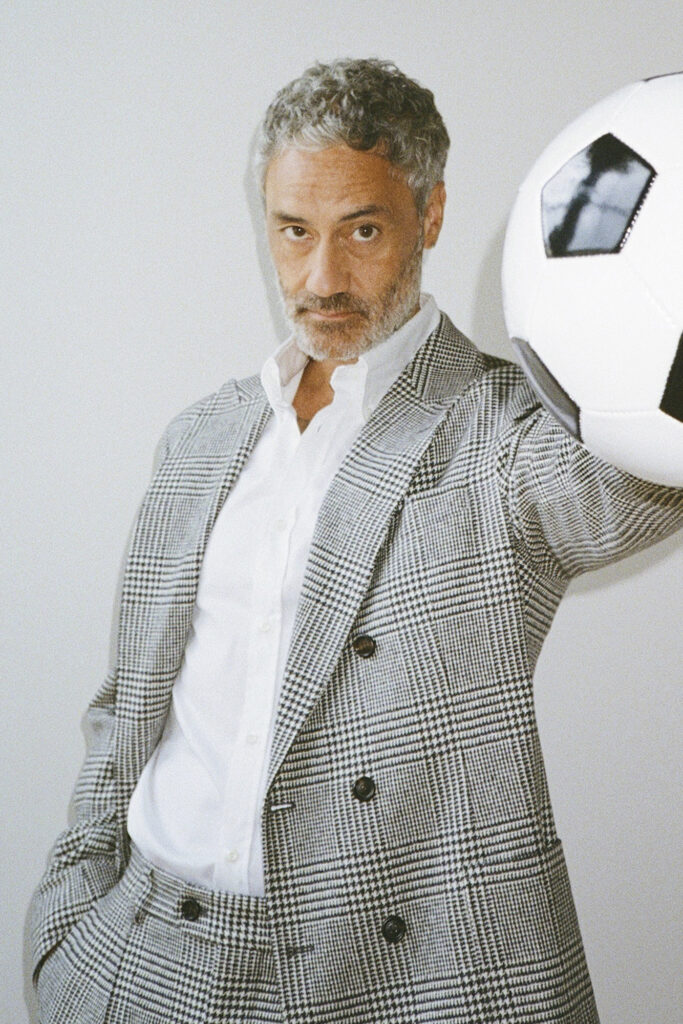

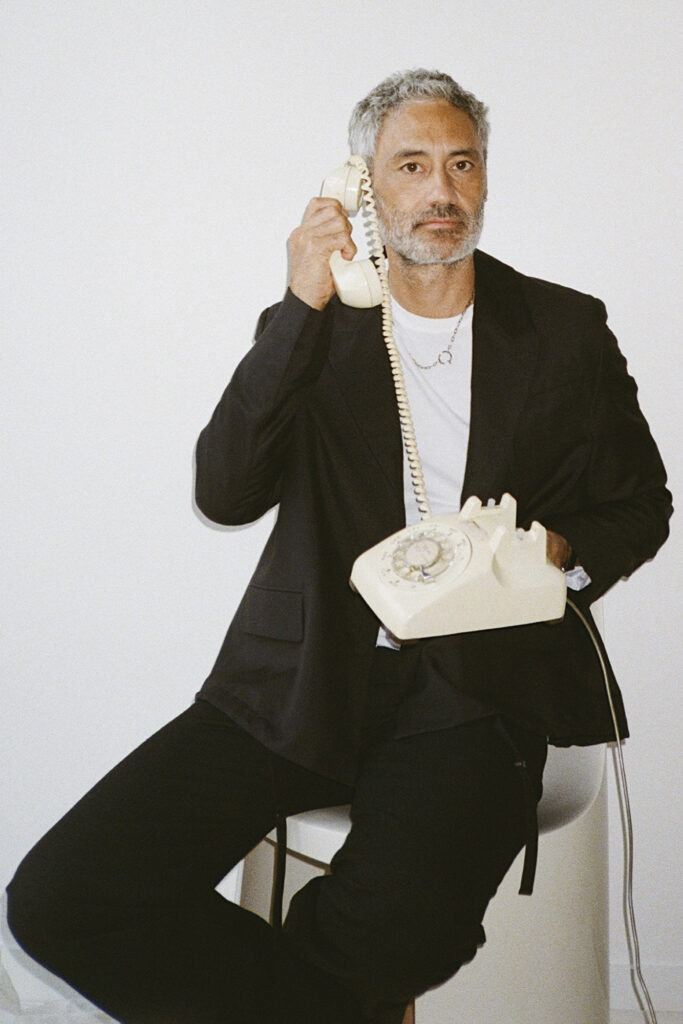

With ‘Next Goals Wins,’ Taika Waititi Wants You to Feel Good

A little under a century ago, Georgian psychologist Dimitri Uznadze published an academic paper. It was a study of sounds and symbolism, outlining a theory he christened “the bouba/ kiki effect.” The idea, as proposed by Uznadze, was that humans are hard-wired to associate specific words and sounds with certain shapes. “Bouba,” he said, should call to mind soft, round shapes, while those conjured up by “kiki” tend to be sharper, spikier.

By the late 1920s, German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler had taken Uznadze’s research one step further. Using two new nonsense words — “maluma” and “takete” — Köhler claimed such triggers run deeper than simple shape association, and can actually affect and alter our moods. “Maluma,” he said, was happy, a heartwarming hug of a word. But “takete”? A jarring and jagged sound — likely to evoke feelings of upset, anxiety, and pain.

So what gives? Because every film directed by our latest cover star — an actor, director, writer, and proud New Zealander — is a “maluma” movie. His are as “bouba” a bunch of flicks as a filmmaker could possibly muster; balms of films that range from soul-stirring superhero fare to disarming romantic comedies. There are no dark and stormy nights in their runtimes, nor tortured souls in their scripts. How strange, then, that each of these feel-good titles sprang from the mind of the same individual — a man who, in Hollywood’s long history, has perhaps the most “takete” and “kiki” name of them all.

“Well, I’m a feel-good guy,” says Taika Waititi. “But I don’t think the ‘feel-goodness’ of it all is necessarily unique to me — although it certainly feels as though it’s getting rarer in films. There are a lot of auteurs these days where it’s like: I’ve got to punish audiences for spending $25 to come and see my vision! We must make them feel terrible!”

“I think it’s okay to feel good. And I think, more and more nowadays, audiences need to be reminded that life actually is good, and that humans are actually intrinsically good people.”

Taika Waititi

Waititi, on the other hand, has always seen cinema as something optimistic. Growing up in a poor area of New Zealand, where he was born to an Ashkenazi mother and Maori father, movie theatres offered the future filmmaker an escape, a place where his spirits could be lifted. And the moments he remembers most fondly, he says, are those of air-punching, whoop-inducing glee — epitomized, for Waititi at least, by the moment Daniel LaRusso crane-kicks Johnny Lawrence at the end of The Karate Kid.

“It’s the triumph of the underdog,” explains the director. “It’s when E.T. comes back to life. It’s the moment Marty McFly’s parents kiss. It’s those moments that are uplifting and make the audience cheer. Look, I love a good depressing European film just as much as the next guy, but I don’t want to watch them all the time. And I quickly let go of them when I do. I think it’s okay to feel good. And I think, more and more nowadays, audiences need to be reminded that life actually is good, and that humans are actually intrinsically good people.”

To that end, Waititi’s latest film ticks every upbeat box. In theatres Nov. 17, Next Goal Wins may be the 48-year-old filmmaker’s first sports movie, but it’s as wholesome as the rest — stuffed with happy-go-lucky chuckles and bearing no barbs upon which moviegoers might be snagged. It tells the true-life tale of the American Samoa national football team which, in 2001, suffered the most land-sliding, laugh-and-point loss in FIFA history. A 2014 documentary detailed the fallout from the game (in which the Australian national team defeated American Samoa by 31 goals to nil at a World Cup qualifier) and Waititi was so inspired by the story that he started work on an adaptation.

SHARP caught up with the filmmaker twice in the run-up to the movie’s release, first to photograph him in downtown Toronto when the footballing film premiered at TIFF, and again today, when Waititi once more finds himself pitch-side — albeit for a different sport. The New Zealander is in Paris, primed to watch his native All Blacks give Argentina a thrashing in the Rugby World Cup. He calls this “the real football,” and stands by a candid claim he made on Instagram earlier this year that soccer was “a sport [he knows] nothing about.”

Major League Soccer may be attracting ever bigger names, he admits, Ryan Reynolds may have staged a well-publicized takeover of Welsh club Wrexham, and Ted Lasso may have become a global hit (although Waititi hasn’t seen a single episode of the Apple TV+ show), but the filmmaker maintains his indifference. He married British pop star Rita Ora last summer, which has seen him spend more time in the U.K. of late, but even the world-leading lure of the Premier League has failed to entice him.

“I wouldn’t know where to begin!” he laughs. “It’s like when someone says you should start watching The Wire. I don’t have time for that!”

“There’s no written word for us [Pacific Islanders]. So, it’s all about telling stories, and retelling stories again and again — and embellishing them more and more until they become mythology.

Taika Waititi

The same Instagram post saw Waititi label Next Goal Wins his “least cynical film.” “Nothing really bad happens,” he explains, “and it’s probably the most joyful film I’ve made. My other films have fallen into a pattern, where something tragic must happen to remind the audience that the world is a fucked-up place and terrible shit happens to people all the time. For me, especially now, I feel like we get reminded of that enough every day. And I think it’s okay to just make some cinema where it’s nice, and all about happiness and hope.”

On the praise-heaped heels of Jojo Rabbit, but before he rolled the cameras on Thor: Love and Thunder (Waititi previously directed the third entry in the superhero franchise, Ragnarok), the filmmaker was keen to revisit his roots. From his feature debut, Eagle vs Shark, in 2007, to 2016’s Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Waititi had filmed the first four movies of his career entirely in New Zealand. “So, when I watched the documentary Next Goal Wins, he says, “it not only had so many elements of great sports films, but it was made extra special because it was about Polynesians, and that was a chance for me to come back home, to do something in my neck of the woods.”

The film ended up shooting in Hawaii, but it retains the spirit of the acclaimed 2014 documentary, which follows the efforts of Dutch-American football coach Thomas Rongen (played by Michael Fassbender in Waititi’s film) to turn around the amateurish American Samoa team. And, while a decade is yet to pass since the documentary’s release, Waititi sees no problem in retelling the story again so soon — because the Pacific Islanders have an oral storytelling culture.

“There’s no written word for us,” the filmmaker explains. “So it’s all about telling stories, and retelling stories again and again — and embellishing them more and more until they become mythology. So, for me to tell this story and make everything exactly spot on and accurate, and to show every single thing that actually happened, that would be boring. You’d watch the documentary if you wanted that. If I was going to do it, I was going to ‘Taika-fy’ it, and change some stuff. The heart of the story is all true — I just added more jokes!”

For anyone who has seen a Taika Waititi film — from his celebrated sophomore picture, Boy, to campy vampire mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows — you’ll know the score. The ‘Taikification’ process consists of the following: a slight heightening of reality, a handful of larger-than-life characterizations, the odd twisted truth, much touchy-feeliness, and several choice homages. That crane kick from The Karate Kid shows up in Next Goal Wins, as do knowing nods to both Rambo and The Matrix. But the clearest influences come from sports films.

“Definitely Cool Runnings,” Waititi nods, “but I also looked at other sports films to get some ideas. Another good one is Miracle, which is Kurt Russell in the true story of an ice hockey team. And the best thing about that one is the montages — the training montages are really well done. And I’ve got like 20 training montages in this film, or that’s what it feels like!”

“If I’m writing a particular scene, I’ll play a particular song over and over, and think about how I’m going to shoot it — the timing of things. It’s a really nice way for me to feel like the film’s already finished, and I can see it.”

Taika Waititi

Set to the ever-welcome, clickety-clacking rhythm of Dolly Parton’s 9 to 5, the most memorable of Waititi’s montages benefits from the filmmaker’s soft spot for a needle drop. In previous films, whether he’s cueing up Vivaldi, anachronistically deploying David Bowie in Nazi-era Germany, or cranking up Led Zeppelin and Guns N’ Roses to spur on Thor, Waititi’s musical choices speak to an admirably open mind — one that refuses to allow snobbery or ill-favour to get in the way of a good time. But he’s a musical man, having sung backing on Ora’s latest album, scooping a Grammy for producing the Jojo Rabbit soundtrack, and religiously listening to music whilst penning his scripts.

“If I’m writing a particular scene,” Waititi says, “I’ll play a particular song over and over, and think about how I’m going to shoot it — the timing of things. It’s a really nice way for me to feel like the film’s already finished, and I can see it. This’ll happen. Then that’ll happen. Then boom, the chorus!”

“I used to find writing so enjoyable,” he adds, “because it was this thing I got to do. I got to escape, and no one was paying me to do it. It was a passion thing. But, over the years, it became a job and, honestly, now it’s one of the less exciting parts of my day. It’s become harder, and lonelier.”

“It’s a film about hope and something we all need to be reminded of, which is: slow the fuck down, be happy, and the happier we will be around each other.”

Taika Waititi

Could it be pressure? Jojo Rabbit not only won Waititi the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, but also saw him receive a BAFTA, and a Writers Guild of America Award. Do these accolades loom large every time he puts pen to paper?

“There is pressure,” says Waititi, “but I’m fine with it. What actually happens when you win an Oscar for writing is that every single thing you write — from text messages to email — are written by an Oscar-winning writer. That text, where I’ve just written ‘What’re you up to?’ That’s an Oscar-winning sentence!”

And all of those Oscar-winning sentences have put Waititi in serious demand. Among his upcoming projects — take a deep breath — there’s a film adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s dystopian Klara and the Sun, a television adaptation of Charles Yu’s National Book Award-winning Interior Chinatown, a Star Wars movie, a television remake of 1981 fantasy adventure Time Bandits, and a likely third season of Our Flag Means Death, the HBO pirate comedy in which Waititi plays Blackbeard. To prepare himself for this substantial slate, the filmmaker has started rewatching his past projects in a bid to reappraise and develop his style. He’s even scrutinizing Next Goal Wins in this way, which was filmed pre-pandemic, in 2019.

“I think distance and time are really good ways of coming to terms with things,” Waititi reasons, “and help you accept that you made decisions that felt good, proper, and authentic to the story in the moment. And, like them or not, you’ve got to stick with them. Because, unless you’re a psychopath, you can’t just go and re-edit your film every year because you’ve decided that something needs to change.”

It would also throw off the delicate balance of Waititi’s films — particularly Next Goal Wins. For there are weightier, more profound considerations hidden in the humour of the filmmaker’s latest, from issues of parental grief to transphobia. This, you’ll find, is the thread that weaves Waititi’s work together: coaxing audiences in with froth and fun, then sneakily starting important conversations. His films aren’t sugar-coated, as such, but rather operate as Trojan Horses, smuggling otherwise sidestepped subjects into the spotlight.

“For instance,” Waititi explains, “with Boy, that’s essentially a comedy about child abuse. Hunt for the Wilderpeople is about the foster system in New Zealand, which has been a problem for us New Zealanders, how we’ve treated our kids. So I’ve always been interested in those sorts of things, to be able to bring an audience in, to welcome them with humour and lightness, and then deliver some sort of message.”

And there it is: the elusive “takete” and “kiki” of Taika Waititi. Eight films in, and the New Zealander has quietly broached more hard-hitting topics and taboos than many of even our most stonyfaced filmmakers. He’s tackled arson and anti-Semitism, touched on suicide and bullying. But that’s the skill of his storytelling — he knows such subjects can’t be ignored, but is committed to showing us the world doesn’t turn on doom and gloom alone.

“I think we all just need to step back and ask: what are we doing? Why don’t we just chill out — and play the game?”

Taika Waititi

“I feel like, as a filmmaker, you need to be saying something,” Waititi says. “So, even if people look at Next Goal Wins and say: ‘Oh, it’s just soccer with some jokes here and there,’ that’s just one glimpse of it. It’s a film about hope and something we all need to be reminded of, which is: slow the fuck down, be happy, and the happier we will be around each other.”

“Football is a religion for people,” he adds. “It’s more important than life. That’s true. People live and die over a game of football. And it’s a game! But life is a game. So I think we all just need to step back and ask: what are we doing? Why don’t we just chill out — and play the game?”

Photography: Christopher Sherman

Fashion Direction: Sahar Nooraei and Haley Dach

Grooming: Melissa DeZarate (A-Frame Agency)

Photo Assistant: Shane D’Acosta

Feature Image:

Shot on location at Absolutely Fabrics Studio.