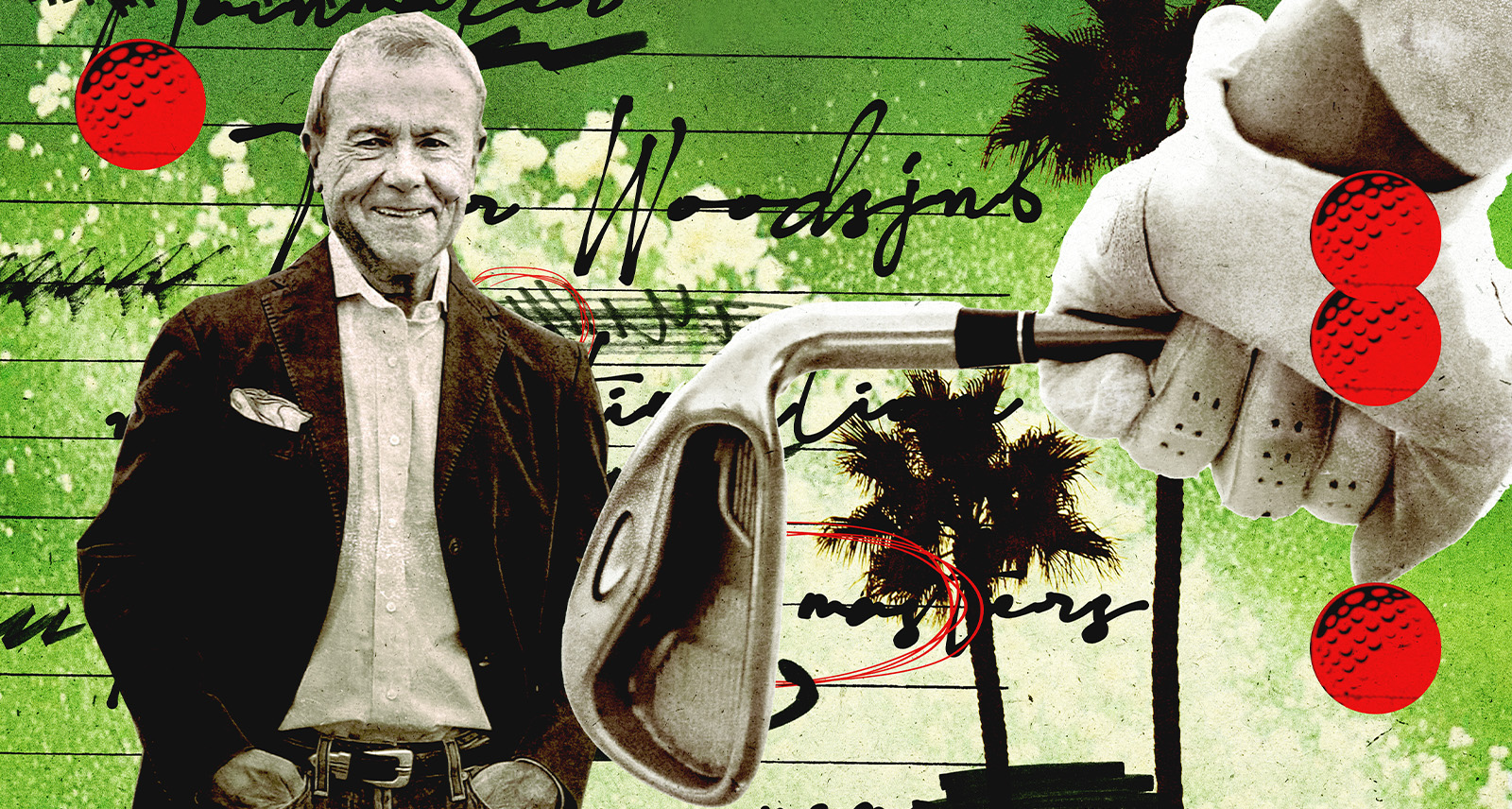

Hughes Norton, Golf’s Original Superagent, on New Memoir ‘Rainmaker’

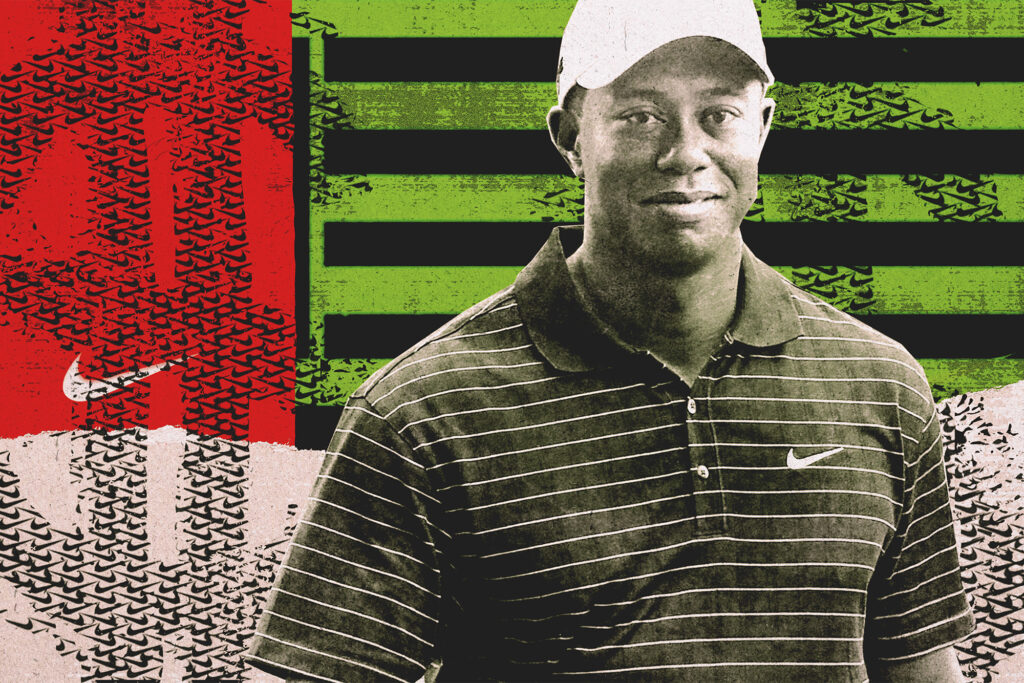

In the summer of 1998, the magazine Golf World ran a cover that featured a photo of Tiger Woods, his father Earl, and a man named Hughes Norton. The line below their faces read: “The Father, Son and Holy Ghost.” It was hyperbolic, but only slightly. Here were the hallowed figures sent from the heavens to save golf as we knew it, the cover story seemed to say. And there, on equal footing with the Woodses in that new Holy Trinity, was Hughes Norton — a mythical, magical, almost otherworldly entity in sporting circles at the time; the superagent who minted more than $120 million in endorsement deals for the most exciting golfer in history.

Just two months later, Norton was cast out of the kingdom. Not so much Holy Ghost as left for dead. After years of working at the heart of Tiger Woods’s famously tight entourage, Norton was called up by the player one morning in late September 1998. “He just said ‘I want to make a change,’ ” Norton recalls now, chatting to me from his home in Cleveland, Ohio. “He said: ‘Yep, it’s over.’”

“It was cathartic for me […] it’s not that I needed redemption so much. It’s just that there was an empty feeling with how it all ended.”

Hughes Norton

Norton was completely blindsided. “And I said, ‘Well, Tiger, let me come down to Florida. Let’s talk about this.’” Woods told him not to bother. No point. The decision had been made. “I was flabbergasted,” Norton said. “I flew down there anyway. He reluctantly came to meet me. He was a zombie — his eyes were completely dead. He looked at me. He said: ‘I told you not to come down here. It’s over with.’ And he turned and walked away. And I’ve never heard a word since.”

The years leading up to that fateful day — and the fallout afterwards — are the subject of a new book that Norton has co-written with the golf writer George Peper. It’s called Rainmaker, and the title is instructive. In his long, storied career at IMG’s burgeoning golf division, Norton made it rain like no other. He oversaw a period of explosive wealth in golf, and became one of the most powerful people in sport. In 1997, when Woods sunk his final putt on the 18th to take home the Masters at the age of just 21, the first three people he embraced were his father, his mother, and Hughes Norton. I ask him what it was like to revisit those heady days — and the dramatic downfall that followed — in the process of putting the book together.

“You don’t get to the top level of any enterprise — but especially not sports — unless you are egocentric, you are self-centred, you are selfish. You have to be, because it’s so excruciatingly difficult and time-consuming that you don’t have time for the niceties of life, or to be a normal person.”

Hughes Norton

“It was cathartic for me,” he says now. “I think that’s the best description, because there was a lot of bad stuff at the end. I’d done a job for Tiger Woods that even today people say is the most unbelievable starting foundation that an agent has ever produced for any professional athlete,” he says. “But it’s not that I needed redemption so much. It’s just that there was an empty feeling with how it all ended.”

Norton sees the book as an all-access invitation into golf’s first big bang era — a period whose mores and mindsets vibrate though the game today, not least in the current controversy surrounding LIV Golf and the injection of sovereign wealth into the sport. But it’s also, he hopes, a glimpse into the day-to-day life of high-flying agents — “the everyday blocking and tackling” — and a job defined, in the popular consciousness, by larger-than-life characters like Jerry Maguire (“Show me the money!”) or the brash, furious Ari Gold in Entourage. The reality of the role, he says, is far more subtle and nuanced than these caricatures — as much psychologist, gatekeeper, and mentor as deal-maker or money-spinner.

“The list of agent requirements is so long. You don’t get to the top level of any enterprise — but especially not sports — unless you are egocentric, you are self-centred, you are selfish. You have to be, because it’s so excruciatingly difficult and time-consuming that you don’t have time for the niceties of life, or to be a normal person.” Greg Norman, the 1980s titan of golf known for his gargantuan ego, was a case in point. “Part of my job, every once in a while, when Greg was pontificating about this or that, was to say: ‘Greg, let me tell you something. You’re completely full of shit.’”

The courage and the candour to tell the world’s biggest stars when they might be wrong — in a sea of yes-men and hangers-on — was often Norton’s greatest asset. Woods, for the most part, appreciated the directness and clarity with which Norton honed his image. It was Norton’s idea, for example, to streamline the Nike endorsement deal down to just a small tick on his chest and a tick on his cap — the now-iconic, confident minimalism that seemed so neatly to mimic Woods’s own calm and clean game; a simplicity that stood in stark contrast to some players, whose agents plastered them in logos as if they were monster truck drivers. This didn’t stop Phil Knight, the enigmatic founder of Nike, attempting to bypass Norton at “the 11th hour” and cut him out of the deal in order to save the player and the brand a few percentage points in commission. “Earl Woods, to his everlasting credit, said no,” says Norton. “But it was a blockbuster attempted betrayal.”

(Knight, he says, is “a very elusive little character. He had these odd traits. He ran a shoe company and you couldn’t go into his office without taking your shoes off. It was very bizarre.”)

“You’re human. You try to be this badass agent, but at the end of the day, you can’t help but feel empty and sort of just want an explanation. So now to revisit it all these years later, I really felt energized by it.”

Hughes Norton

This shared history made Norton’s eventual sacking, when it did come, all the more painful. I ask him whether he feels, more than a quarter of a century on, like he understands the decision any better.

“To this day, all that matters to Tiger is golf. Practising and working and competing and winning championships. And the money, quite extraordinarily, was not only secondary to that, it was an intrusion into his life. You had to go do photo sessions. You had to make commercials. You had to talk to writers. He hated all that.” Norton kept the player’s endorsement hours manageably low, but even so, Woods seemed to find that part of the job a huge irritant. “And so, in looking back, I really probably over-delivered at a time in his life when he just wasn’t ready for it. But again, I’m speculating here.”

Woods and Norton have not exchanged a single word since that day in 1998. “I had started working with this guy when he was 12 years old,” he says. “And thinking about it now, I had set Tiger up financially for life. But he would never tell me what happened. And interestingly enough, everyone that he’s broken off with — whether it’s his caddies, whether it’s his swing coaches — it’s just a case of: when you’re done, you’re done. And you’re out of his life, and he never explains why, and he’s just gone.”

“You’re human,” Norton says. “You try to be this badass agent, but at the end of the day, you can’t help but feel empty and sort of just want an explanation. So now to revisit it all these years later, I really felt energized by it. It was extraordinary. It was almost like a part of me coming alive again after all these years.”

Feature illustration by Claudine Derksen.