How Does the Creative Mind Really Work? Ask Steve Brouwers

Nabokov called it the “frisson” — that subtle feeling, that electric charge that makes it possible for the artist to create. It’s impossible to teach someone how to come up with an original idea, and it’s hard to even adequately explain how you came up with an idea after you’ve had one. But nothing happens without creativity, and somehow, creative minds always end up making it work.

Steve Brouwers has been fascinated by the question of creativity for a long time. The Belgium-based author of the new book Creatives on Creativity works as a creative director in advertising, and he’s long wondered how it is that other people dream up their creations. With that mystery in mind, Brouwers set out on a mission to learn more about how creatives do what they do. Travelling across Europe, he interviewed dozens of filmmakers, illustrators, designers, and others in creative fields about their work and their creative process. The book comprises more than 40 interviews, and each of them begin with the same question: what is creativity to you?

Sharp caught up with Brouwers by Zoom in Spain — where he is currently on holiday — to discuss the genesis of Creatives on Creativity, his own creative process, and the lessons he learned along the way.

What was it about the concept of creativity that first interested you?

I work as a creative director at a television station. I’m responsible for finding ways for advertisements to be incorporated into our programs. I always work within the boundaries of a brief — I get my briefing from the advertisers and I think about, “okay, here is Mr. Coca-Cola, how can I make his summer campaign successful?” My work involves a kind of creative compromise, but the question I have — and which was the genesis of the book — is: what if nobody tells you what to do? If no one tells you what the brief is? What if you have a blank canvas, a blank sheet of paper? What do you need? What obstructs you? That was the spark.

When did you begin asking others about it?

I did a lot of talks about creativity at marketing conferences. I was meeting with all these creative minds that were there and doing their thing, so I thought: why don’t I sit down with these [people] and ask them how they work, what they need? It started there. I wasn’t really looking to write a book. It was more about gaining knowledge and learning something myself.

Outside of the conference setting, how did you choose who to talk to?

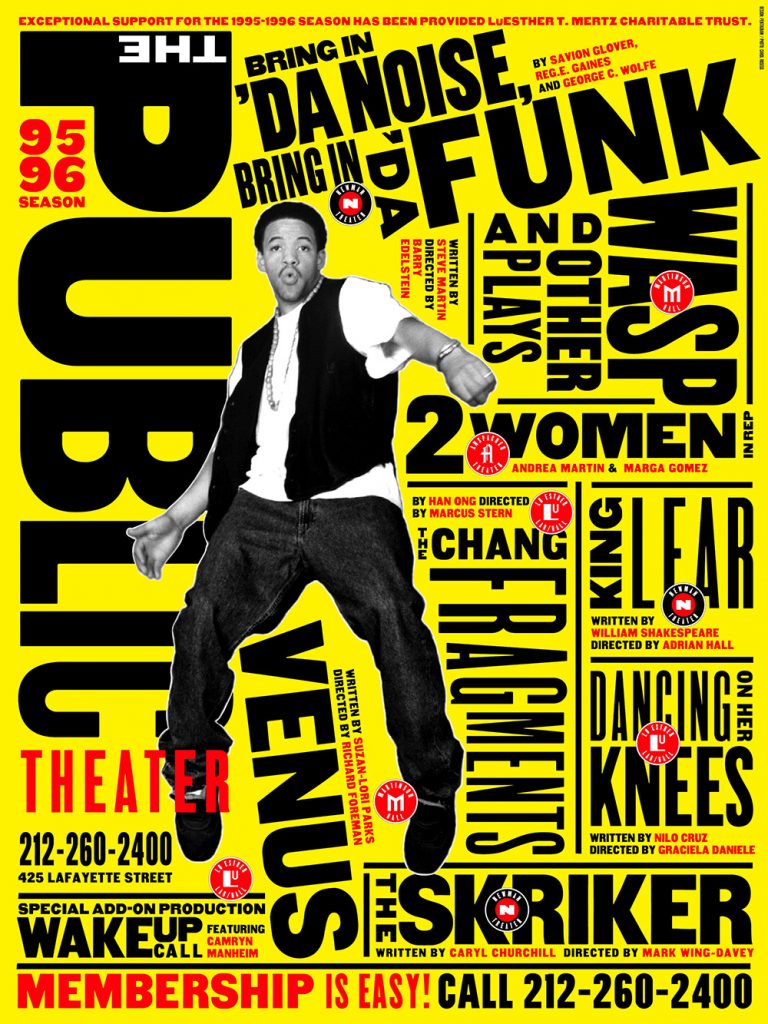

I wrote a wish list of my heroes, people I like, including George Lois, who did a lot of Esquire covers and is someone I admire. I emailed him and asked if we could speak and I was surprised that he said yes. I thought if he said yes, perhaps others would too, so I began emailing other designers and artists and travelled around to where they were to interview them. And because I work in television, I started filming the interviews, but at a certain point I thought maybe there would be some interest in making a book about this.

Why was it important for you to travel and interview these people face-to-face?

For me, it was essential to meet most of these people in person because it was my personal quest to find answers. This was pre-COVID, so I wanted to sit down and really know these people. I didn’t see all of them in person — some were by phone, some email — but for the most part it seemed really essential. It would have been easier to do it all over Zoom. It would have been a lot cheaper. But it was important for me to meet them in person.

Some of your interviewees are quite well-known and others are more obscure.

The big ones, you’ve read them everywhere, you’ve seen interviews with them everywhere. In Belgium, there are some famous artists that I didn’t ask, and a lot of people ask me why I didn’t. For commercial reasons it might have been better to do them. But I wasn’t thinking commercially, I must say. I was thinking, “who are these people who I admire and whose work I like — who talk to me, who move me? Who do I want to know in person?” There wasn’t a big marketing scheme. If people read the book, maybe they discover someone, or they get inspired by the words of a certain person and they look into their work and get to know their work.

Where did the photographs come in?

The photography is really funny because I had to take the pictures myself for the first interviews. I interviewed George Lois in his apartment and took the picture and I was so excited. I went back to Belgium and the pictures were completely out of focus and had the wrong lighting. I couldn’t use them. I thought, “okay, shit”. I have a friend who is a photographer and I told him, “look, maybe it’s best if you tag along”. I was really lucky because the pictures I took, I can tell you, they were not good.

The book is very design-oriented. It’s an art object. What was your motivation around the aesthetic of the book itself?

I wanted the book to be what I call a “visual orgasm.” That was the briefing I wanted. The words were there and were necessary, but it had to speak in images — the images had to sparkle. This was essential to me. It’s not every day you make a book.

How did you collaborate with the designer to achieve that look?

Our designer, he’s a really stubborn guy. When I met him he told me, “I don’t work for assholes. If I don’t like your head, I won’t work for you.” I asked him if he would want to design the book and whether he would be in it. He said yes, he would design it, but he didn’t want to be interviewed. Once we’d been working on the book for a few months and it was coming along, he said to me, “Steve, aren’t you missing a Belgium graphic designer in this book?” I said, do you want to be in the book? And he said, “well, now that you are asking me, sure.”

What is the most valuable lesson you learned through these interviews?

I am a person who really doubts himself. I think my ideas as I am working are not always that original, and I fear failure a lot. I think artists are really courageous people, because if they work, their work is judged in a split second. People come in, they look at the work, and in ten seconds, they have seen the work, judged it, and moved on. So you have to be really courageous.

But these designers and artists, they all suffer from the same insecurities. The insecurities are part of it. Failure is part of it. You have to have passion for the work. For me the big difference with artists is that they work without compromise. They do what they do because they have to. If they compromise, it’s not their work anymore. That’s something that really stuck with me and was really inspirational for me. You have to know where you’re going.