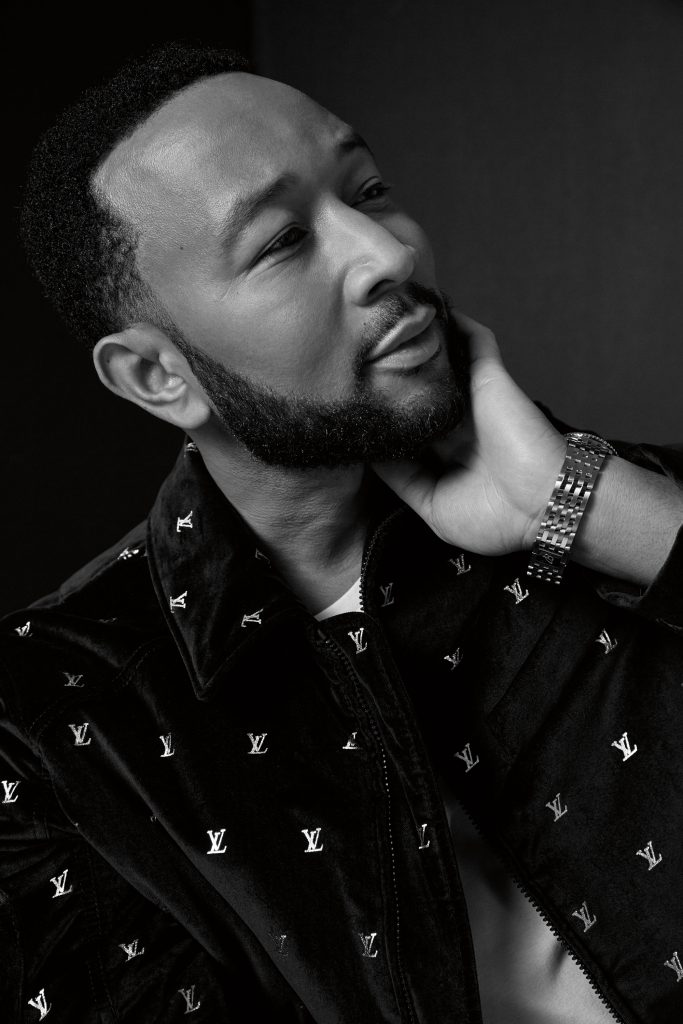

John Legend’s EGOT Was Only the Beginning

John Legend doesn’t mind that you know him for his ballads. Speaking over Zoom a few days after his performance at the 74th Primetime Emmy Awards — where his new song “Pieces” offered an appropriately mournful accompaniment to the in-memoriam segment — the 43-year-old singer-songwriter is characteristically good-humoured about the suggestion that he’s a musician people look to when the moment calls for gravitas. Legend takes the implication that he’s the industry’s go-to funeral accompanist in stride. “I think part of it is just my roots,” he reflects, treating his continued success as a balladeer and tone-setter for sombre occasions, in spite of cheekier hits like “Number One,” as an honour. “I grew up singing gospel music. I would sing at a lot of funerals and other events where people needed inspiration. And so these types of events are part of my musical heritage.”

Heritage is important to Legend, who burst onto the scene in his twenties as one of the most coveted rising talents in R&B, and who became the second-youngest winner of the coveted EGOT before he turned 40. It’s something to stay true to wherever his career and his politics take him, a thread he comes back to whether we’re talking about his music or his activism, both of which he sees as rooted in his upbringing in Springfield, Ohio. Shortly after the release of Legend, his first double album — which he cheerfully notes was narrowed down from 80 to 24 songs — Legend is as happy to muse about the career retrospective Las Vegas residency he closed this past October as he is eager to promote his new album.

RIGHT: SUIT BY BALMAIN; SHIRT BY DRIES VAN NOTEN.

As an artist in his prime, Legend has a quality of the statesman, with an air of seriousness about his public image. Legend is at ease with the possibility that his ballads have won the day in the public’s perception of him, even though his albums have always contained more irreverent tracks like “Used to Love U” or the new album’s sensual “Honey.” He seems secure in the knowledge that the nature of streaming and his residency keep his back catalogue, in all its contradictions and variety, alive. A fresh-faced old soul, Legend is the picture of mid-career contentment: aware of his plum position in the industry, energized by the chance to revisit his songbook, and secure in the knowledge that he has plenty of tracks left to record.

People ask me that about my political views, too. Do I feel like I need to be more careful? I feel like it’s liberating to tell my truth.

Though the playful eponymous name drop of his eighth album suggests an artist intent on legacy-building, Legend doesn’t seem all that concerned about how the new work might go over beyond the things he can control, like sequencing. He slickly breaks down Legend’s 24 tracks into two acts like a maitre d’ previewing a menu, offering tasting notes as he describes the first side’s upbeat “Saturday night” jams versus the second side’s more relaxed and intimate “Sunday morning” vibes. He’s unbothered by my suggestion that with the album’s length, he’s placing himself in the pantheon of artists such as Ella Fitzgerald, Bob Dylan, and OutKast, pointing out that the double album as a form is more fluid in the age of streaming, where fans make their own playlists and listen at their own pace. Once the prized young collaborator of artists such as Lauryn Hill, Mary J. Blige, and Alicia Keys, the now-seasoned Legend sounds most excited about the prospects of hosting the work of other musicians himself, citing the tracks with Muni Long, Saweetie, and Rick Ross as some of the album’s highlights.

Although Legend is energized by bouncing ideas off other artists — “I never felt like I left it,” he says about collaboration during the socially distanced phase of the pandemic — the material on Legend often feels personal. On “Pieces” he thinks of grief as a teacher, evoking his and partner Chrissy Teigen’s public mourning following the loss of their stillborn child. Then there’s “Wonder Woman,” a devotional hymn, with a video that prominently features Teigen. Does it cost him more to be personal at this stage in his career, given how much people think they know about his and Teigen’s lives? “I think it’s easier, honestly,” he counters. “People ask me that about my political views, too. Do I feel like I need to be more careful? I feel like it’s liberating to tell my truth.”

In recent months, telling his truth saw Legend direct his attention on social media to the recent midterm elections. Though plenty of political artists focus their philanthropy and activism on the bigger picture of the Senate or the House, Legend went smaller, doing his part to spotlight local district attorney races, which he sees as the best pathway to create a restorative society.

“A lot of what I want to do is educate people,” he says, occasionally slipping into second-person plural as he explains the purpose behind his tweets, like a politician speaking earnestly of his grassroots campaign. “A lot of people didn’t know who their district attorney was, didn’t spend a lot of time and energy focused on what they did and how their policies affected everyone’s lives in their communities. Part of what we’ve done is raise awareness that district attorneys matter, and that ending mass incarceration is a goal we should look toward. Once we educate people about that and they start paying attention to who their district attorneys are, then they can make their own decisions about what policies and what direction they think their community should go in.”

The expectation that artists of his stature should “shut up and sing,” as critics once said of The Chicks, is not unfamiliar to Legend, who’s been in his fair share of Twitter skirmishes. But the calculus is different, he thinks, for someone with a direct investment in and lived experience of the causes he amplifies online. “I think a lot of it comes from being a Black man in America,” he says, gesturing to a broader tradition of Black activism in the arts. “I think we feel the stakes more than a lot of other communities feel them. We have been victims of bad policy in the United States for so long that we care a lot about politics. We care a lot about fighting for justice in the political realm. We’ve seen the effects that racist policy has had on our communities for centuries. I think we feel a special sense of responsibility and a special sense of urgency when it comes to how these political issues affect our lives and our families’ lives.”

Legend emphasizes that mass incarceration is not an academic problem for him as a Black man in America, even one with his degree of wealth, fame, and security. He sees his championing of marginalized communities as the fulfilment of his own personal legacy. “I wrote an essay when I was 15 that said I wanted to become a successful musician and use my platform to help my community,” he says. “I’m going to continue to do that. It’s rooted in who I am, rooted in where I come from, and rooted in my knowledge that these things are not just academic: they affect real people’s lives. And I don’t feel removed from those communities who are dealing with these issues, despite the fact that I’ve achieved some success and some fame and some fortune.”

Hearing him speak this softly of his accomplishments, it’s easy to forget that Legend is American industry royalty, having scored the coveted quartet of an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony — the first winner to do so in four consecutive years. With the exception of the Grammys, he confesses a bit sheepishly, he pulled off this achievement mostly by accident, only realizing the significance of the hardware he was accruing as he barrelled toward his Emmy for producing Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert in 2018. The exclusivity of the club, a sort of Mensa group for multi-disciplinary artists, is not lost on him: “Jennifer Hudson was 17,” he notes, when I point out just how few winners there are. Nor is he unaware of the significance of being only the second Black artist to make the list after Whoopi Goldberg. Mostly, though, he sees it as freeing him up from the psychic energy of pining for awards. “Now that I’ve gotten this kind of status,” he says, “I truly don’t need to win anything else. I’m fine. I truly just want to make music that’s impactful.”

Though he’s good on the awards front, Legend isn’t through with the work that got him there. Since April, he’s been revisiting his career in his “Love In Las Vegas” residency at the Zappos Theater at Planet Hollywood, synthesizing his musical past and present. The purity of a residency appeals to Legend, who says that keeping the show in one place means putting the money into the production, the stuff audiences see, rather than in transportation costs. It’s also an opportunity for him to get meta, thinking about what makes a John Legend show. “It gives me the chance to explore my entire catalogue and my roots and talk about the journey that’s brought me to where I am.” Describing the show’s four-part structure, his curatorial instincts kick back in as he patiently walks me through its trajectory from his gospel days in Ohio, to his formative time in Philadelphia and New York, to an impressionistic piano bar section, and finally to a baroque scene rooted in the feathers, glitz, and glamour of Vegas. The subtext of that journey is that Legend remembers where he comes from — and is comfortable with where he is now.

The idea of the Las Vegas residency has shifted in recent years from an institution where aging musicians lay down the last tracks of their careers to a place where mid-career stars such as Legend can explore their roots with plenty of distance left to run. Vegas itself has modernized, Legend points out: its investment in emerging chefs and hoteliers has transformed it from a glorified retirement home into something much more dynamic. Legend is proud to represent a more diverse vanguard gracing Vegas and bringing new audiences along with them, joining the ranks of Cardi B and Drake, younger artists who have brought hip hop to a strip that has been more associated with rock and power pop.

“I think now people are doing it more in the peak of their careers,” he says. “You still have to have enough repertoire to justify getting a residency. But artists like myself and Silk Sonic and Usher, we’re still in our primes as artists, and we are celebrating the journey we’ve been on to this point, while we’ve still got a lot of new music left in us as well. I’m happy to be part of that group of artists who are, I think, modernizing Vegas, diversifying Vegas.”

As for how he feels about being at the self-described peak of his career, Legend remains even keeled. Although he routinely revisits his musical origins in his residency, he is unsentimental about the past, seeing it as continuous with the present. “I think what the streaming era has done is really flatten time,” he says with some awe, “made all times connected to each other, so that anything that came out in 2004 is just as accessible as anything that’s come out now. It makes it so everything’s connected and everything’s accessible and everything’s available. Because of that, there’s more exploration and availability of people’s catalogues now.”

Some artists might balk at that sense of availability, concerned by how easy it is for listeners to drift across different phases of an artist’s musical history, much as they’d quibble with being associated with ballads when their body of work encompasses so much more. For Legend, though, the fact that the Internet has allowed people to instantly connect with his music — all of it — is part of what makes having a repertoire and still being around to revisit, contextualize, and develop it so exciting.

“There are just so many ways for people to feel connected to the past and to have access to this music that was made decades ago all right there at your fingertips. They don’t have to go to some obscure record store to find it. It’s all there.”

Photography: Gioncarlo Valentine

Styling: Matteo Pieri (The Wall Group)

Grooming: Ron Stephens II

Makeup: Pamela Farmer

Production: Caroline Santee Hughes @ Hyperion.LA

Photo Assistant: Wacunza Clark