How the Tyson-Jones Jr. Fight Represents the Allure and Inadequacy of Nostalgia

Mike Tyson and Roy Jones Jr., two of the world’s greatest boxers circa 1990, are set to fight in an exhibition match this Saturday in the Year of Our Lord 2020. They are on a card that features: Nate Robinson, one of the NBA’s most spectacular dunk artists 10 years ago, who’s fighting a guy who’s famous solely because YouTube exists; Badou Jack, an aging former titleholder, who’s fighting a journeyman with no business being in the ring with him; and, at the bottom of the marquee, Viddal Riley, a boxer best known for training the previous opponent of the aforementioned YouTuber, who is fighting a mixed martial artist.

Boxing fans like to get red-assed about clown shows like this. Which is not unfair. The sport’s reputation wasn’t great in Tyson’s and Jones’s heydays*, and it hasn’t really improved. Yet there are fighters today who have the talent and charisma to be stars on the same order of magnitude as Tyson or Jones. Deontay Wilder and Tyson Fury are close already, but others come to mind, too, like Anthony Joshua, the soft-spoken Brit with a torso carved from stone or Oleksandr Usyk, the clown prince of his division and a tactical menace. And those are just the heavyweights.

The makings of a new golden age of boxing are there, yet there remains a bigger audience for an exhibition between the shadows of two legends, a basketball player, and this idiot. Why is that?

Part of it is that the business of boxing has disillusioned its fans. With so many sanctioning bodies at the top tier of the sport, there are now about fourteen thousand belts. That structure often rewards champions and up-and-comers for avoiding each other, as they try to preserve their records and maximize paydays (Floyd Mayweather was a pioneer of sorts in this regard). Tyson and Jones were among the last of a certain breed of champions who couldn’t be contained by that**.

But there’s also a morbid curiosity, the same kind that once drove us to spend our hard-earned nickels to see sword swallowers and bearded women. If you’re reading this, I assume you’re someone who has talked at length about impossible sports matchups, a subgenre of arguments that get unreasonably heated after a few beers. Would the ’96 Bulls have beaten the ’02 Lakers? Would Ali have beaten Joe Louis? Rocky Marciano? Mike Tyson? This match will give us more empty calories for those arguments which will continue as inexorably as the march of time.

There’s another reason, though. Similar to the one that made the Mayweather-McGregor fight happen, there’s an obliterating force now at the centre of arts and entertainment: Nostalgia is a balm, and even in less difficult times, we will pay well to evoke it.

New things aren’t as profitable as faded, old, familiar things, especially when they’re glossed up in big and superficial ways. Disney is making shot-for-shot CGI remakes of all their classic movies, remakes whose value is judged almost exclusively by their fidelity to the original cartoons, which cost 75 percent less to make. Marvel continues to pump out multi-million dollar extensions of its universe (or as people who are not Martin Scorsese call them, “films”) each of which includes half a dozen superheroes. Any fewer and our overactive synapses stop firing. We get bored.

Boxing is a prime candidate for such a cultural facelift because it’s steeped in nostalgia. The characters are huge personalities we all know, and, because it’s real life and not a comic book, most of the greats couldn’t face one another “in their prime.” But now they can—sort of.

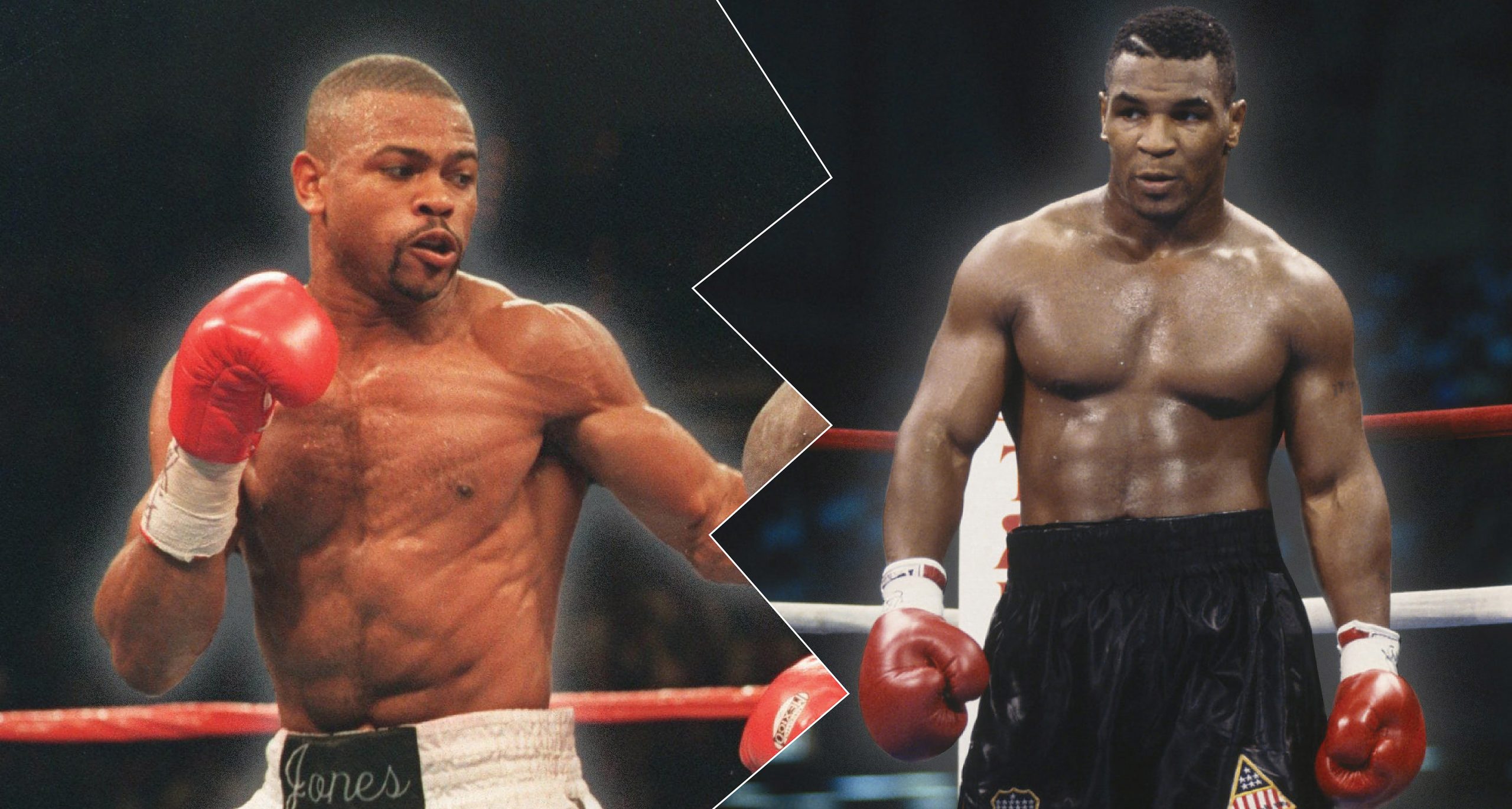

Mike Tyson was one of the most ferocious heavyweights in history and arguably one of most compelling athletes of the century. He was a one-man tragedy—a villain, a hero, and a victim wrapped in an explosive young man’s body. Roy Jones Jr. had some of the most vicious hands of any puncher to walk the earth. He also had an abusive father for a trainer who left him with physical and psychological scars. He continued to fight professionally until 2018 when he was 49, ancient by boxing’s standards.

Most who stand to make money on this fight don’t care about tacking a new ending onto these stories. It’s not really their job to worry. After all, the fighters themselves don’t seem to mind. So, we’ll watch them go at it for eight rounds, about 30 years less formidable than they once were. I hope they’re paid well.