Olympic competition is typically used as a means of bolstering international relations. In Canada, we tend to approach such affairs with a distinctly Canadian sensibility: unassuming, modest, and deferential — even in our proudest moments. Last winter, Canadian World Champion beach volleyball player Melissa Humana-Paredes said the following to the Olympic Committee: “One mantra that I’ve been sticking to lately has been ‘this too shall pass.’ I think that is extremely relevant in both really challenging situations, but also really positive situations. What I take from that is everything will move on.”

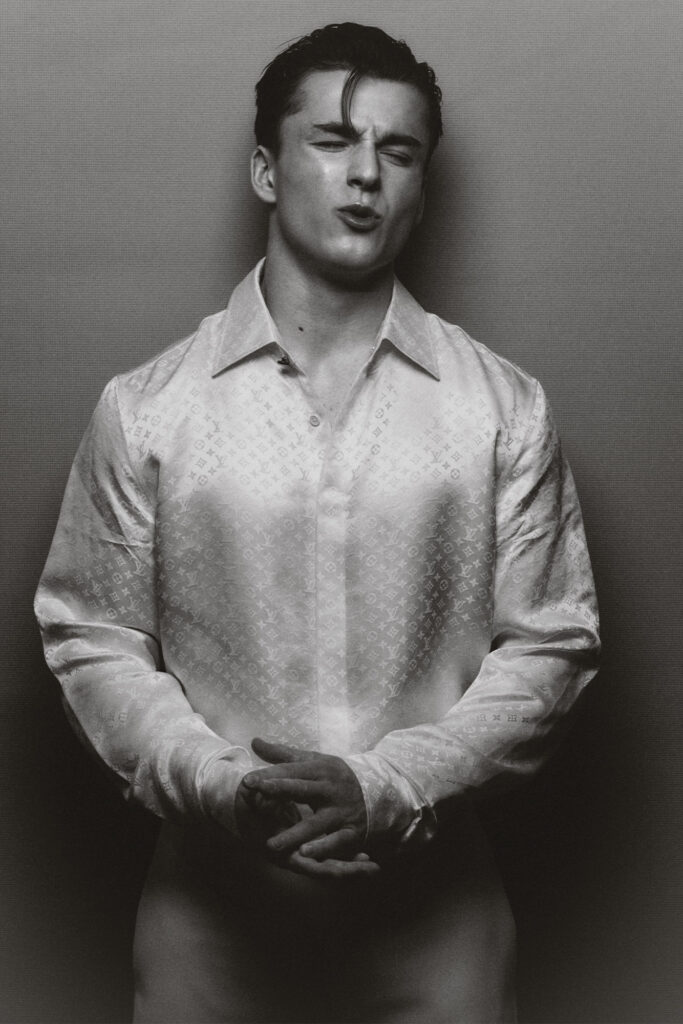

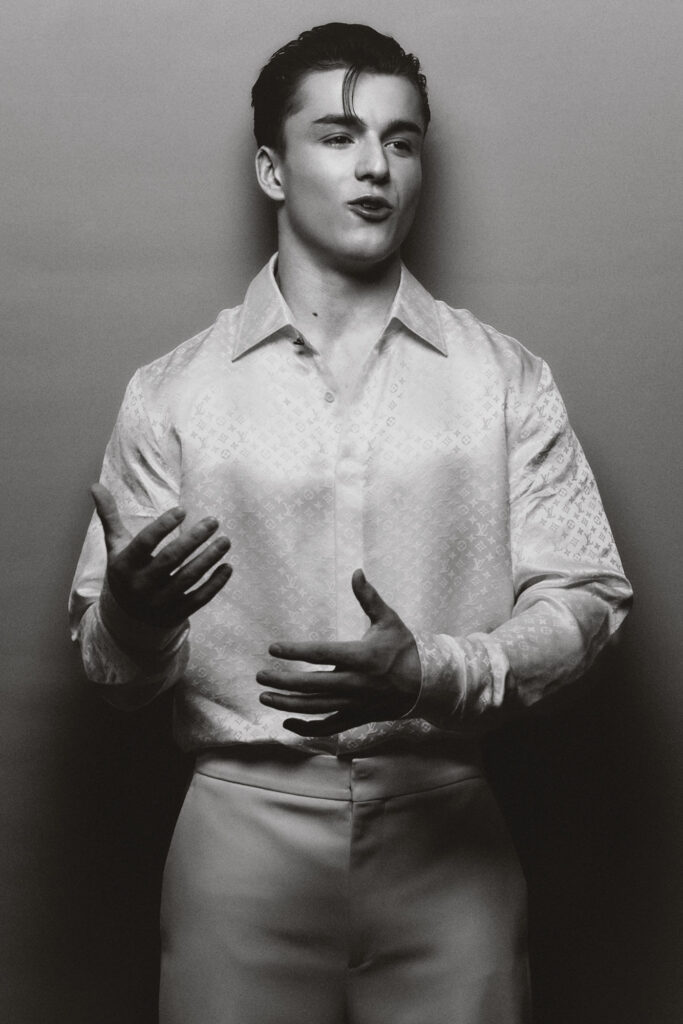

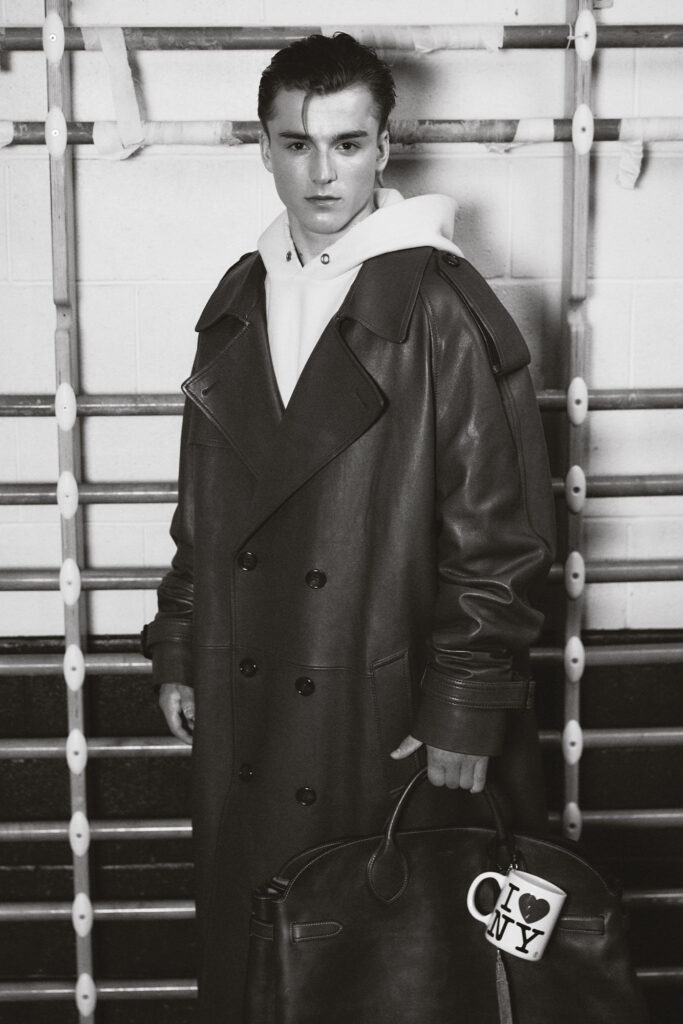

It’s sage advice and, once one retires from their sport, a mantra that will likely lead to a well-adjusted life. Because, even following the greatest of our achievements, our instincts mostly tell us to hold back, to promise the world that we won’t stand in the spotlight for too long. It’s like a little brother, obediently returning the video game controller to an older sibling after a brief chance to play. But, at this summer’s Olympic Games in Paris, 21-year-old gymnast Félix Dolci will lead a new vanguard of athletes onto the world stage, one that is staunchly rejecting the “little brother syndrome” perpetuated by generations past. And, armed with his perfectly manicured blond hair and a dazzlingly white smile, Dolci emanates the sort of unbridled confidence that can only develop after a wealth of early career success.

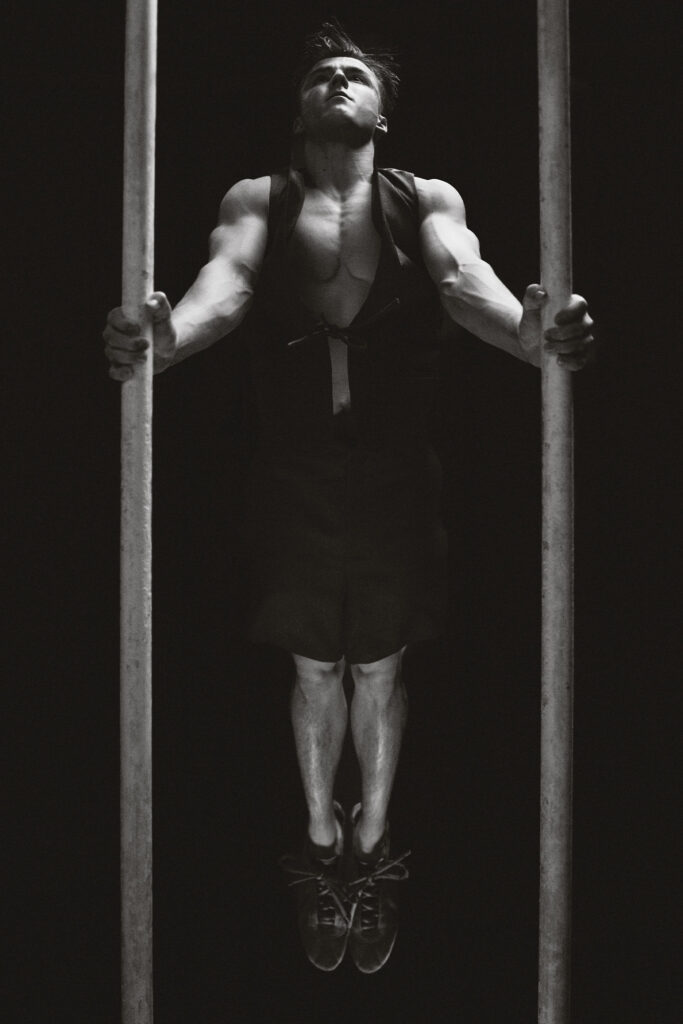

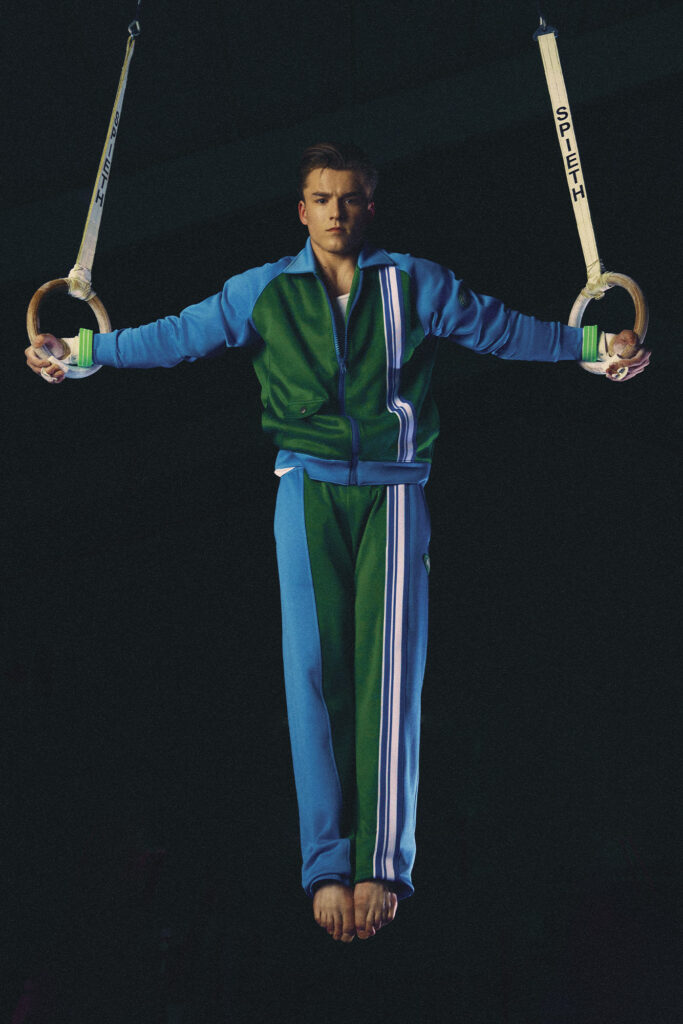

“I was pretty young when I realized that I was exceptionally independent when it came to competition,” says Dolci, recalling his formative experiences with sport. Like most, Dolci played team sports as a child but, by six years old, he grew frustrated when teammates wouldn’t take the competition as seriously as he did. “I basically wanted to have everything on my shoulders. I wanted to control the outcome. So, I started focusing on gymnastics more intensely. I got attached to seeing that progress almost immediately. By 10, I was training over 30 hours per week.”

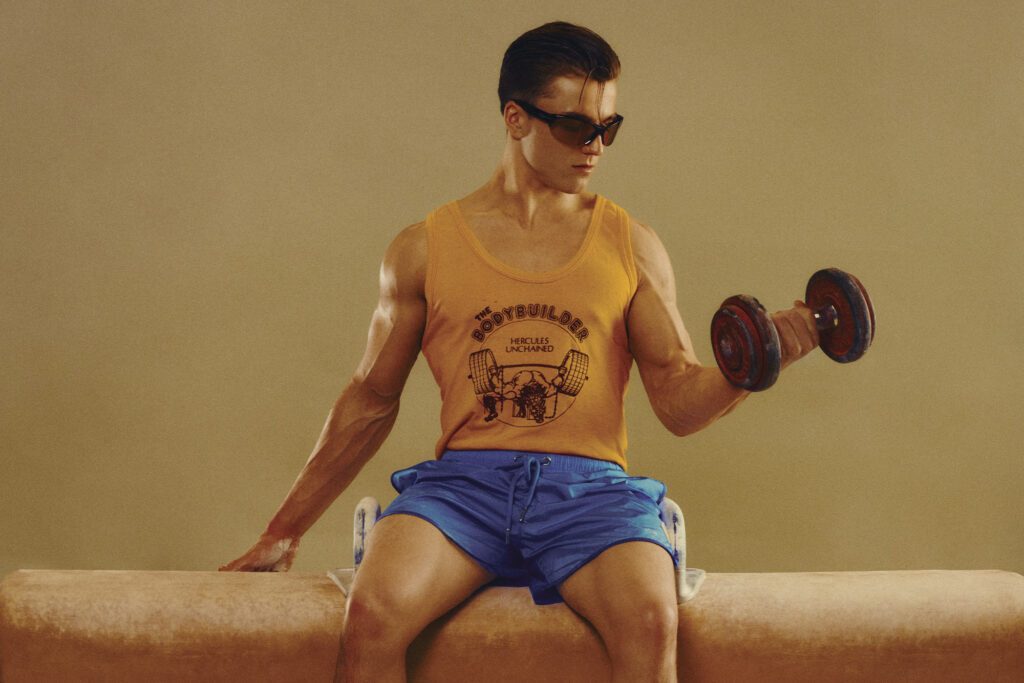

Despite the accolades earned throughout his illustrious junior career, Dolci’s greatest point of personal pride is his insatiable work ethic. In the last year alone, he added five medals (two golds) to his trophy case, won during his debut at the Pan American Games. But it’s not until we discuss his gruelling high school training regimen that a wide smile spreads across his face. Working under coach Adrian Balan — who employs the same militaristic approach shared by most Romanian gymnastics coaches — Dolci found what felt like permission to test his ambition to its highest degree.

“Not everyone wants to get that intense at that age,” he says. “Not everyone wants to take it as far as they can. I wanted to be surrounded by people who wouldn’t limit that. My coach was extremely severe. He still is, but especially when I was younger. I connected with it immediately.”

Ironically, what Dolci discovered through Balan’s rigid discipline was the freedom to work on his craft uninhibited by distractions. Dolci explains that when he or his training partners would fail to put forth what Balan deemed full effort, his remedy was simple.

“He’d kick us out,” he says. “Like, very often. You don’t want to do an extra set? Get out of the gym. You want to apologize for joking around? No, grab your bag. You’re gone. It wasn’t meant to be dramatic or funny. We just aren’t there to waste time. Carelessness is contagious. Laziness is contagious. He doesn’t want one person to expose that to the others.”

At home, Dolci’s father only reinforced his coach’s philosophies. “Pretty early on, he made me a shirt that read, ‘Go hard or go home,’ ” recalls Dolci. “That same mentality was just repeated to me over and over again. I think it’s important that I had that at such a young age because, if it’s not a focus, that’s when everything can go away. Now, it’s just become a part of my DNA.”

To most, maintaining this constant state of discipline may seem extreme, especially when mounted on the shoulders of a 21-year-old. But, as Dolci explains, that’s what the sport demands. Gymnastics is uniquely constructed to find its future stars at a young age. While most sports allow for the late-bloomers and beloved underdogs, gymnastics offers no such grace. Its athletes need to be attuned to the sport from childhood, allowing endurance and power muscles to grow synchronously, and to maintain a necessary strength-to-weight ratio. More importantly, though, as Dolci explains, adopting the sport so early on in life gave him an insatiable appetite for winning.

“If you’re not willing to acknowledge your potential, then how are you going to reach it?”

Félix Dolci

This summer, the Olympics will provide Dolci with his biggest stage yet. He’s only just completed his previous international competition, and is taking minimal downtime before his next block of high-intensity training. I ask if his recent successes have sedated some of the pressure that he puts on himself. His smile disappears. He seems half-confused, half-insulted by the notion.

“Absolutely not,” he says plainly. “After the [Pan American Games], a reporter asked if I was happy with the performance. I thought, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

Across five events, Dolci earned two gold medals, a silver, and two bronzes. But discussing his performance has sparked memories of his perceived missteps during the competition.

“I lost myself two medal opportunities,” he explains. “I came in wanting to medal in all five events, plus the all-around, plus the team medal. That was my goal and I came up short. I think it’s important to admit that. I know my value. There’s no sense in saying, ‘Well, I did well enough.’ I’m happy, sure. But I’m not satisfied. I haven’t proven anything.”

Though two medals shy of perfection, Dolci’s excitement doesn’t dwindle as he explains where he went wrong. In fact, his energy only intensifies as he explains the adjustments he’s made in the months following the Pan American Games.

“I know basically every single gymnast on an international level and I can tell if they’re a real challenger or not,” he says. “I base my potential success and medal chances based on that. When I competed in Canada [as a junior] or when I walked through the hallways at the [Pan American Games], I expected to win. I’m not saying it was guaranteed. Clearly, it wasn’t. But, to this point, I feel like it’s been in my hands. If I execute, I should win. I’ve been competing against myself, to some degree.”

In Paris, the stakes will be greater, as will the competition. “Paris is different. There’s no room for mistakes,” he explains. “If I want a medal, I have to be perfect. It’s another game entirely. I’m looking forward to the challenge.”

Such brazen, unfiltered confidence is startling to hear — particularly when contrasted with his Team Canada teammates. In an era when athletes are increasingly media-trained, general sentiments of “We’re just happy to be here” seem more common than ever and, while inoffensive, they hardly offer genuine insight into an athlete’s psyche.

When asked whether he believes his approach stands in contrast with the typical Canadian sensibility, he laughs before letting out a long, deliberate sigh. “That’s crazy that you’re asking this,” he says. “People never bring it up in interviews. But it drives me crazy. There’s this hyper-sensitivity around recognizing that we all want to be the best. But that’s the arena we’ve entered. Everything is a competition. It’s eat or be eaten. Choose a side. That might sound crazy, but that’s truly how I see it. Recognizing your abilities and your potential is part of that. If you’re not willing to acknowledge your potential, then how are you going to reach it?”

Spoken like a true disciple of his coach’s “work or get out of the gym” mantra, the mere mention of passivity animates Dolci. “Sometimes, I think in Canada, we tell the world, ‘We’re here to have fun,’ ” he says. “And yes, this is a beautiful journey. I’m grateful to compete. But for me, winning is fun. Seeing my teammates succeed is fun. When I feel like I’m going into a battle, that’s when I have fun. That’s where I find joy and peace, almost.”

“Nothing is owed but, man, I love to win. That’s not just in the sport. That’s in life. I won’t apologize for that.”

Félix Dolci

I ask Dolci what results would deliver that joy in Paris. He begins to answer, but then stops himself in a rare moment of self-censorship. Knowing one’s value, it seems, is one thing. But offering a precise medal count on record? Perhaps a step too far.

“I’ll enter Paris as the best version of myself,” he eventually offers. “As long as I’ve done everything possible to put myself in a position to succeed, I’ll be happy, because success isn’t guaranteed. Success isn’t fair. It isn’t owed to you because you think you’ve worked harder than everyone else, especially when the bar is so high. I trained better than I ever had to prepare for Tokyo. Then, the pandemic happened and I couldn’t even compete. Is that fair? I don’t know. But that’s life. The best in the world will be in Paris. Maybe experience wins out. Maybe someone has a better day than me. I can’t control that. I just control the work.”

It’s a strikingly nuanced perspective for a 21-year-old, particularly one with such lofty goals. Still, after a few seconds of silence, Dolci can’t help himself.

“But I want to medal,” he laughs, and once more exhales deeply, as if releasing a sneeze that he’s been holding in. “Nothing is owed but, man, I love to win. That’s not just in the sport. That’s in life. I won’t apologize for that. People might think it’s crazy. But it’s gotten me here. I’m not special. I’m not some ‘Chosen One.’ I wasn’t born with this talent. I didn’t drink a magic potion when I was young. I just love to win. And I hate to lose. It’s as simple as that.”

Photography: Alexis Belhumeur

Grooming: Juliette Morgane (Folio Management)

Special thanks to Laval Excellence.

Styling: Amanda Lee Shirreffs (Folio Management)

Stylist Assistant: Gabriel Dupuis