Moya Garrison-Msingwana Sees Humanity as Art

For Moya Garrison-Msingwana, fashion is less about adornment than transformation. In his exhibition “A Thread is a Vein,” he explores the link between anatomy and apparel. “I love how fashion amplifies or changes the architecture of the human body,” the artist explains. “The shapes and structures are fascinating to me; it’s an art form that’s become so ingrained in humanity.”

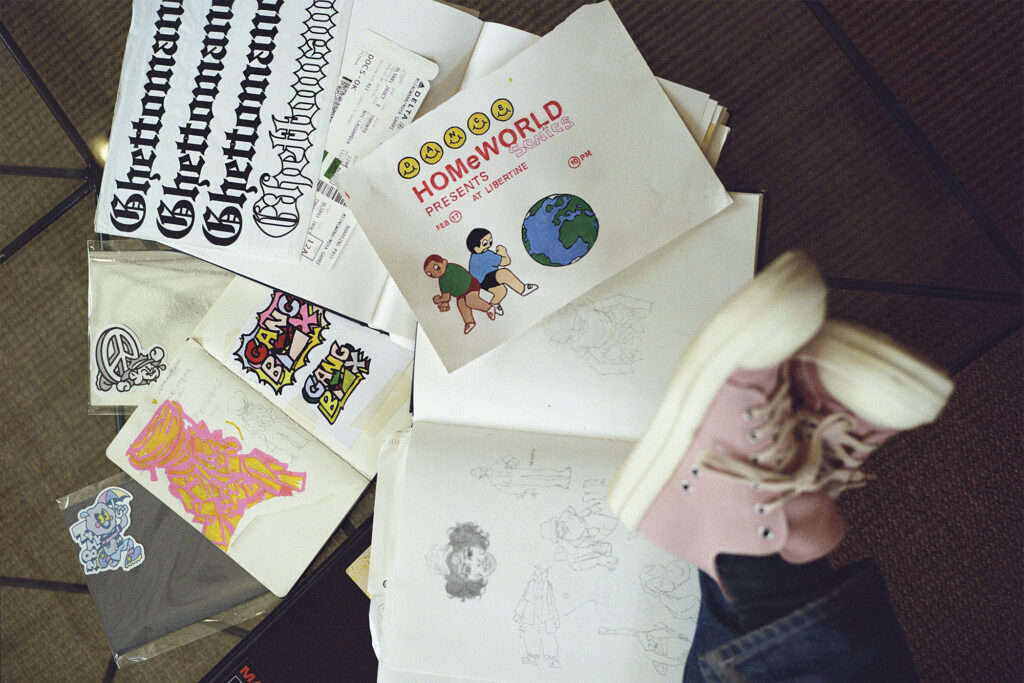

Also known by the artist handle GANGBOX, Garrison-Msingwana works across a variety of mediums — including painting, sculpture, and digital rendering — to conjure his own uniquely absurd vision of the world rooted in fashion, pop culture, and the supernatural. He has collaborated with clients including Loewe, Adidas, and Stüssy, and recently launched his first U.S. solo exhibition of paintings, “LAUNDRY 002 – A Thread is a Vein,” in New York and Los Angeles.

The collection of 12 paintings is a continuation of his remarkable LAUNDRY series, which is predicated upon the idea of piles of clothing possessing their own life and sentience. In Garrison-Msingwana’s “uncanny universe,” clothing is near biological. “Who knows what the internal structure of these piles actually looks like,” he explains, “beyond just the regular human form.”

The Book for Men caught up with Garrison-Msingwana to discuss his upcoming multimedia projects, how anime continues to inspire his work, and why he thinks AI could never truly replace artists.

You grew up watching and drawing Japanese anime, which often features characters with an almost supernatural stylishness. How important was fashion to you and your art from an early age?

I didn’t really associate the two for a long time, but I was really interested in character design. Especially in anime because they have these really bizarre characteristics — like Kenpachi, in Bleach, has bells at the tips of all the spikes on his hair. Things like that were just so beyond, bending physics and reality, and I always really admired that. Japanese storytelling, and honestly most cultures’ storytelling, stories from my dad’s culture — he’s Tanzanian from Dar es Salaam — are so reality-bending and folkloric and magical, and I realised that I could blend it all together easily in my work.

“It’s really beautiful to encounter people that have their own completely different interpretations of my work. Honestly, that keeps me going.”

Moya Garrison-Msingwana

With “LAUNDRY 002” there’s a wonderful absurdity to how unwieldy the piles are. How inspired were you to create fashion that is similarly physics-bending?

That does totally tie in. I just don’t really worry about the rules. I think it’s important to keep that dreamlike nature to it; a kind of floatiness that can exist, or a rigidity with some of the clothes and the fabrics that would be so technically hard to achieve. I’d need a whole other career just to be able to make a lot of that stuff, or to even understand where to begin with real textiles and real fabric. So painting it just liberates me to experiment, and then maybe I can collaborate and leave the other areas of expertise of making it real to somebody else.

You recently exhibited this collection in L.A., and New York before that. What was it like going coast-to-coast with your work?

Spectacular. I’ve never felt more accomplished and proud. And so much of that is due to Hannah Traore, my gallerist, and her belief in me and support in getting people interested in what I’m doing. It’s really beautiful to encounter people that have their own completely different interpretations of my work. Honestly, that keeps me going in many ways. I have a lot of theories about what I’m doing, but mostly I’m just doing what comes natural to me.

“The nerdy kid in me is like, ‘Wow, this is really happening, I’m going to be able to contribute to this world of incredible art that I’ve always admired.’ That kid is like my best friend.”

Moya Garrison-Msingwana

What are some of the insights you gained?

Somebody brought up homelessness to me and how these figures reminded them of bag ladies, or bag men, who live with everything they have. And that makes me think even deeper about what aspects of yourself are intrinsically you. One of my good friends told me that he looked at the piles and felt a sadness. He thought that it looked like these piles were very burdened. Even though you can’t see any physical traits, I guess it was making him think about how heavy it would be to carry all those things, and how limiting it would be. Things like that can set me off in new directions and are beautiful ideas that wouldn’t necessarily have come from my own mind.

You’ve spoken before about wanting to do more multimedia and textile work. What are you working on now?

I can’t say too much right now, but essentially I’m working with a company who are providing materials for me to figure out how to design sculptures. They are essentially PILES, but for a brand. So they’re maybe not as chaotic as I would make ones for my own purposes, but it’s my first endeavour in trying to make them real using textiles. I’m profoundly excited about working with textiles in limited runs in a sustainable way.

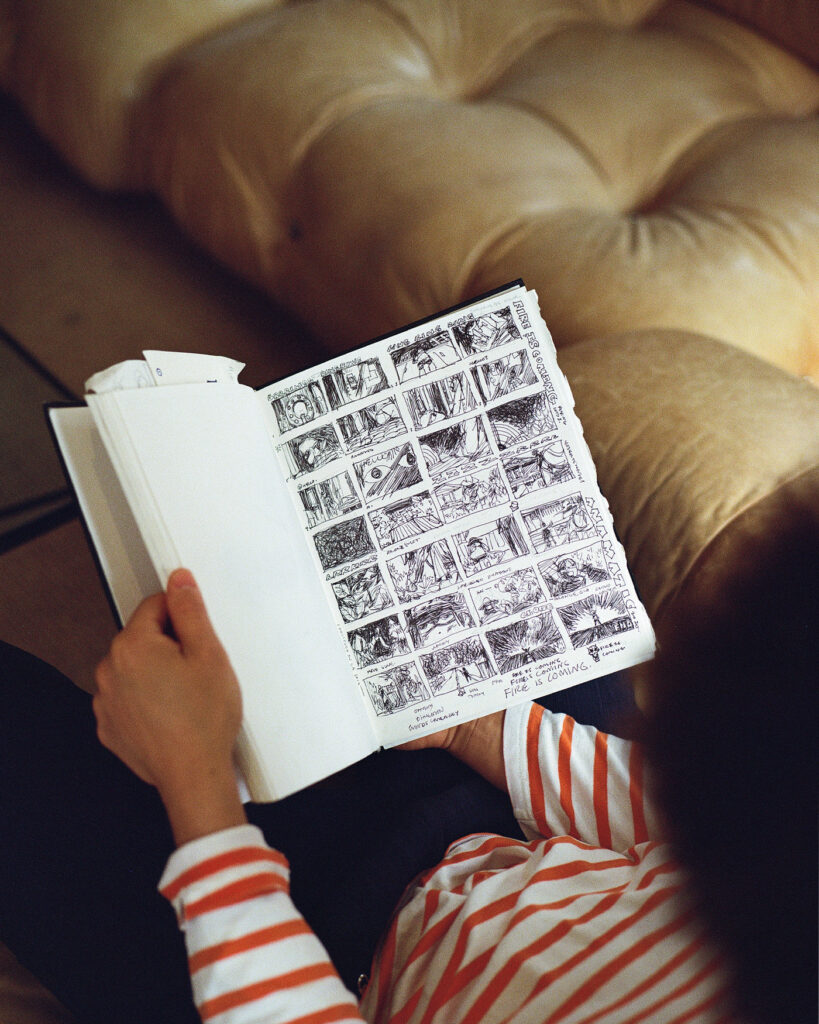

I’m also moving to the UK at the end of the year because I want to work on a comic book full time, and I’ve decided that that’s the place that’s best to do that (laughs). I think I’m going to treat it like [Katsuhiro] Otomo, where I’ll probably put like 10 years into it because I’m going to be a bit of a psychotic perfectionist about it all.

The story is called Ghettomancer, but I’m just world-building right now, coming up with characters, their motivations, and overarching stories and themes that I can take from my real life and experiences and kind of codify them or stick them into this very supernatural world that I’m working on. The nerdy kid in me is like, ‘Wow, this is really happening, I’m going to be able to contribute to this world of incredible art that I’ve always admired.’ That kid is like my best friend.

“I love to leave evidence of humanity in everything I do. I leave the tape on my paper works, and you can see fingerprints and mistakes that I painted over. It doesn’t take away from the beauty, in fact I think it adds to it.”

Moya Garrison-Msingwana

As a working artist, how do you feel about the rise in AI-generated images? Does it inspire you to make your work more bespoke to human experience?

Definitely. The idea of AI having consciousness or trying to supplement humanity is what concerns me. I like technology, but when it comes to my work, I’m definitely an analog guy. The solitude and the simple act of exploring and using my hands and my mind to solve problems is my favourite part. And I love to leave evidence of humanity in everything I do. I leave the tape on my paper works, and you can see fingerprints and mistakes that I painted over. It doesn’t take away from the beauty, in fact I think it adds to it in many ways.

I don’t think that AI could ever get in the way of that, or compete with real artists, to be honest. And I feel like the people who want that out of art don’t appreciate artists and art very much. It’s probably mostly advertisers who don’t want to pay a model, and who would prefer to generate an image for five cents. I just don’t see the point of trying to fake that, or trying to force some evolution to that thing that is already so essential and beautiful about being human, you know?

Photography: Scott Pilgrim, shot on location at East Room.