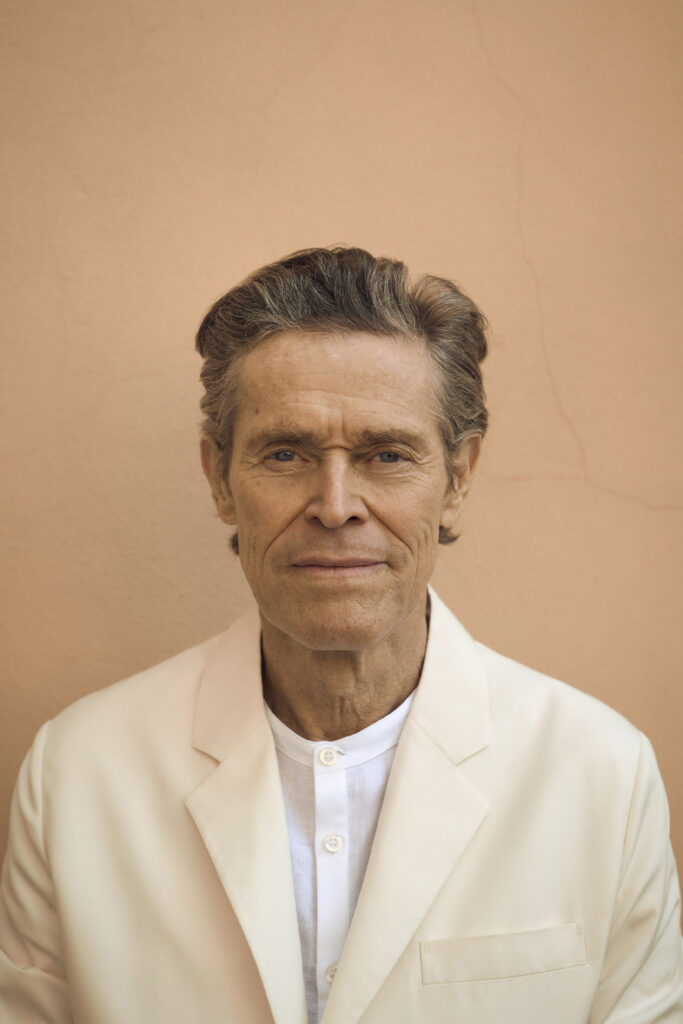

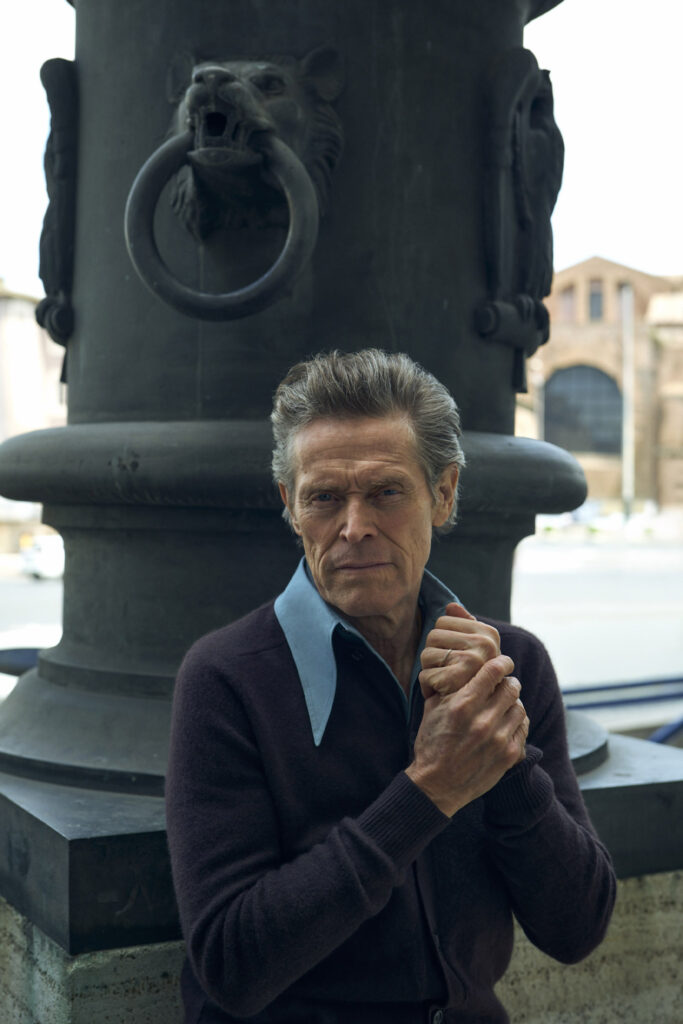

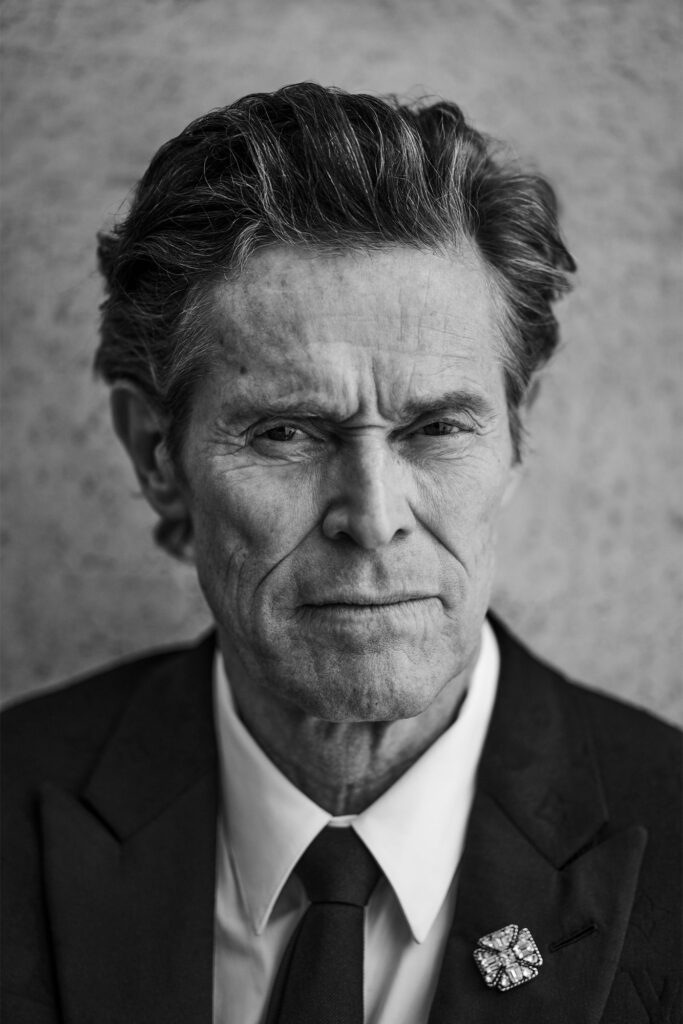

Willem Dafoe Isn’t a Movie Star; He’s a Character Chameleon

“You hate to repeat yourself,” Willem Dafoe says in his distinct gravelly voice — instantly recognizable from any number of projects, but with a gracious tone that’s all his own.

Speaking over the phone from Rome on a Sunday afternoon shooting break, the four-time Academy Award nominee sounds amiable and reflective, looking ahead to an impressive number of releases in the next year or so, including a brief role this summer in Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City, his fifth project with the director, as well as key parts in Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things and Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu up ahead.

“It’s not as a show of versatility, so much as you want to learn something, you want to have an adventure, you want to go forward and do something different.”

Willem Dafoe

Dafoe has taken on some of the most varied projects imaginable, from Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) and Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini (2014) to the Marvel box office behemoth Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021) But for him, the range itself is not the point. “It’s not as a show of versatility,” he says, “so much as you want to learn something, you want to have an adventure, you want to go forward and do something different.”

Impossible to typecast despite having played a number of the sorts of roles that might have gotten stuck in both filmmakers’ and critics’ minds — including the bestial but vulnerable Max Schreck in Shadow of the Vampire (2000), the character actor as monster, and a decidedly fallible Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) — Dafoe attributes his malleability not to any concerted effort on his part to break the mould but to his instinct for choosing projects and characters that excite him. “I’m not a guy who wants to cart out the things that he knows,” he says. “I want on-the-job training.”

Over the course of a more than 40-year career that began in experimental theatre in New York, where he was a founding member of the Wooster Group, Dafoe has had plenty of training in different lines of work, from painting to filmmaking to counselling to armed robbery. He’s become cherished for his ability to maintain his iconicity while confidently slipping into the skin of virtually any kind of person, his unique physicality and striking screen presence always neatly folding into the task at hand.

Early in his career, though, some seemed eager to channel Dafoe’s idiosyncratic presence into volatile, sexually charged, dangerous characters — at a minimum, men you wouldn’t trust to watch your bag, if not outright villains. When we first see him in his debut screen appearance as a moody motorcycle hunk in Kathryn Bigelow and Monty Montgomery’s The Loveless (1982), for instance, the camera tilts up to take in his lithe body, intense grey eyes, and striking cheekbones. His leather-jacket adorned figure was the very picture of the motorcycle greaser bad boy, as he combed back his perfectly slicked hair as if he knew we’re looking at him. The camera loved his smouldering strangeness from the start.

“I admire movie stars in the respect that sometimes they find a persona and then they work in projects that support that persona […] But I’ve jumped around. I don’t cling to a certain way that I want to be.”

Willem Dafoe

Dafoe is reflective about whether his unique appearance was a help or a hindrance early on. “In the beginning,” he says, “I was much more fearful of typecasting, afraid of being limited in how you could be seen and what you could do.” As for his intimidating presence as sinewy, magnetic antagonists in early films such as Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) and William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), he insists that he hasn’t become any less physical over the years: “It’s just my nature, and also my background in the theatre, which is and was a very physical kind of theatre,” he laughs.

But he concedes it’s true that he had to fight against people holding his early roles against him. “When you start out,” he tells me, “if you aren’t conventionally handsome or attractive in a very recognizable way, the best roles are character roles. And the best character roles for a young man are usually villains. But after I’d done some films and I saw people seeing me a certain way, I was conscious that I didn’t want to lock that down as a stamp. I have no stake in being versatile. It’s just that personally, I don’t want to be called to do that thing that I do.”

His reputation for being unfailingly original has boosted the profile of any number of small independent films, several of which he’s carried to Oscar nominations. But Dafoe insists that he has always aspired to be an actor qua actor, who can move in and out of different roles, rather than a movie star, from whom audiences expect a certain kind of performance. “I admire movie stars in the respect that sometimes they find a persona and then they work in projects that support that persona,” he says, admitting that a star in the right project “can be a very beautiful thing to watch. But I’ve jumped around. I don’t cling to a certain way that I want to be.”

That bears out in the capaciousness and versatility of his screen work. For all his prowess as a villain, Dafoe is also one of the finest actors we have at portraying a kind of troubled decency. We see it not just in his performance as Scorsese’s Jesus, who dreams of deferring his call to die as the Messiah to live as a man, but also in his doomed Sergeant Elias in Platoon — a doting mother hen to his young infantrymen, teaching them which gear they need to carry to survive, and which they can discard to move lighter on their feet — as well as his basically kind but morally compromised drug dealer in Light Sleeper.

“We’re all a little bad, we’re all a little good, and the proportions vary in each person. It’s always fun to find the sweetness in a bad guy and find the darkness in a good guy.”

Willem Dafoe

It’s especially pronounced in his Academy Award-nominated turn in The Florida Project (2017). Warm and gregarious — and like Dafoe, quick to laugh — his budget motel manager Bobby in Sean Baker’s film is not just an administrator and a handyman but an unofficial social worker for the precariously housed residents who come through his doors.

“I want to be that person sometimes,” he says of generous characters who make sacrifices for others. “It’s fun to play on evil impulses because you don’t do them in life. But when you think about the function of telling stories, it’s nice when you feel like you’re putting something positive forward that can inspire people to say, ‘I’ve got to be kinder.’ That sounds kind of Pollyanna, but in movies, the thing that gets me always is kindness.”

That doesn’t mean it isn’t pleasurable to play characters bending their morals to get their way. “Nobody’s just one thing,” he says. “We’re all a little bad, we’re all a little good, and the proportions vary in each person. It’s always fun to find the sweetness in a bad guy and find the darkness in a good guy. That almost goes without saying. But sometimes it’s a little hard to practice.”

“When you’re physically engaged, there’s a greater chance of getting in the groove because if you get too much in your head, you start creating certain kinds of expectations and ironically, limitations. You can overthink things.”

Willem Dafoe

Practice is important to Dafoe, for whom the basis of all acting is doing things rather than emoting: “It’s about listening, it’s about moving, it’s about rhythm, it’s about music.” That action starts with anchoring himself in the skin and bones of his characters. “It always starts with the physical and it ends with the physical,” he says of the appeal of wire-work and action-heavy projects like his role as Norman Osborn in the Spider-Man films. “When you’re physically engaged, there’s a greater chance of getting in the groove because if you get too much in your head, you start creating certain kinds of expectations and ironically, limitations. You can overthink things.”

Unsurprisingly for an actor who has given some of his best performances as tactile men who create (or steal) things with their hands — including his counterfeit money-maker and painter Eric Masters in Friedkin’s film or Vincent Van Gogh in Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate (2018), for which he received his fourth Oscar nomination and his first as a leading man — Dafoe appreciates concreteness. He lights up when speaking of costumes and makeup as tools for getting out of one’s own head and into the character’s, calling them “triggers for pretend.” Gesturing to his dissipated appearance as the compulsively violent career criminal Bobby Peru in David Lynch’s Wild At Heart (1990), he credits the first time he popped the character’s dentures into his mouth for helping him find the character.

“When I put those rotten teeth in my mouth, I couldn’t close my mouth,” he says. “And if you keep your mouth open all the time, mouth-breathing, it gives you a feeling of sleaziness, a kind of lasciviousness. That was a huge key to the character.” Costumes and makeup choices like the bushy beard and pipe sported by his haggard lighthouse keeper Thomas in The Lighthouse (2019) or his red beanie and baby blue shorts as Klaus in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), he says, “make the world, and you get behind them. Sometimes they trigger something in your imagination or from your childhood. Rather than designing those things emotionally, you’re presented with something that just forces you to be a certain way.”

Where some actors revel in burrowing into the psychology and emotional depths of their characters before shooting, Dafoe speaks often of the pleasure of being forced into his characters’ behaviour by these concrete signifiers of who they are and what they do, which he attributes largely to the imagination and clarity of filmmakers who know what they want. In recent years, Dafoe has worked with a host of emerging auteurs like Eggers and Baker — both of whom he’s said he expressly pursued for projects — and stylists like Yorgos Lanthimos in the upcoming Poor Things, as well as a stable of regular collaborators such as Schnabel, Ferrara, Anderson, and Lars Von Trier.

“The actual doing is such a pleasure and such a gift. It’s a good life.”

Willem Dafoe

“I feel like the best directors are the ones that make a world that is so complete,” he says of his penchant for alternating between new colleagues and old favourites, “that you enter it, and it becomes very clear what you need to do. And the pleasure is in doing it and seeing what happens and taking it to some place that you couldn’t imagine.” As frustrating as the business can be, he attests, working with directors with an intelligible vision is a joy, akin to becoming a soldier in their struggle. “The actual doing is such a pleasure and such a gift. It’s a good life.”

Life is best, though, when the roles require a lot of him. Dafoe appreciates small parts where he feels he might have something to contribute, or where it gets him in the door working with a director he admires, but they’re not what sustains him; they can’t compare, he says, to the expansiveness of roles that ask more from him. “You can more deeply pretend when you’ve got a more central role,” he says.

This position is borne out by the specificity and generosity with which, on the eve of his small role in Asteroid City, he remembers his time working on The Life Aquatic, his largest role for Anderson, which he describes as a more improvised working experience than his other collaborations with the famously aesthetically rigorous filmmaker.

“He had that same kind of meticulousness and control and clarity,” he says of their first time working together, “But as far as the actual dialogue and the character, he was a little looser. That was fun because there was room for me to fold into it. There would be a shot where he would say, ‘Willem, go in there.’ I wasn’t written in that scene, but he’d put me in, and then we’d create something. Life Aquatic is dear to me.”

Dafoe also cherishes his collaborations with Ferrara, whose emotionally unvarnished, nakedly autobiographical, devil-may-care approach looks diametrically opposed, at least from the outside to Anderson’s fastidiousness. Their work together has taken on a more personal, intimate tone starting with 2011’s 4:44 Last Day on Earth, a tender chamber piece about domesticity, love, and old habits at the end of the world. “I love that he’s a self-starter,” he says of Ferrara. “I love that he doesn’t wait. I love that he’s passionate. He lives through film. Something like Tommaso (2019) is a totally improvised movie, with maybe an exception of a couple of written scenes. And he just basically whispers into my ear what he sees, and then we try to do it.” A loyal soldier in Ferrara’s creative struggle, per his own war metaphor, Dafoe speaks of doing a kind of service to filmmakers like him, with whom he has a shorthand and a history. “There’s a bond there,” he says, “and when he needs me to do something, I’m happy to be there because I like being part of his story. I think that’s true for all directors that I’ve worked with more than once. I like being part of the texture of their work.”

“Relax for a little bit, and then find another mission, find another family, find another collaboration, find another thing to make.”

Willem Dafoe

For all his desire to move forward rather than fall back on old roles or old skill sets, Dafoe admits that leaving behind such memorable tours of duty and returning to the actorly equivalent of civilian life can be melancholy. “I just wrapped Nosferatu,” he tells me, “and I was reflecting on how no matter how many films that I’ve done, finishing one is always bittersweet because you’re like a man without a country. You’ve had a mission, you’ve had this collaboration that you’ve been invited into, and sometimes it’s in a very exotic place, or a place where you aren’t comfortable, and you’ve got to find a way to get comfortable. You get taken away from your life and you have this parallel life for a period of time, and you dedicate yourself to it and something happens. And then you finish your work and you’re like, wow, what was that?”

Yet he sounds awfully well-adjusted and good-tempered for a man with so many parallel lives — tickled by the possibility that he’ll get to live another life soon. “It’s a very strange feeling,” he says of the mournful period immediately after closing shop on a project he’s given his all on for weeks or months. “But after a while, you have it enough that you recognize that it’s not going to kill you.” Not a workaholic but an adventurer, Dafoe is always on the lookout for what’s next, driven by an internal voice that motivates him out of that initial bittersweet lull to think about the next chapter. “Relax for a little bit,” it tells him, “and then find another mission, find another family, find another collaboration, find another thing to make.”

Photography: Charlie Gray (LGA Management)

Styling: Jay Hines (The Only Agency)

Grooming: Brady Lea at Premier Hair & Make-up using Shakeup Cosmetics

Hair: Sam McKnight

Stylist Assistant: Marzia Cipolla

Photo Assistant: Samuele Donnini

Producer: Simona Silvano

Feature Photo Look: Prada

Shot on location at Anantara Palazzo Naiadi Rome.