Christian Allaire Talks New Book, “From the Rez to the Runway: Forging My Path in Fashion”

When I first caught wind of Christian Allaire, I was sitting on the plush couch of a Yorkville office, surrounded by a few racks of not-yet-released clothing. It was October of 2023, and I was there to meet Justin Jacob Louis, founder and creative director of SECTION 35 — one of Canada’s more recognizable streetwear brands. Just a month before, the Nehiyaw (Plains Cree) designer had launched his eponymous high-end label at New York Fashion Week. “I think we did something really special and the most important was that we brought like all our people with us,” Louis said of the show. “And for Christian to write about it right away — it was just so cool; it was great that Vogue was there.”

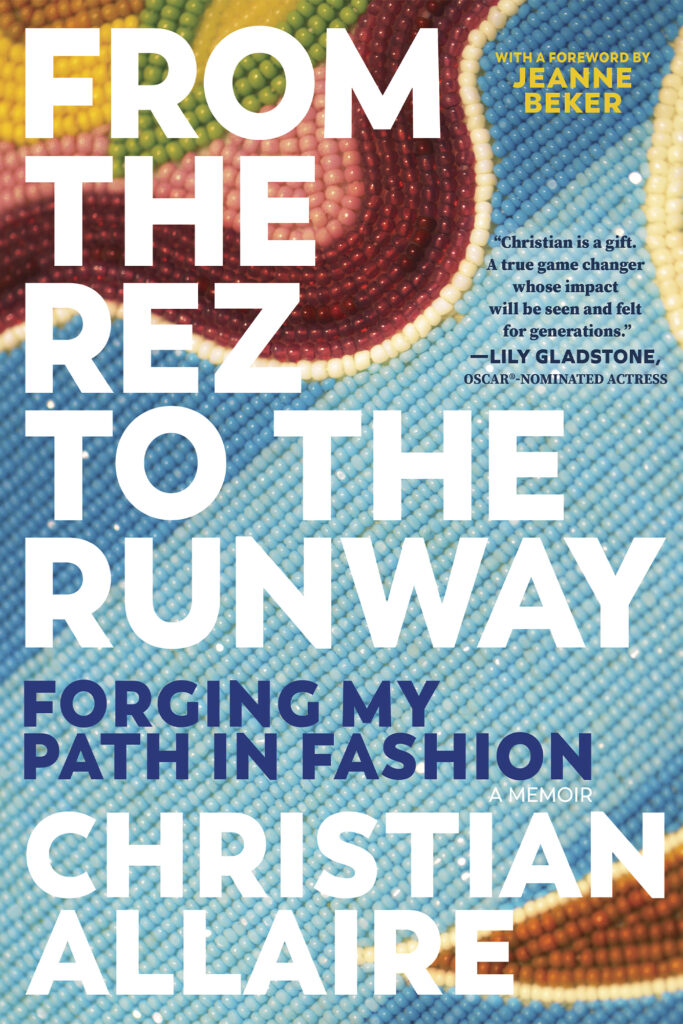

Louis isn’t alone in his sentiments. Allaire has made a career of spotlighting up-and-coming designers, redefining the scope of high fashion to include Indigenous couturiers alongside legacy labels. On the front cover of Allaire’s 2025 memoir, From the Rez to the Runway: Forging My Path in Fashion, you’ll see the title set against a striking, intimate image of detailed beadwork by Jaime Okuma — a Luiseno, Shoshone-Bannock, Wailaki, and Okinawan fashion designer. Calling the Ojibwe writer “a dear friend,” Okuma notes myriad commonalities between Allaire’s story and her own. “The title alone is something that is all too familiar,” Okuma writes in an Instagram caption.

“[Indigenous fashion] made me realize how lucky I am that I come from this culture, and how beautiful and sacred our designs are.”

Christian Allaire

These sentiments seem to resurface in every chapter. Flip open the book, and you’ll find that for Allaire, fashion is much more than clothes — it’s community. Ahead of the book’s release, I spoke with Allaire to learn more about his experience; we covered everything from mainstream representation and Indigenous design to the ever-changing state of fashion journalism. Read our conversation below:

You write that your first experience with loving fashion comes from powwow regalia. Later on, there’s a quote that says: “When you don’t see something represented in the mainstream, you question its validity,” which I thought was really interesting. As you’ve written about Indigenous fashion at Vogue and throughout your career, how has your perspective on mainstream representation changed?

Yeah, that was a big… I don’t know, discovery. When I was writing this, I reflected on my early years of loving fashion. Obviously, I was obsessed with Vogue, Fashion Television — all these mainstream outlets for fashion — and I never saw my culture represented. I didn’t really think a lot about it, at the time. I just discounted it as like, ‘Oh, well then, that must mean, like, our cultural clothing is not fashion. It must not be worthy.’ So, for the longest time, yeah — I totally shunned our own cultural designs because I just felt like they weren’t beautiful.

“Fashion makes it very easy for you to feel like you’re not good enough, not stylish enough, not cool enough — at every party or show you go to, there’s a million more beautiful, more cool people — but I guess I just allowed myself to play dumb, and to throw myself into rooms that I probably shouldn’t have been in.”

Christian Allaire

It wasn’t until later in my career — when I started writing about Indigenous fashion again, and meeting designers who were taking contemporary approaches — that I started to realize the beauty of it. It took me writing about it for a few years to realize, ‘Okay, just because it hasn’t been in the mainstream doesn’t mean it’s not actually beautiful.’ I don’t know why it took me so long to realize that, but it wasn’t until I was actually meeting designers and hearing from them firsthand about what inspires their work. It really shocked me. I was like, ‘This is actually couture. This is actually better than what I’m seeing on the runways in Paris, it’s just that nobody’s writing about it.’

The most fun thing about taking on this niche in fashion — writing about Indigenous designers — is that, on a personal note, it made me realize how lucky I am that I come from this culture, and how beautiful and sacred our designs are. I mean, it took me 30 years to realize that, but better later than never!

Starting out in publishing, I think it’s during your time at Flare, you talk about your first couple pieces being “almost entirely rewritten” until you get the hang of the magazine speak. I thought about that in relation to what you’ve said about fashion; how you give yourself the agency to recognize, ‘Okay, this is couture and this is really relevant to the fashion scene, and we should be covering this.’ Did those two journeys dovetail for you?

Definitely. I think about my early college years, when I was starting to pitch magazines and stuff, and I was interested in Indigenous design. It wasn’t that I wasn’t pitching it — I didn’t know if people were interested, but I was pitching it — but nobody wanted that. Like, I was told on multiple occasions ‘These designers are not up to par with what we’re looking for.’ So, I was going through that at the same time as I was doubting the validity of my culture — those two things happened at the same time. If the industry is not ready for it, then people won’t be ready for it on a personal note, too.

“We all need to slow down, and we could actually learn a lot from Indigenous designers because their work is very sustainably minded, it’s very culturally minded. It’s just all the good things that I think fashion should be.”

Christian Allaire

The more I pitch stories, the more people have been open to them and realize the beauty of them. That also, on a personal note, made me really value it more, too. But you need the mainstream approval, I guess — which is a sad state of fashion — for these stories to be shared and told.

A common criticism of the fashion industry is its emphasis on consumerism and and consumption. As I was reading your work, whether you’re talking about family members’ regalia or the fashion shows you had as a kid, I noticed the focus on creativity, on making things. You’re pushing that conversation in fashion away from consumption and towards creation. Was that dichotomy something you thought about while writing?

Yeah. I mean, it’s funny. Indigenous design, at its core, it’s really hard to have a place in fashion because it’s so opposite to what is happening. Like, think of mainstream luxury brands: they’re churning out multiple collections a year — fall, pre-fall, spring — the rate at which designers are consuming is so fast, and everything in Indigenous design is extremely slow. Some of my favourite artists will take a full year just to make one piece. It’s done by hand, and it’s very thought-out and very intentional. Like, the core of the Indigenous values doesn’t really fit into a fast-paced, high-fashion business model.

So, they are at odds with each other, but I don’t think that means they can’t exist with each other. I think there needs to be a change in the industry to allow designers to produce at a slower rate. I don’t think it’s sustainable for anyone, how quick it’s going right now. That just points to a larger conversation; we all need to slow down, and we could actually learn a lot from Indigenous designers because their work is very sustainably minded, it’s very culturally minded. It’s just all the good things that I think fashion should be.

You’ve written a lot about the fashion side of your career; very quickly, you knew that you wanted to pursue fashion and join this world. When it comes to writing a memoir, when did those thoughts first emerge — is it a newer dream of yours?

Yeah, it’s definitely newer. I have not, traditionally, written about myself. I much prefer to write about other people — I think that’s way more interesting. So, honestly, this book was not my idea. I was approached to do it. I would never sell a memoir myself.

When they first approached me, I didn’t think my story was interesting. Honestly, I was like, ‘I don’t really have a story to tell.’ But then, when they’re like, ‘That’s a lie,’ I started thinking about it, and I was like, ‘Okay, it is a very unusual arc, for a little res kid to end up working the biggest fashion magazine in the world — okay, I get it.’

This more personal angle of writing is definitely new for me. I honestly don’t know if I’ll keep doing it. I think it was a fun stretch for me, and a fun challenge to use my brain in a different way, but to be blunt, I’d much rather interview other folks.

Sometimes it’s easier to get to the core of of a topic when you aren’t the topic in question?

Yeah, it’s hard to be objective about yourself. Obviously when you’re profiling someone or writing about someone, you try to be objective. That was impossible to do with my story, so it was a weird process but a fun one, and definitely an enlightening one.

As you write about these chapters in your life, you seem to have so much determination. First it’s being in Toronto, being at TMU. Then, right away, you’re ready to jump into New York to work for Interview. Of course, you talk about feeling unprepared or having imposter syndrome, but — at least for me, as a reader — I felt like you didn’t act that way: even if you were feeling that, it didn’t hold you back. What was the process to overcome those feelings of inadequacy or self-doubt?

I guess you’re right. Throughout my life journey, I’ve really just been naive and just thrown myself into things. Fashion makes it very easy for you to feel like you’re not good enough, not stylish enough, not cool enough — at every party or show you go to, there’s a million more beautiful, more cool people — but I guess I just allowed myself to play dumb, and to throw myself into rooms that I probably shouldn’t have been in.

I get asked a lot about my main advice for youth, and I think my main advice would be exactly that: to just fake it till you make it. That’s really what I would attribute where I’ve gotten to — just being delusional and thinking, ‘One day, I’m gonna get there.’

“It’s really important for anyone who wants to be in fashion journalism to treat it seriously, and to realize it is real journalism.”

Christian Allaire

I think it’s important to be a little delusional, honestly. I know that sounds crazy, but I would not be working here right now if I wasn’t a little delusional. Getting to Toronto, forcing my parents to get me there, somehow, took a lot of delusion. Then, convincing them to let me move to New York, and finding a way to get there, took delusion. So, I don’t know, I think it’s an important lesson. I mean, you have to be a little realistic, and you have to have a plan to achieve your goals, but I think you can also like allow yourself to dream and try things. Even if you fail — like, I failed a lot — but with failure also comes success.

When you write about your first courses at TMU, you say that a lot of people are really interested in being a ‘serious journalist’ whereas you write ‘I just wanted to write about clothes.’ How did your perspective on fashion journalism versus other forms of journalism evolve after years of working in this space?

Yeah, it’s funny. When I first was at college, I was taking all of these political journalism courses where I had to go to City Hall and report on a crime investigation. I was doing all these things and I was like, ‘This is not what I want to do at all. Why am I doing this?’ I had such an attitude about it.

But later, I realized that that was really important. All the skills you use in hardcore reporting also apply to the fashion world. Like, I think about what I do now — when a celebrity hits a red carpet, or a new couple is dating, or a runway show has just happened — we have to be quick: we have to report, we have to get the quote. It’s the same treatment as you would give to a president announcing he’s stepping down or something. You still have to be very quick, very research-based, very on the pulse.

At first I was like, ‘I just want to write about pretty clothes, why am I learning all these things?’ But it’s really important for anyone who wants to be in fashion journalism to treat it seriously, and to realize it is real journalism. I think bad fashion writing is someone who doesn’t do reporting and researching and interviewing. It took me a while to learn that lesson — probably my whole time in college, honestly — but at the very end, I was like, ‘Oh, this was all worth it.’

You also talk this idea of fashion as a vehicle to highlight Indigenous culture through different Indigenous designers. I wonder if that speaks to someone who wouldn’t be familiar with fashion journalism, or isn’t taking it seriously; hearing that aspect of the story helps translate the depth of this work.

Yeah, because with any form of journalism, you need an angle, or a voice, that sets you apart from everyone. You really need to come on the scene with some sort of point of view. In fashion journalism, I think that’s equally important. Like, 10,000 people are doing trend reports — you have to bring something else to the table.

When I started thinking about that after I graduated, I was like: ‘What am I gonna bring to this industry that’s valuable or interesting?’ And, when I quickly realized that nobody was writing about Indigenous fashion across North America (which is kind of still the case, sadly), I was like, ‘Well, I guess it’s gonna be my niche.’ It kind of came from a selfish place — just because I was interested in that and I was familiar with that — but I quickly realized there was a huge audience for it because nobody was writing about it. It felt very new and foreign to a lot of readers. I think you just have to find your voice and find your interest, and that is what’s gonna be successful for you as like writer.

Fashion journalism, like all forms of journalism, has undergone this huge transformation in the last decade, two decades. You started out with the debut of web journalism, when people were first taking digital seriously. Now it’s the same thing with social media journalism and video production. How has the changing industry affected your work, and what are some changes or things that excite you about this moment in journalism?

It’s changed so much. I think about my time at TMU, and our digital journalism course was introducing concepts like Twitter. It was still just starting — and that makes me feel really old, because now journalism is like… you have to be on all these platforms.

When I do a story now, it’s not just for vogue.com. I have to think about what we’re gonna use for Instagram, so I’m like ‘What photos are we gonna use there? Is it gonna be a different video from what I used in the story?’ Then I have to think about TikTok, like ‘Maybe I’ll hop on into a TikTok about the story I just wrote.’ So, you’re kind of doing like three times the content now, and the way you do it on one platform will be totally different from the other.

“There’s been shows like Rez Dogs and things like Indigenous Fashion Arts in Toronto. All these things are working in tandem to boost a collective interest in Indigenous culture.”

Christian Allaire

It sounds like it’s a lot more work and more daunting — and sometimes it is! — but I actually think it’s a lot more fun and dynamic, because you can report on one story but reach seven different audiences in seven different ways. I think that’s really cool. You really have to embrace all the different types of storytelling. We’re so, like, ADHD when it comes to content. I feel like everyone is these days. You have to find different ways that it’ll stick and get the word out there. When I go to something like Indigenous Fashion Week, I’m not just like doing a round up for the website. I’m also taking videos for Insta, interviewing people for TikTok. It’s a whole thing, and I think it’s really fun.

I feel like one of the more positive aspects about social media is the way it has democratized the flow of information. It’s easier to become one of those authoritative, respected voices by creating quality content.

That’s so true too. I think about the first stories I did about Indigenous fashion. If they hadn’t blown up on social media, gotten clicks and had people sharing it, I probably wouldn’t be allowed to make it my thing, you know what I mean? That’s part of journalism too: you have to get the engagement from readers and if you don’t, then you might not be able to do those kinds of stories. The power of social media and community rallying behind this type of content is why I’m able to be here.

That’s an interesting point of view about engagement — not just in the sense of likes and comments — but also what people are saying. From your early days reporting on Indigenous fashion up to now, how has the audience reception been for you? Have you noticed that people are more receptive now that they’re aware of different Indigenous designers?

At the beginning stages, I was just getting a lot of feedback from designers being like, ‘We never thought we could be in Vogue!’ or ‘We never thought we would see the day that Indigenous fashion is covered in such a big way.’

I still definitely get those reactions from people, but now, what I’m really loving is that I’ll get emails from total strangers — like non-Indigenous even — and they’ll just say: ‘Thank you for writing this. I have no idea this culture existed, or this tribe did this form of artwork, and you really taught me something.’ That, to me, really makes it worthwhile, because obviously you’re trying to educate people and just introduce them to a whole new form of design.

So I feel like, yeah — the public appreciation and interest has grown a lot, which is really cool to see. Obviously, that’s not just because of me. There’s been shows like Rez Dogs and things like Indigenous Fashion Arts in Toronto. All these things are working in tandem to boost a collective interest in Indigenous culture. I think that’s really cool to see because for the longest time, it was not like that.

On that note, who are some of your favourite Indigenous designers that you’re wearing now?

There’s so many! I love a shoutout moment. Let’s see… Jamie Okuma is my all-time favourite, I think her work is amazing. Elias Jade Not Afraid is a beadwork artist, Keri Ataumbi from Ataumbi Metals is an amazing jeweller. Tania Larsson from Yellowknife is amazing. I think of brands like Section 35, which is more of a streetwear brand, is really cool; same with mobilize.

“If you’re buying directly from an Indigenous artist — who you know is Indigenous, that’s important to check — you’re supporting them. That’s authentic appreciation, you’re supporting a business.”

Christian Allaire

That’s the cool thing. Now, in basically any category, you can find an Indigenous label: there’s swimwear, there’s streetwear, there’s formalwear. For the longest time, there was this excuse that Native design is just one very-specific thing. Now, it’s in virtually every sector of the industry. So, you can support it if you want to — it’s just that people don’t look for it. But that’s the most exciting thing to me: any product that you can think of, you can find it Indigenous-made, which is cool.

Another response I’ve seen is that non-Indigenous people sometimes hesitate to embrace Indigenous fashion out of concern that they might wear it in a disrespectful or uninformed way. But as we highlight more Indigenous designers — along with jewellers, accessories, and streetwear — we’re seeing that it’s something everyone can embrace.

Yeah, I think people are still a little… the line between like appreciation and appropriation, people are still scared of crossing in the wrong way. But I always say: if you’re buying directly from an Indigenous artist — who you know is Indigenous, that’s important to check — you’re supporting them. That’s authentic appreciation, you’re supporting a business. They would never sell something culturally insensitive; they would never sell that for the public.

So, 9.9 times out of 10: if it’s for sale, you’re good. You’re doing the right thing, and it’s better to do that than to buy a replica from a non-Indigenous brand. I really encourage people, if they want support Indigenous artists or do it the right way, to buy from them directly — and yeah, you can rock it. They want you to buy it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.