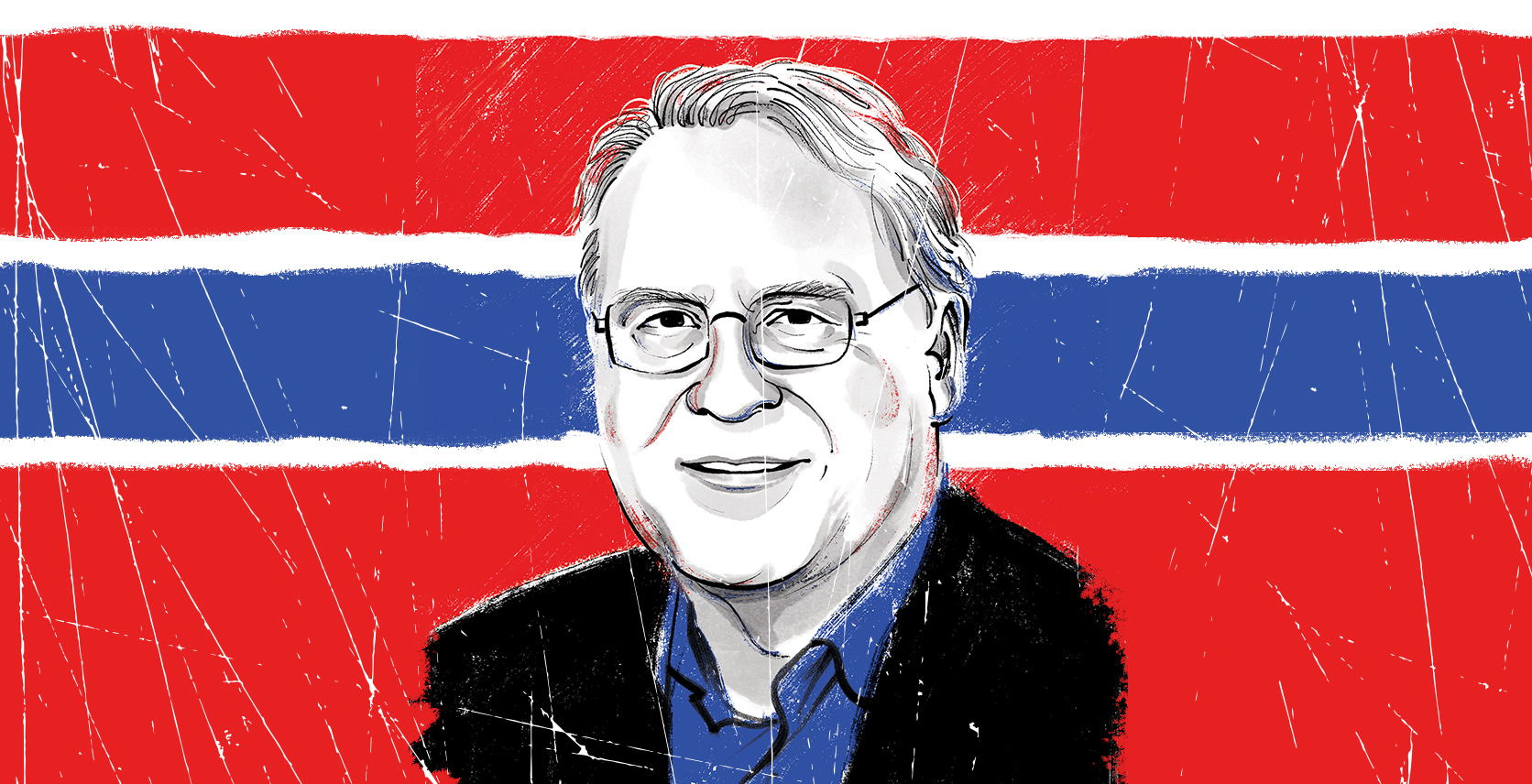

Ken Dryden Wants the NHL to Fix Its Darkest Problem Right Now

Pretty much no one’s spent more time thinking about hockey than Ken Dryden. As goalie for the Montreal Canadiens in the ’70s, he ruled the NHL, winning the Stanley Cup six times. Shortly after retiring, he penned The Game — an intimate look at Canada’s favourite pastime from behind the mask, widely acknowledged as hockey’s Ulysses, and one of the best sports books ever written. Since then, his CV’s been impressively varied — lawyer, businessman, Toronto Maple Leafs president, Liberal MP, cabinet minister — but one thing has remained constant: his obsession with the game.

Lately, however, that fixation has turned into frustration. In recent years, Dryden’s taken the issue of concussions in hockey head-on, writing op-eds and calling on sports executives to catch up with the science showing a relationship between head trauma and long-term brain damage. His new book, Game Change, focuses on the story of NHL defenceman Steve Montador, who was diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) after his death at 35 in 2015. Dryden wants to know why Montador isn’t still alive when he should be, and why the NHL isn’t doing more to prevent other players from sharing his fate. And he’s about done waiting for answers.

Back when you played hockey, were concussions on your radar?

You knew when you got knocked out. It was like in comic books, where a character is seeing stars. Later on, the phrase became “having your bell rung.” But it was just as it is now: you’re injured, and most of the time you seem fine. You get a shot to the shoulder, you’re sore, you get treatment, and a few days after you feel better and life goes on.

Now concussions are something you’re very vocal about. Why?

When you’re involved in sports for a long time, you start to see the changes. Most are exciting — the level of what players can do gets higher and higher — but there are also other developments. The last number of years, I’ve been reading more profiles, and sometimes obituaries, of former players suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s or some kind of cognitive problem. And often these are presenting at a young age. I’ve also seen the impact, in the present, of players going down with head injuries, and then a year later going down again — sometimes on a hit that seemed routine.

Is there a reason you’re focusing on Steve Montador’s life in particular?

It’s because the full story about concussions is not just about science, or about an injured player who has to retire, or about the changing nature of a game. The full story is also about the lives affected. Part of Steve’s life is playing in the NHL and going to the Stanley Cup finals with the Calgary Flames, but another part of it is head injuries. What is it like to feel symptoms an 80-year-old might feel, but at 34? What is it like to have memory problems, anxiety, and depression? In all appearances, you have another 50 years of opportunities, because you have a reputation and some money. But you’re living with a diminished self. Those are the real stakes.

“The full story about concussions is not just about science, or about an injured player who has to retire, or about the changing nature of a game. It’s also about the lives affected.”

Last year, the NFL acknowledged the connection between head trauma and degenerative diseases like CTE. Why has the NHL been so reluctant to take the same step? I mean, besides the fact that they’re facing a class-action lawsuit about it from hundreds of players…

Well, they haven’t gone before a court yet, but I think what the NHL is arguing now, in preparation, is “you haven’t proved causation.” The player may have this condition, but who’s to say it happened playing in the NHL? It might have happened when you fell down the stairs at two years old. So long as you can’t prove causation, you don’t have a case. And that was the ongoing defence for the tobacco companies and the lead companies and the asbestos companies. It’s the normal defence now in terms of climate change.

There’s a certain pattern of response for each of these questions — it goes from an unawareness of the science to a denial of the science to a playing down of the science. But I didn’t realize the next step would be to wrap yourself in the flag of science and say, “We are a modern people. We are sophisticated, evidence-based people. And so, we look to science. But science doesn’t have the answer yet.” Instead of science offering better information, it ends up being the shield standing in the way of you taking the next step.

I guess the problem is the science on CTE is still in its infancy.

Science takes time. It’s dealing with the best understanding of something at any particular moment. At one point, science wasn’t aware the earth revolved around the sun. Of course, science learns. And yet, games are played tomorrow — by professionals, but also by eight-year-olds. Parents are worried about what may happen to their son or daughter in hockey. And so, decisions have to get made according to the best information we have at this point.

So what decision should NHL commissioner Gary Bettman make right now?

The first thing is to start with the notion that a hit to the head is a bad thing. Then you say, “What steps can we take that are consistent with that?” That’s what rules are for. A hundred years ago, the rule for high sticking came from an understanding that the head is vulnerable when you play hockey. We decided to penalize high sticking and the game developed accordingly. Nowadays, if a stick comes up and you strike your opponent in the face, penalty! Automatically. At first, people said, “He didn’t really intend to!” But now the coaches don’t argue and the players don’t argue.

Same thing in terms of a hit to the head. And don’t ask me “Did he really target the head?” No. That’s not the issue. It’s not about the perpetrator; it’s about the victim. The brain doesn’t distinguish between whether a hit to the head is accidental or not. The question is about the effect it has on the brain. Start with that and the ripple effect will be significant. And players will adapt because they do all the time. Players and coaches are among the most creative people on earth because they’re always imagining their next move.

People are worried that changing the rules will change the feel of the game. Hockey fans don’t like change. Just look at what happened when they replaced Ron MacLean with Strombo!

Well, if these fans were real purists, they would know the history of this game. The game they think is unchangeable started with a few rugby players from McGill in 1875. And that game was played the same way rugby was at the time: without substitutions. Everyone played the whole game. Even more significantly, in the first 54 years of hockey, you couldn’t pass the puck forward. It had to be a lateral pass. If this game had never changed, today we’d be watching a sport moving at a snail’s pace. The fact is, this game has already changed immensely, and for the most part much for the better.

But has our love of the game changed? Between the concussion issue, the ugliness over how the NHL is handling it, and the declining number of kids enrolling in hockey, is Canada on the rocks with its national sport?

When I was a kid, it was pretty natural for boys to play hockey — in part because it’s a terrific game but also because we didn’t have anything else to do. Hockey won by default. You know, Hockey Night in Canada became a national tradition partly because there was no competition. The CBC was all there was! So in terms of the monopoly of attention towards hockey, yes, that’s changed. Now there are so many other forms of entertainment and sports to play and exciting things to do. But how many other activities in this country involve the same number of people with the same degree of obsession? Maybe there are more kids registered for soccer than there are for hockey now, but soccer has developed in Canada as a very recreational game, where you play once a week for a couple months. Hockey in this country is 11 months a year of many games and practices a week, of puck handling and skating clinics, of travelling on weekends to tournaments. It’s a full family experience. Name another activity in this country that involves so many people and so much commitment and so much endless discussion time like hockey does. I’m not sure I can.