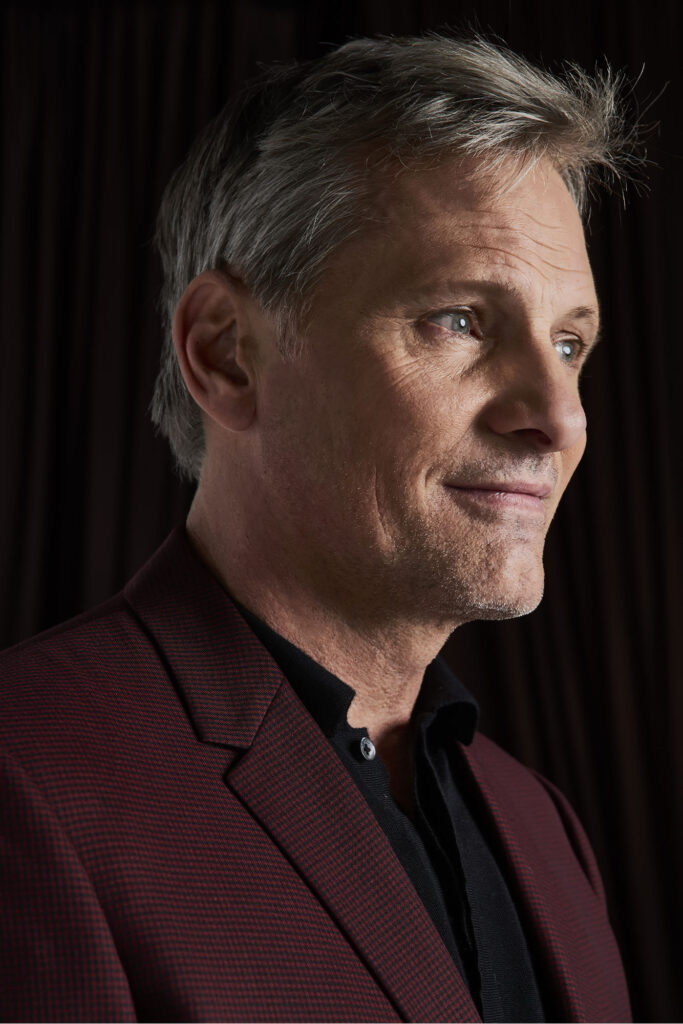

Viggo Mortensen On His New Film, ‘The Dead Don’t Hurt,’ & Modern Westerns

Viggo Mortensen is riding back to Hollywood on horseback.

Cast as Aragon in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Mortensen enjoyed the sort of big break that most entertainers dream of: three annual releases provided a steady stream of work and widespread exposure. Yet successful film series — whether it’s Lord of the Rings, The Hunger Games, Mad Max, or even James Bond — often stick their actors with a peculiar problem: if you do the job well, you’ll spend a decade or two trying to crawl out of its shadow.

Daniel Craig famously said “I’d rather break this glass and slash my wrists” than play in another James Bond movie. In 2020, Daniel Radcliffe proudly told us: “I will never be in anything as massive as Harry Potter again. At a certain point, that becomes a hugely liberating realization: I’ve been freed from that definition of success.”

There’s no need to ask how Viggo Mortensen feels, however. As the director, composer, and co-star of The Dead Don’t Hurt, he can’t be confined to a single character (or job title, for that matter). The subversive Western feature proves he’s a modern Renaissance man.

Talk to Viggo Mortensen, and you’ll understand the difference between ‘cinephile’ and ‘movie buff.’ His enthusiasm colours each frame of The Dead Don’t Hurt, a 129-minute Western steeped in scorching desert sun. These rugged backdrops pay tribute to genre staples; it even shares a production setting — Durango, Mexico — with The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly.

As much as the film resembles its predecessors, however, The Dead Don’t Hurt is more than a conventional Western shot with modern cameras. “It is a very particular sort of Western,” Mortensen says. “It clearly breaks with the conventional archetypes.” For his characters — French Canadian and Danish immigrants — rural Nevada is uncharted waters. And, off-screen, it seems like The Dead Don’t Hurt represents something similar for Mortensen. Though it’s only his second time in the director’s chair, the Western drama establishes Mortensen as a force to be reckoned with.

“In the late 19th century, neither novelists nor journalists were interested in ordinary women’s stories.”

Viggo Mortensen

Mortensen remembers writing the script during a strict, mid-2020 lockdown — a far cry from the film’s sun-drenched vistas. “I happened to be in Spain at the time, and for a few months, you couldn’t go more than 250 meters from your house — you just weren’t allowed to. There were police everywhere, patrolling all that,” he says. “I felt limited in my movement.”

Fittingly, movement — whether it’s on horseback or by foot — is a near-constant presence in the film, carrying conflict from shadowy saloons to sun-bleached homesteads. “In retrospect, maybe that had something to do with it,” Mortensen says of his cabin fever.

Still, as the actor describes his creative process, it seems that surroundings were a small factor. Instead, he talks about a specific, ‘lightning-strike’ inspiration. “The first image was certainly of the little girl [that] you see in the film, in a forest of maples, red oaks, black walnuts, hickories,” says Mortensen. “It’s almost identical to the place where my mother used to play as a kid, right on the border near where Lake Ontario goes into the Saint Lawrence River.”

Mortensen returns to this image multiple times as he talks: tall trees, faint moonlight, mossy trails. This idea became a starting point for the rest of Mortensen’s story. To fill in the gaps, he asked himself questions; where did she live? How would she act? Who does she become?

“The little girl that you see has a very strong sense of herself. She’s kind of stubborn, maybe a little mischievous and intelligent, very independent; a real free spirit,” says Mortensen. “That was inspired by the personality of my mother. Vivienne — the character that Vicky Krieps plays, the lead role in our movie — she’s very much that way. She has her own mind.”

It’s interesting; The Dead Don’t Hurt has plenty of side plots, but, hearing Mortensen talk about Vivienne, it’s obvious that he built the story with her character at the centre. As soon as she steps into the frame, Vicky Krieps commands the audience. When I ask about this, Mortensen is eager to answer.

“In the late 19th century, neither novelists nor journalists were interested in ordinary women’s stories,” he says. “They wanted to tell the stories of men and their wars: cattle barons against sheep barons, building the railroad, the discovery of new places, the push westward — outlaws, sheriffs, all that stuff. They just weren’t that interested in telling stories of women.”

Of course, film fanatics will find an exception or two: Joan Crawford’s Johnny Guitar filled cinemas in 1954, while Kim Darby became a star in 1969’s True Grit. “There have been movies — sort of ‘exploitation-type’ movies — where a woman behaves like the violent man in the Westerns and grabs a weapon, shoots a bunch of bad guys, and you get some immediate gratification as an audience member,” he concedes.

Still, he’s quick to explain that The Dead Don’t Hurt takes a different approach. “But that’s not the kind of story we wanted to tell. [Vivienne] is limited, as everyone is, by the time she lives in, by the fact that she’s a woman. She’s not some avenging angel; she’s an ordinary woman. She just happens to be really tough, psychologically. She’s probably the toughest person in the story.”

“It was important to show the diversity — ethnically and linguistically — of society back then. […] They spoke different languages, had different cultures, different customs.”

Viggo Mortensen

Vicky Krieps agrees that The Dead Don’t Hurt has pushed the limits of the Western genre. When she draws real-world parallels, however, she’s a bit more explicit. “Vivienne carries a message from a time that’s long gone,” she says. “She lives in a world where people are fighting over land and are killing each other […] regardless of who else is there. Today, we are supposed to have moved on and to be evolved, but nothing has changed, really. The same people are oppressed and the same people are the oppressors.”

Mortensen thinks on these words for a moment. He agrees with Krieps, but adds that, “My point of departure — writing a story or making a movie or editing — is not ideological.” To Mortensen, any real-life parallels are a reflection of the film’s honestly. “Movies where the characters are well defined, the actors are good, and the storytelling works — where there are real human beings, on screen with real problems, conflicts, obstacles, and relationships — you naturally tend to compare [the movie] to your own family, your own town, your own society, the times you live in. It just happens naturally. You don’t have to set out to do that to get people to think about it.”

Instead of an ideological standpoint, Mortensen says the film came from a natural sense of curiosity. Vivienne, he explains, wasn’t meant to be “exceptional” in the traditional sense; she wears plain clothing to the local pub, where she bartends for extra cash. She raises a young boy and teaches French to the neighbourhood children. Yet the plot never dulls; moments of intensity — trauma, isolation, ailments — boil just beneath the surface. To Mortensen, that’s realism.

“[Vivienne] is an ordinary woman who happens to have a very strong sense of herself,” he says. “I think many women were that way — they had to be back then. Women were the ones who kept homes going, raising kids, keeping society going while men were off doing their things.”

The Dead Don’t Hurt captures this concept on film. The setting, as Mortensen describes it, is “basically lawless, dominated by a few corrupt, powerful men who [use] violence to achieve their goals.” That’s a classic setting for a Western film, but with Vivienne at the centre, we see a new perspective. Instead of settlers battling the elements with brute force — as another, more conventional 1800s American West period piece might show — we see Vivienne grappling with a society that isn’t built for her. Writing the script, Mortensen wondered: “What have the consequences for her — physically, emotionally, economically? What has she had to do to get by?”

Krieps answers these questions on screen. She channels Vivienne’s emotions, both heavy and light, with an authentic, palpable rawness. Her performance emerges in contrast to the grandiose surroundings, giving the story a refreshing sense of realism.

“In this chaos, Vivienne exists, and she’s lost, like everyone is lost, but something makes her strong,” Krieps says. “It’s not that she’s physically strong […] she’s strong out of the act of forgiveness.” Krieps’ interpretation — like Mortensen’s — comes from an idea about the past. “Something that women have done, I think, over centuries, is to forgive men for their pride,” she adds.

To achieve a sense of authenticity, Mortensen led the cast in an extensive research effort. “I tried to find anything I could to document the period historically, just to make sure everything looked right, sounded right,” he says. Viewers will notice adobe buildings, a reference to the area’s past as part of Mexico. Wood frames, meanwhile, convey a classic American expansion style.

Visuals were only half the battle, however. From the outset, language underscores the region’s diversity. Small as it is, the town is filled with Spanish, French, and Dutch voices. “It was important to show the diversity — ethnically and linguistically — of society back then,” he says. Indigenous people, European settlers, and immigrants colour the mid-1800s town. “They spoke different languages, had different cultures, different customs,” Mortensen adds.

To inform the costumes and conflicts, Mortensen dove into archived images and letters penned by women from the era. Other Westerns were also helpful, he says. “The old Westerns — the first ones in the silent era — [were made] fairly close to the period that that they were depicting,” explains the actor. Taking note of each detail, Mortensen studied, “The architecture, the interiors of saloons and houses, the clothing, the way people rode horses and handled wagons.”

The process paid off: from the set to the cast, the language to the score, it’s a truly immersive period piece. The Dead Don’t Hurt threads the needle, carefully treading the line between realism and drama without leaning too far into either side. Stunning cinematography turns would-be lulls into cherished moments of tranquility. With skillful restraint, Krieps swaps traditional melodrama for muted anguish.

On the first day of filming, Mortensen recalls saying: “I hope you will have a good time, but that the experience won’t punish you too much.” The tactful call to action became an unofficial tagline for the process, ending up on the call sheet. “I knew from the beginning that it would be hard,” he adds, “but I felt that we might enjoy ourselves as well, once in a while.”

The Dead Don’t Hurt is now available on Amazon Prime.