Long before it was occupied by the ever-expanding checklist I keep to ensure the kitchen at STK Toronto operates like a Rolls Royce Merlin engine, the question on my mind was much more simple: is the motor on the Vespa hot, or cold? The answer would determine how my 16-hour shift at London’s most popular restaurant would be.

Early in my career I staged at the Capital Restaurant at the Capital Hotel, in Knightsbridge. It was helmed by the city’s golden chef, Eric Chavot, proud owner of two Michelin stars and incredible acclaim — and a lipstick red scooter. I, on the other hand, working on just three hours sleep thanks to a busy shift the night before, pondered today’s mise en place while transferring from one cramped double decker bus to another to be at work before the sun rose. If the Vespa’s engine was warm — or even better, hot — it meant that Chef Chavot had just arrived. This was good. If the engine was cold, it meant he had been there for hours, long before me. I would marvel at how a chef of his stature could leave the restaurant at 2 am and return at 6 am, night after night. He’d work alone – nothing was beneath him, even scrubbing floors with a grout brush — waiting for his disciples, wondering why my generation was so soft. Working for Chef Chavot required intestinal fortitude and an exceptional desire for perfection.

Over the past decade, how and what guests eat, and the way restaurant kitchens run, has changed. I wondered if that constant striving for perfection had, too. Food TV has offered diners entry into a once-unfamiliar world. Time is everyone’s challenge. Now, you sit down to dinner and make menu choices by looking at your phone, taking subjective suggestions from people you don’t know instead of listening to the server. The clock isn’t going to turn back, so I wanted to ask my mentor what his thoughts are on cooking with snowflakes, how technology has changed the dining experience, and the future of fine restaurants.

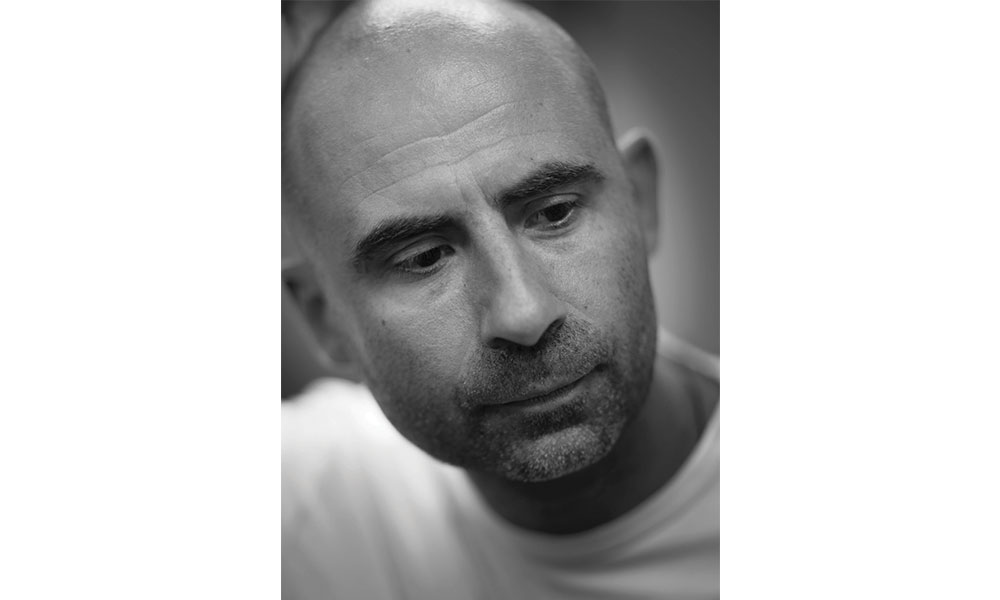

Chef Eric Chavot

Chef Eric Chavot

Where are you cooking these days?

I’m tired of how things have changed in London. It’s too expensive and I want a fresh start, so I’m opening a 75-seat restaurant in Hampton, with only 10 of us in the kitchen.

Are you ever going to slow down?

Never. I get more done now by taking a step back, but I’ll never slow down. My wife wants me to retire in five years, but that’s not going to happen.

You’re making us all look bad! You’re supposed to let the generations you’ve trained start to take over — do you think that’s something you’ll see happening soon? Or is there is too much to learn before you hand it over?

Only a small handful will take over. Guys like you who did it for real. We used to work for quality — that was the name of the game. We worked for ourselves, not for Michelin, and for that, they rewarded us.

When working with young cooks, what’s the most obvious difference between now, and, say, 10 years ago?

The desire to do it, and the goals they want to achieve. Before, they wanted to work with — and learn from — someone who was respected for all the right reasons. Now, it’s about building their own name. But if you can’t do the work, how you can claim to be a chef? There’s a culture to find “the next chef,” so someone who’s young and not ready suddenly gets thrown into the limelight, and is told he’s the next best thing. For six months, he feels like a rock star, and then — bam! — it’s over. They’ve moved on to “the next chef.” You don’t come back from that; it’s ruining young chefs. It should be about quality, and who’s doing something unique, not what’s trendy. Chefs used to look at cooking as a craft. You had to learn it.

What do today’s diners want?

Diners today are far more demanding than they used to be. Technology affects the kitchen and the restaurant — and not necessarily in a good way. Fifteen years ago, people came for the food, and for a dining experience. Now, people are not paying enough attention to each other. At Brasserie Chavot, I used to have an open kitchen, so I was able to watch and interact with the guest. If a husband and wife were just sitting there, I would send over champagne, and sit next to them and ask them, “Is your husband really that boring?” I was trying to get people talking. But everyone’s on their phones, and not paying attention to the details around them: the server, the table, the glassware, the chef, the food, each other. It’s sad.

Do you think fine dining will make a return?

It’ll come back, like flared jeans from the ’70s. It’s all about quality. Chefs who traditionally had stars have all changed what they are doing: the white tablecloth is gone, and the food is simpler. To do it as an individual will be almost impossible, though, so you’ll have to join a larger group to help you out. With the cost of running a restaurant, you need help. But young people don’t want to do it anymore — that’s why so many restaurants like Robuchon and El Bulli closed, or changed what they do. The only places where this is still going on are places that have money, like Dubai.

Do you still ride the Vespa?

No, I’ve upgraded, but I don’t have the heart to sell it. It’s my most cherished possession. It sits in

my garage now.