Warp Speed Ahead: How Canada Is Leading the Technological Charge to Make the Hyperloop a Reality

On the afternoon of February 6, 2018, millions gathered around smartphones and laptops to stream billionaire futurist Elon Musk as he fired his cherry-red Tesla roadster into orbit aboard his SpaceX rocket ship, the Falcon Heavy. He landed two of the three reusable rockets back on earth, in balletic tandem, eight minutes later. The iconic South African–Canadian CEO once again made history by pushing us into the future, much like his hero Nikola Tesla, the cultish inventor he named his electric-car company after.

This has been Musk’s M.O. since he cashed out of PayPal to spend his dotcom fortune turning science fiction into fact. But one of Musk’s greatest legacies may be a technology he didn’t come up with and isn’t even currently building – the Hyperloop.

It’s based on the idea of sending people or cargo in levitating pods through a near-vacuum steel tube at the speed of sound, or about 1,200 km/h. This would get you from Toronto to Montreal in 39 minutes, or less time than it takes to watch an episode of Black Mirror.

Father of spaceflight Robert Goddard first came up with the idea for a vacuum-tube train back in 1909. His concept eliminates rail friction with levitation and reduces air resistance with a depressurized tube, recreating the physics of flying at 200,000 feet. The vactrain was largely forgotten until 2013, when Musk dubbed it the Hyperloop in a 57-page, open-source white paper that compared the scientific principle to an air-hockey table (though most professional designs have ditched his “air-bearing” idea for passive magnets), and argued that it’d be faster, cheaper, and more sustainable than current modes of transportation.

Then he challenged the tech world to build it because, well, he was kinda busy. It worked. Thanks to Musk’s cult of personality and carnival-barker marketing instincts, his now-copyrighted rebrand of an old-timey technology — albeit one that looks like how we imagined we’d be travelling in the future — created a new industry from thin air, pulled in fellow billionaire entrepreneur Richard Branson, and set engineering students around the world ablaze with excitement. And much of this Hyperloop push is coming from Canada. Thanks to the feds putting billions into the Innovation Superclusters Initiative and National Trade Corridors Fund, our perfectly spaced cities and lack of high-speed rail, and the leading-edge engineers of the Toronto–Waterloo tech hub, we’ve become leaders at all levels of this new technology — which may be arriving faster than we think.

•••

Deep Dhillon had never even heard of the Hyperloop when he first arrived at the University of Waterloo to study math and computer science. Then again, his dad built him his first computer in grade 8, and it didn’t have Internet. “I had a bit of data on my phone,” he recalls, “but I didn’t know what to do with it.” Everything changed two years later when he moved to Brampton, Ontario, from a small agricultural town in the Tarn Taran district of Punjab, India. “I look back and think how far I have come,” Dhillon grins. “It was like a dream going to SpaceX.”

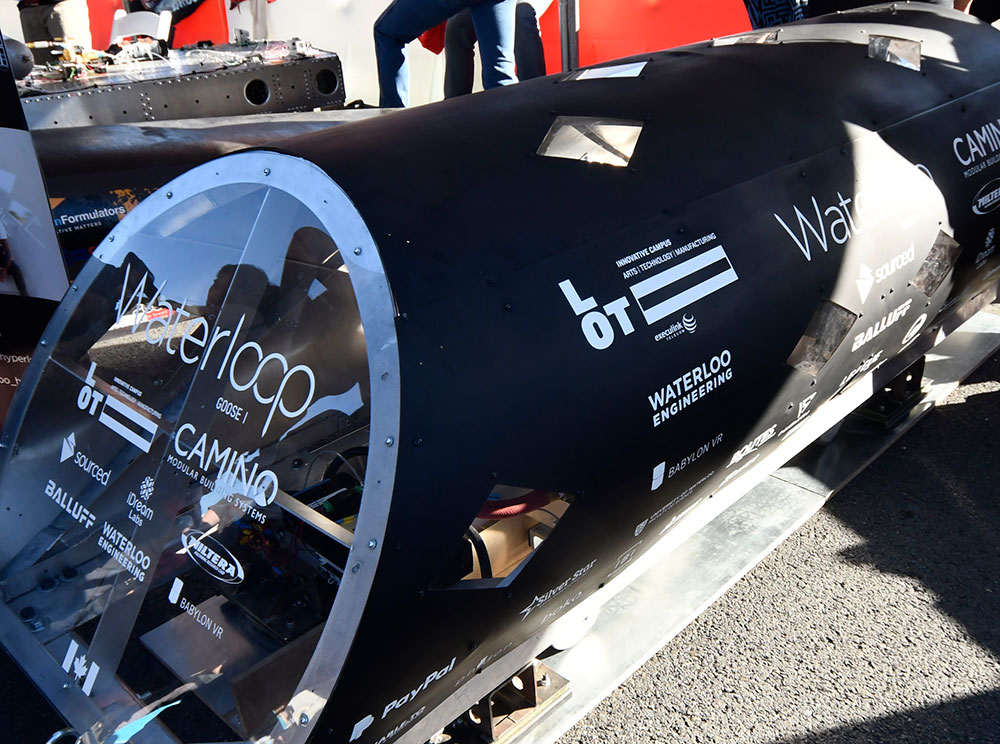

One way that Musk, who Dhillon describes as “like Iron Man, or like Lex Luthor but the nicer version,” has stayed involved is by building a mile-long test track on the SpaceX campus in Hawthorne, California to host the student engineering Hyperloop Pod Competition. Dhillon was recently promoted to technical director for his university’s wonderfully named Waterloop team. Comprising over 100 students, this extracurricular club has been developing a pod that they’ve named Goose, after the birds that plague their school grounds.

Their canoe-shaped black fibreglass prototype is 2.5 metres long and 150 kg, and lifts the pod on a thin air cushion while spinning magnetic wheels propel it forward. SpaceX received 1,700 applications after announcing their competition; by January 2017, that was whittled down to 27 teams, including Waterloop, which had just successfully tested the world’s first pneumatic Hyperloop levitation system.

They were the only all-Canadian team, and among the top 15 at August’s Weekend Competition II after a week of pre-run evaluation. They also brought the only completely contactless pod that never touched the rails, which at this stage of development made their design slower but more innovative. They received vital feedback from SpaceX engineers and testing in a vacuum for the first time but didn’t complete the 100-point safety-test checklist needed to enter the final race. “They treat it like a rocket,” Dhillon says. Only the top three teams made the final cut. Germany’s reigning champ WARR Hyperloop hit a top speed of 323 km/h, or almost four times faster than its winning January run, while Switzerland’s Swissloop placed third, and Paradigm (a Can-Am collab between Newfoundland’s Memorial University and Boston’s Northeastern) came in second at 101 km/h. Paradigm was the only team to do away with magnetic levitation in favour of an air-bearing system, making them world pioneers of that technology, “primarily because it was the original idea that Elon introduced,” team member Ben Lippolis told CBC after their win.

Team Waterloop, meanwhile, is hard at work on Goose III, and awaiting design approval from SpaceX to enter the third competition this summer. Though all these prototypes are at very early stages and made by students with limited experience and funding, what their designs offer over more established operations is an experimental approach to the technology that pushes boundaries — because they don’t know what those boundaries are yet.

“Whatever they show in the movies can be done — it’s just that we don’t know how yet,” Dhillon says before proudly displaying the latest iteration in their engineering building workspace. “If you asked people in the past how doors open automatically, they’d be like, ‘Oh, that’s magic!’

“Now we’re living in a world where such things are possible.”

•••

“Transportation is partly about moving people from A to B, but it’s also much more than that,” says Matti Siemiatycki, a University of Toronto associate professor whose focus is infrastructure planning, financing, and project delivery. “There’s a symbolic dimension to transportation which is really about our own imagination and what’s possible. We dream about these types of ideas,” he says, offering examples like Star Wars’ lightspeed, Star Trek transporters, and The Jetsons’ pneumatic tubes. “The way we think of these big initiatives is how this technology will change our relationship with time and space.”

Transportation advances do shrink our world. When my grandfather sailed from Paris to Montreal as a toddler in the early 1900s, his steamship took five days, a fraction of the months Samuel de Champlain spent using sails. Modern airplanes cut that trip down to five hours.

“Whatever they show in the movies can be done — it’s just that we don’t know how yet.”

Canadian history is, in many ways, the history of transportation innovation — from Indigenous peoples travelling via canoe and dogsled and Europeans arriving by boat, to the steam-powered transcontinental trains tying our sprawling, sparsely populated confederation together, and the cars that spread our cities outward. Now Hyperloop promises to connect our populations by making travel between major metropolises quicker than crossing their downtowns during rush hour.

The Toronto–Ottawa–Montreal corridor was the only Canadian route among 10 winning entries in a “Global Challenge” competition held by Virgin Hyperloop One last fall, which saw over 100 pitches to host the first-ever Hyperloop. (“Virgin” was added to the name late last year when Richard Branson was named chairman in the wake of co-founder Shervin Pishevar’s leave of absence due to sexual misconduct allegations.)

Inspired by Musk’s callout, Hyperloop One now has over 300 employees, and a prototype pod that hit 400 km/h with only 300 metres of acceleration in their Nevada test loop. They have ambitious plans to put operational systems in service by 2021.

“We are the big game in town,” says Dan Katz, Hyperloop One’s director of global public policy and North American projects, over the phone from his L.A. office. “All these things we are thinking about, we’re accomplishing.” At the least, they’re gathering momentum internationally and sparking excitement in Toronto and Montreal.

“Those are two major cities at a nice distance for us to install one of the first systems – it’s not too close, not too far,” explains Katz. “Canada has this real opportunity as the only G7 country that doesn’t have high-speed rail in some form. It’s in a position to leapfrog over everyone else and jump straight to Hyperloop.”

Hyperloop One is now waiting on a grant application from Transport Canada to fund a feasibility study. As is Canadian competitor TransPod Inc. — co-founded in 2015 by Sebastien Gendron, a France-born aerospace engineer who’s worked for Airbus and Bombardier. TransPod has an even more ambitious vision to build a Hyperloop connecting Quebec City, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Detroit, and Chicago. Their initial cost analysis claims their proprietary Hyperloop — still in the design stage with a prototype due this fall — would cost 50 per cent less and travel four times faster than high-speed rail.

“We’ve had some feedback from the government that Toronto–Montreal is a complicated corridor because we’re dealing with two provinces, and Via Rail is pushing for a dedicated line. They asked us to also look at the corridor between Calgary and Edmonton,” Gendron adds from his small office in the tech hub of downtown Toronto’s MaRS Discovery District. “Those are two big cities that should be connected, and the ridership makes it economically viable.” TransPod is seeking government support to build a 10 km test track near Calgary, and has already secured land for a smaller half-scale track three hours outside Paris.

Gendron predicts cargo will get the green light before people do, and that e-commerce and courier companies like Amazon and FedEx are likely to be among the biggest customers. “As it’s a new transportation mode, we’re trying to be pragmatic and acknowledge that regulatory agencies will approve the system for freight first. Even if we’re compliant with regulation and the system is bulletproof, they’ll want to see that running for one or two years with goods before approving it for passengers.”

Taking advantage of Gendron’s European roots and the state of American politics, the Toronto-based Hyperloop company also has offices and partnerships in Italy and France. “Thank you, Trump,” he laughs. “It’s definitely helping us. The trade agreement in progress between Canada and Europe is a good fit for us. There’s no appetite to support U.S. companies as we speak, and as there are only a few players, we’re in a good spot to take the lead.”

Gendron believes that the lack of political will that has been hampering infrastructure development in recent decades is finally giving way. He predicts a commercial Hyperloop line will be running by 2030. “Autonomous cars. Electric cars. Musk landing rockets. We’re starting to see a wave of people with ambition, and we’re also facing challenges, like climate change, which are pushing people and society to innovate,” he says. “There is a shift happening in the Canadian mindset. I used to hear that Canadians were risk-averse, but with Monsieur Trudeau we are seeing a change, and a lot of initiatives promoting innovation in general. Now it’s time to see if Canada will walk the talk.”

•••

“We have a tech-forward community, and we have a lot of transportation problems, so it doesn’t surprise me at all that we have a lot of people dreaming of how to make things better,” Siemiatycki says. He notes Canada’s skilled engineers, great entrepreneurs, plugged-in public who hears about and supports these ideas, and good track record with public–private partnerships. But, he adds, “What’s important to keep in mind is Hyperloop is not the first moonshot. And for all the ones that have hit, there’s a scrapyard of ideas that didn’t.”

The monorail, for instance, will whisk you around Disney’s Magic Kingdom, but its Tomorrowland promise has been otherwise reduced to a memorable fourth-season Simpsons parody. New York’s subway was initially proposed as a pneumatic-tube train. The Bennie Railplane failed to bring propeller-driven trains to Scotland in the ’30s. Germany’s Wuppertal Suspension Railway, an elevated train hanging below a track built in 1901, still runs today but never expanded beyond 20 stations. The “revolutionary” Segway only moves tourists about. And the “hydrogen highway” linking Vancouver and Whistler failed after fuel-cell cars never caught on, and the five fuel- ling stations were shuttered.

Whether or not these technical ideas work may not matter, if they don’t work better than what we already have, or if something even more effective and efficient comes along. That’s not to mention concerns about environmental impact, affordability, gentrification and, of course, where to put hundreds of kilometres of Hyperloop.

“That’s the challenge railways have had,” Siemiatycki says. “Via Rail can’t get a new right-of-way between Toronto and Montreal. It goes through a lot of different landscapes, and it’s expensive and technically challenging to buy those up. So there’s the planning concerns and political dimension of how one does that.”

Hyperloop One has suggested building along government-owned highway corridors or abandoned rail lines. Another solution is burying it, which is where Musk re-enters the picture. In late 2016, he founded The Boring Company to make tunnelling 10 times more affordable both for standard traffic and to house the Hyperloop for long-distance routes. Musk even tweeted he had “verbal government approval” for a tunnel connecting New York and D.C., though that was disputed by surprised bureaucrats, and others have doubted his ability to reduce the cost of tunnelling enough to make an underground Hyperloop feasible.

Siemiatycki also warns that “these technologies can distract us from day-to-day priorities,” taking focus and funding away from less sexy solutions that improve our lives incrementally. But while realistic about potential challenges, he’s also optimistic about potential benefits.

“Throughout history, the idea of building physical connections that bring people together has been overwhelmingly positive. It’s how societies grow and thrive — building bridges is both literal and metaphorical.”