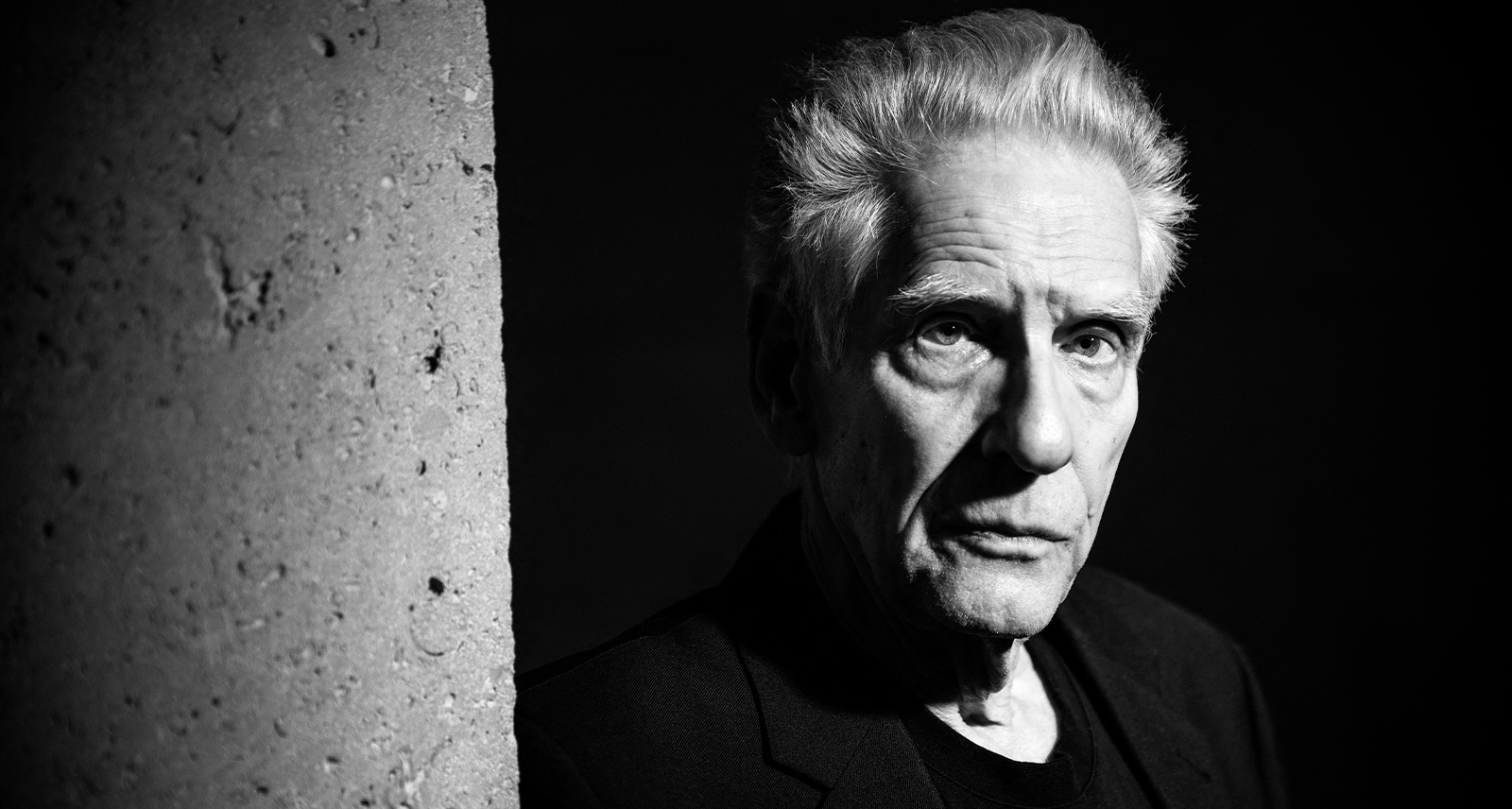

Director David Cronenberg Talks Technology, Body Horror & “The Shrouds”

Film auteur David Cronenberg is often hailed as the original creator of body horror — although he says he never came up with the term. To him, the body is an obvious subject matter. His films often revel in an interplay of sci-fi and technology blended with the human body. His contributions to genre storytelling are seen in his classics such as Scanners, Shivers, The Fly, Dead Ringers, Videodrome, Crimes of the Future, and in his most recent entry, The Shrouds, which played at TIFF and releases in theatres this April.

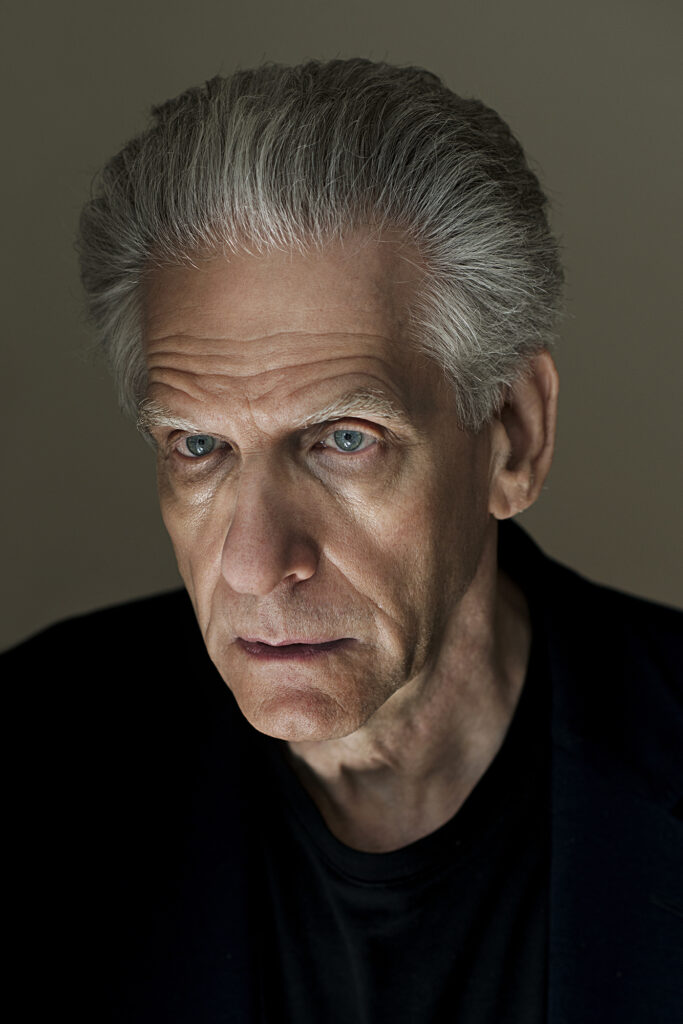

For someone who explores the dark side of humanity and technology, Cronenberg is surprisingly calm and soft-spoken, with a wicked sense of humour that’s often disarming. It is these very qualities that Vincent Cassel tried to channel as he played Cronenberg’s doppelgänger in the film. While the world sees the obvious similarities, Cronenberg laughs, insisting that he just doesn’t see it — except for the hair, of course.

“One of the primary drivers of art is dealing with things that disturb you and bother you and confuse you.”

David Cronenberg

The Shrouds is a personal film for the Toronto-born filmmaker as he drew inspiration from the death of his wife, Carolyn, in 2017 — although he argues that all his films are personal. Steeped in grief, the film follows Cassel as he builds a device to watch his wife’s body decompose in real time.

Here, the self-professed nerd discusses his contributions to cinema, and his latest film.

You’ve said that to examine the human condition automatically meant examining technology. What is your relationship with technology and why is it something so prevalent in your films?

It just seems natural to me and of course, it’s even more obvious now because of iPhones, the internet, and digital technology. Film is a technological medium. There’s always major technology involved whether it was in the old days of films or now, and you only have to walk onto a film set to see that. It’s not something that I dwell on, though I feel free to invent technology. I guess that’s the sci-fi part of myself. You can invent technology like I did in Videodrome. You can imagine technology that doesn’t exist yet, but you can feel that it’s something that probably will. And for a nerd like me, that’s kind of exciting to bring to life.

Is it safe to say that the future of technology excites you rather than scares you?

Well, it’s interesting because a lot of art is dealing with things that scare you, even if it’s just death, or whatever it is that bothers or disturbs you. You can have the illusion of having some control over it through your art and you can manipulate it and play with it and imagine it and do things with it. I think that one of the primary drivers of art is dealing with things that disturb you and bother you and confuse you.

So then, what scares you?

Well, I think it’s obvious and certainly in The Shrouds: it’s dealing with the death of someone close to you. What do you do with that in your life? How do you survive it? How do you continue on?

It’s also a discussion in the film of what happens when — in this case, it’s a love affair — ends with a death, and then if there’s another potential love affair, how do those two things go together? Is there some residue of the original love affair?

In one of the first scenes in the movie, a potential date for the widower, who is Vincent Cassel, says, “Well, this is very intimidating” because he’s talking about his dead wife and that could be an issue for people. It doesn’t have to be a death either. Could be somebody who’s been married a long time, and the marriage is broken up, and somebody finds a new lover. These are things that have to be dealt with, and of course, it’s not always sci-fi and it’s not always technology. I throw that in the movie because it’s me, but it’s the stuff of normal melodrama.

“In film, what is the main thing that you feel? It’s the human body.”

David Cronenberg

Vincent Cassel looks so much like you. Was that intentional to have your personal story be portrayed by someone who’s your doppelgänger?

That was sort of strange because I did consider other actors. I mean, when I write the script, I deliberately don’t like to think about an actor because I want the character on the page to develop as it wants to, and if you start to think about a particular actor, and if you start to shape it for that actor, that can restrict the life, the growth of the character. And then if you don’t get that actor for whatever reason — doesn’t want to do it, isn’t available, or it’s too expensive — then what happens? So, I deliberately don’t do that. And honestly, it seems odd, but I don’t think that I look at all like Vincent but the hair. Some, however, did feel that he was playing me because he had known my wife, Carolyn, so he had some personal connection that way. He did think that he was definitely playing me. He was more chilled than he normally is. He’s normally quite quick, he’s twitchy and nervous. He thinks that I’m very calm and very chill compared to him. I guess that’s true. So, he would play that, and that was lovely. I swear it was unexpected. I wasn’t looking to cast someone who maybe sort of looks like me. Literally, I mean, if you look at that face, that is not me [laughs].

Body horror and transformation of the body is your specialty. You’re exceptional at it. Why is that something that inspires you as an artist?

In film, what is the main thing that you feel? It’s the human body. I mean, the face of the body is part of your body. So, I think filmmakers are obsessed with bodies and our actors because that’s their instrument; I think [in] film more than poetry, which can be very abstract. Film is pretty much grounded in the human body to me, so it’s an obvious subject. And then when you talk about life and death, when you talk about growth, it’s all about the body. Body is reality because our understanding of reality comes from the way our eyes and ears work. So, to me, it’s not an obsession, it’s just an obvious subject. It’s the subject.

Featured image by Julien de Rosa/AFP via Getty Images.